Australian Journey Episode 07: The Stolen Generations

WARNING: this video contains some potentially distressing content.

Learn about the history of forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families in Australia.

View transcript

+ -SUSAN CARLAND: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this series may contain images, voices or names of deceased persons.

BRUCE SCATES: This episode, The Stolen Generations, is part of the series that deals with people. It begins in Canberra, moves across to Melbourne, and ends in a remote Aboriginal settlement in Western Australia. We examine the confused racial thinking behind what many have described as Australia’s own attempt at genocide, and we celebrate the survival of Indigenous people.

SUSAN CARLAND: John was one of thousands of Aboriginal children who grew up never knowing his mother. First, he was placed in an orphanage and told by the missionaries that he had to be white. Then they sent John to Kinchela, a Boys’ Home on the Macleay River, hundreds of miles from his home.

BRUCE SCATES: John was just 10 years of age when an iron gate clanged shut behind him. That same iron gate is the object of this episode and 30 years on John remembered every moment vividly.

[reading from oral history testimony]

‘They took your bag from you, everything you owned, and threw it on a fire. Then they shaved your hair, they stripped you down, they made you dress in clothes stamped with a number. They never called you by your name, they called you by your number. Kinchela was a place they treated you like animals.’

SUSAN CARLAND: John remained at Kinchela for all that was left of his childhood and in a way his childhood was taken from him.

BRUCE SCATES: [reading] ‘All you did was work, work, work. We never went into the town – the Boys’ Home was just a prison.’

SUSAN CARLAND: Kinchela was a place of physical and emotional maltreatment. White managers and white staff controlled the lives of Aboriginal children. Sometimes they even sexually abused them. And for the most part the authorities turned a blind eye – at Kinchela, at Cootamundra Girls’ Home, at institutions for the so-called ‘half-caste’ children right across the country.

BRUCE SCATES: John was one of the Stolen Generations – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children taken from their families, fostered out to white homes, imprisoned in white institutions. His testimony is recorded in this report, a National Inquiry into the Stolen Generations, and their pain, their hurt, the great wrong that was done at Kinchela and at a hundred places like it, is the subject of this episode.

SUSAN CARLAND: How and why were the children taken? The answer lies in a fundamental inequality enshrined in the Constitution of the Commonwealth.

In the early 20th century, Australia’s first Parliament sat here in Melbourne, and many government offices, like the Old Treasury Buildings, became a concern of the Commonwealth. Aboriginal people were denied the basic rights of citizenship: they could not vote; they had no say at all over the laws that governed their lives; indeed, the early Australian Commonwealth abdicated all responsibility for what was commonly called Native Affairs. Indigenous Australians were not even counted in the census. The nation we created in 1901 defined itself as white.

But the laws that administered Aboriginal Australia, the rations and the rules, they were made at state rather than national level. Victoria’s Protection Board sat here, in this beautiful room. Each state set up so-called Protection Boards to ‘manage the natives’, and it was here that decisions were made that changed the fate of thousands.

BRUCE SCATES: ‘Protection’, we called it, but it really involved a raft of repressive legislation. Susan and I have been charting the way that legislation evolved in this dusty collection of old parliamentary papers. All these Acts – Western Australia, South Australia, Queensland and so on – have a number of things in common. They decreed where Aboriginal people would live; they displaced them from their traditional lands; and they drove them into missions and reserves managed by white authorities. Protection Boards determined where Aboriginal people would work and who could employ them and it’s here we see the first of the Stolen Generations, from these earliest debates in the Victorian Parliament. Protection Acts progressively assumed more and more control over Aboriginal children.

SUSAN CARLAND: The white state decided where and how children like John would grow up, not their Aboriginal or, in official parlance ‘part-Aboriginal’ parents. That very term, ‘part-Aboriginal’, alerts us to the confused racial ideologies that drove much official thinking.

Today in Australia, Aboriginality is defined by Aboriginal people themselves. Under the regime of ‘Protection’, that choice was made for them. This was a biological as much as a cultural criterion.

The black population was defined as ‘full-blood’, ‘half caste’ and so on. This 1936 Act from Western Australia defines a so-called ‘quadroon’, a person of only one-fourth ‘Aboriginal blood.’

BRUCE SCATES: Racial theorists from the 19th century and right into the 20th believed that so-called ‘black stock’ would weaken over time. Each generation, they said, would become successively more European until eventually they’d be ‘absorbed’ altogether.

Taking Aboriginal children from their families, encouraging the lightest to marry into white communities, was the way, it was thought, to blend together white and black and ‘breed the colour out of them’.

