‘It’s our place, our land’

1985: Australian government returns Uluru to its traditional owners

‘It’s our place, our land’

1985: Australian government returns Uluru to its traditional owners

In a snapshot

Uluru is one of Australia’s most important icons. It is also a sacred site for the local First Nations people, the Anangu. The Anangu lobbied for decades for the rights to their traditional lands. In October 1985, the Hawke government handed back the title deeds for the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park to the Anangu. Today Uluru and the park are jointly managed by the Anangu and the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Can you find out?

Can you find out?

1. Who are the traditional owners of Uluru?

2. Who was the first known European to visit Uluru? What did he name it?

3. What have been some of the problems associated with climbing Uluru?

Why is Uluru so important to First Nations people?

For the Anangu, Uluru has been there forever and is a deeply sacred place. The Anangu believe the landscape was created by ancient beings and that they are direct descendants of those beings. They believe they are responsible for protecting and managing the lands around Uluru and Kata Tjuta, a rock formation nearby (which is sometimes known as Mount Olga or the Olgas).

When did Europeans first visit Uluru?

The first European we know visited and climbed Uluru was explorer William Gosse. In 1873 he named it Ayers Rock after Sir Henry Ayers, Chief Secretary of South Australia.

In the 1890s a scientific team researched the geology, mineral resources, flora, fauna and First Nations culture of the area. They decided it was unsuitable for farming. Few non-Indigenous people visited the area until the 1940s.

The first road to Uluru was not built until 1948. It brought miners and tourists, and the Ayers Rock National Park was declared in 1950. Tourism gradually grew, and a new airstrip was built to allow visitors to fly in.

Kata Tjuta was added to the park to create the Ayers Rock-Mount Olga National Park (later known as the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park) in 1958. The park was managed by the Northern Territory Reserves Board and the Anangu were discouraged from visiting. However many still travelled across their traditional lands to hunt, gather food, visit relatives and participate in ceremonies.