Assimilation, as eugenicists came to call it, was a program of social and biological engineering. Like earlier protectionist policies, assimilation involved the isolation, the classification, the control, of Australia’s so-called ‘natives’; the forced removal of children; a sustained attack on any cultural practice deemed Aboriginal. White administrators spoke of ‘tribalised’ and ‘de-tribalised blacks’, the ‘semi-civilised’ and the ‘savage’. In the Social Darwinist discourse of the time, Aboriginal people were destined to ‘die out’ and the oldest civilisation in the world dismissed as ‘simple’ and ‘primitive’.

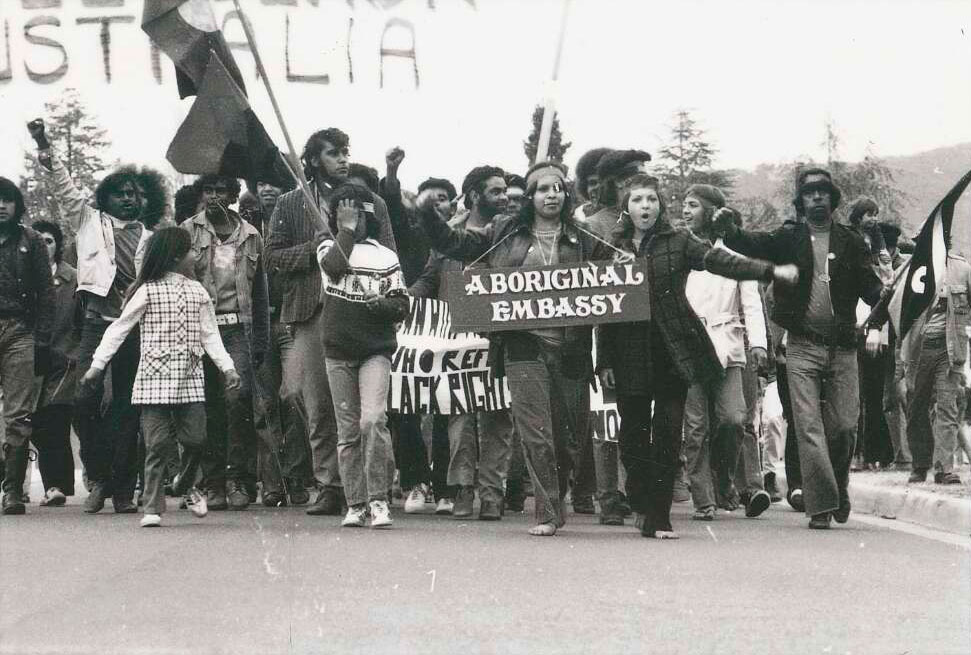

SUSAN CARLAND: Today we fly the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags, but back in the 1920s Australia had embarked on a social experiment many would define today as genocide. And where better to see those policies at work then on the very last frontier of European settlement, Western Australia.

BRUCE SCATES: I’m walking along the banks of the Moore River, near Mogumber, in Western Australia. It’s summer and yesterday – yesterday the temperature soared to over a hundred degrees Fahrenheit. These brackish waters behind me flow right through the heart of the Moore River Native Settlement. From 1917 to 1951, thousands of Aboriginal people were sent to this reserve. They were taken, taken from their traditional lands and communities right across the length and breadth of WA.

Aboriginal people were isolated on the reserve, and within the settlement itself, a strict geography of control served to isolate them from one another. On the riverbank, the so called ‘black camp’ was set up. It was just a makeshift assembly of tents and tin sheeting. There was no sanitation, no heating, no electricity. This was a place where the ‘least Europeanised’ of the so-called ‘natives’ would live. The white managers of this mission believed that ‘black-blood’ and ‘black ways’ set them apart from the Settlement’s civilising mission.

SUSAN CARLAND: The youngest of the Settlement’s inmates, plus those considered most receptive to white education lived here, in a place called ‘the compound’. It’s on the high ground, about two kilometres from the river camp. Here too conditions were primitive. This school hall behind me doubled as a church, a concert hall, and even a hospital.

There’s little left of the compound today, just the remains of old Nissen huts and rusting agricultural machinery. Boys lived in one dormitory, girls in another. In the bakehouse, kitchen and laundry, girls learnt the domestic skills needed to work in white households. Boys were given equally menial tasks on the settlement’s farm, training for future lives as labourers.

For all the talk of assimilation into white society, or rescuing children from lives of neglect, the opportunities offered by Moore River were harshly limited. This was a place of overcrowding, hunger and disease. In the classroom, kitchen, church and paddock, ‘part-Aboriginal’ children were taught the white man’s virtues of work, discipline and obedience. And around 200 children under the age of 5 would die here.

BRUCE SCATES: As a working farm, Moore River quickly proved a failure. The soil here, really, it’s not much better than sand and, once this land had been cleared, it struggled to support an orchard or a vegetable garden.

Many of the white mangers here were inept and some of them – some of them were very, very cruel. Now it’s true that in the early 20th century, the confinement and beating of children, white and black, wasn’t uncommon. But surely nothing, nothing can excuse what happened behind these walls. The brutality of Moore River shocked even the white authorities.

SUSAN CARLAND: At Moore River, and a hundred places like it, the authorities placed a strict ban on any practise deemed Aboriginal. ‘Speaking the language’, as Aboriginal people called it, was forbidden. English, the so-called civilised tongue, was all that was allowed here. Other overt traditional practises, such as dances, song and ceremony, were viewed with hostility and suspicion. Education and the church could be a source of strength and solace for Aboriginal people, but on settlements like this it could also be an instrument of dispossession.

At Moore River, Aboriginal children were told to live and think like whites; learn the virtues of industry and frugality; adopt the trappings of respectability, but never act above their station. So-called ‘uppity Blacks’ were what the managers couldn’t stand, Aboriginal people who assumed equality with white men.

BRUCE SCATES: And the powers at the Department’s disposal, they were formidable. For the best part of three decades, AO Neville was the Chief Protector of Aborigines here in Western Australia.

Under the Act, he assumed legal custody of all ‘native’ children. He could order their removal from their families. He selected the ‘lightest and the best-behaved’ for work in white households. The treatment of adults was equally paternalistic. Neville alone could decide who could marry and to whom. Aboriginal people could not leave the reserve without the manager’s permission. Their rations could be withheld. They were not permitted to drink alcohol or to vote. The same police charged with their removal as children were appointed as their ‘protectors’.

The department also regulated employment. Aboriginal men were farmed out, farmed out as labourers. They were put to work, clearing fields like this or harvesting timber. Those men were paid well below the going rate for whites and often those wages were withheld – they were placed in trusts they never saw, controlled by the Department.

SUSAN CARLAND: You could escape life ‘Under the Act’, as Aboriginal people called it. Exemption certificates were granted to Aboriginal people who proved themselves law-abiding and industrious; who achieved acceptance in wider white society; who agreed not to consort with other Aboriginal people. But the privileges of white citizenship were only extended to those prepared to repudiate their Aboriginality. Most Indigenous people held the exemption clauses in contempt – the ‘Dog License’, they called it.

BRUCE SCATES: But the control that was sought by men like Neville, it was never total, and it was never uncontested. At Moore River, and Reserves like it all across the state, Aboriginal people still spoke the language; they absconded and disobeyed; they kept alive the old ways; they performed the old ceremonies; and they resisted, time and time again, the attempt by whites to destroy their culture, manage their lives and take away their children.

Men like Neville had hoped that segregating and controlling Aboriginal people would achieve what he saw as a ‘civilising mission’. It was supposed to destroy the physical and the emotional fabric of their society.

But settlements like this also threw Aboriginal people together and fostered a sense of enduring common identity. So, at Moore River today, Aboriginal communities from all across WA are rebuilding their lives. They are reclaiming the years that were stolen from them.

[TEXT] [music]

In 1997, a government-commissioned inquiry recommended compensation and an unreserved apology to the ‘Stolen Generations’.

Western Australia – the state responsible for Moore River – was the first state to say ‘Sorry’.

By 2001, all state and territory governments had followed.

When a conservative Federal Government refused to issue a formal apology, a ‘Sorry Movement’ spread across the country.

Communities, white and black, large and small, called on Prime Minister Howard to apologise.

In 2007 the Australian Government finally reached bi-partisan consensus.

A new Prime Minister – Kevin Rudd – issued a formal apology on behalf of the parliament and the nation.

The apology was broadcast live and witnessed by millions.

It is screened continuously in the Indigenous galleries of the National Museum of Australia.

The Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation was established in 2001. It works to reconnect members of the Stolen Generations.]

PRIME MINISTER KEVIN RUDD: ‘We apologise especially for the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, their communities and their country. For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry. To the mothers and the fathers, the brothers and the sisters, for the breaking up of families and communities, we say sorry. And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry.’

[music]

BRUCE SCATES: If you’d like to learn more about the issues raised in this episode, why not catch Susan Carland: In Conversation. This time, Susan is talking to historian, Peter Read, on the banks of the Yarra in Melbourne.

Activities

1. At the beginning of the video we hear about John’s experience. What object is used to illustrate his story?

2. How do the presenters answer the question: ‘How and why were the children taken?’

3. Who was A O Neville? How do the presenters use his story to shed further light on what happened to the Stolen Generations?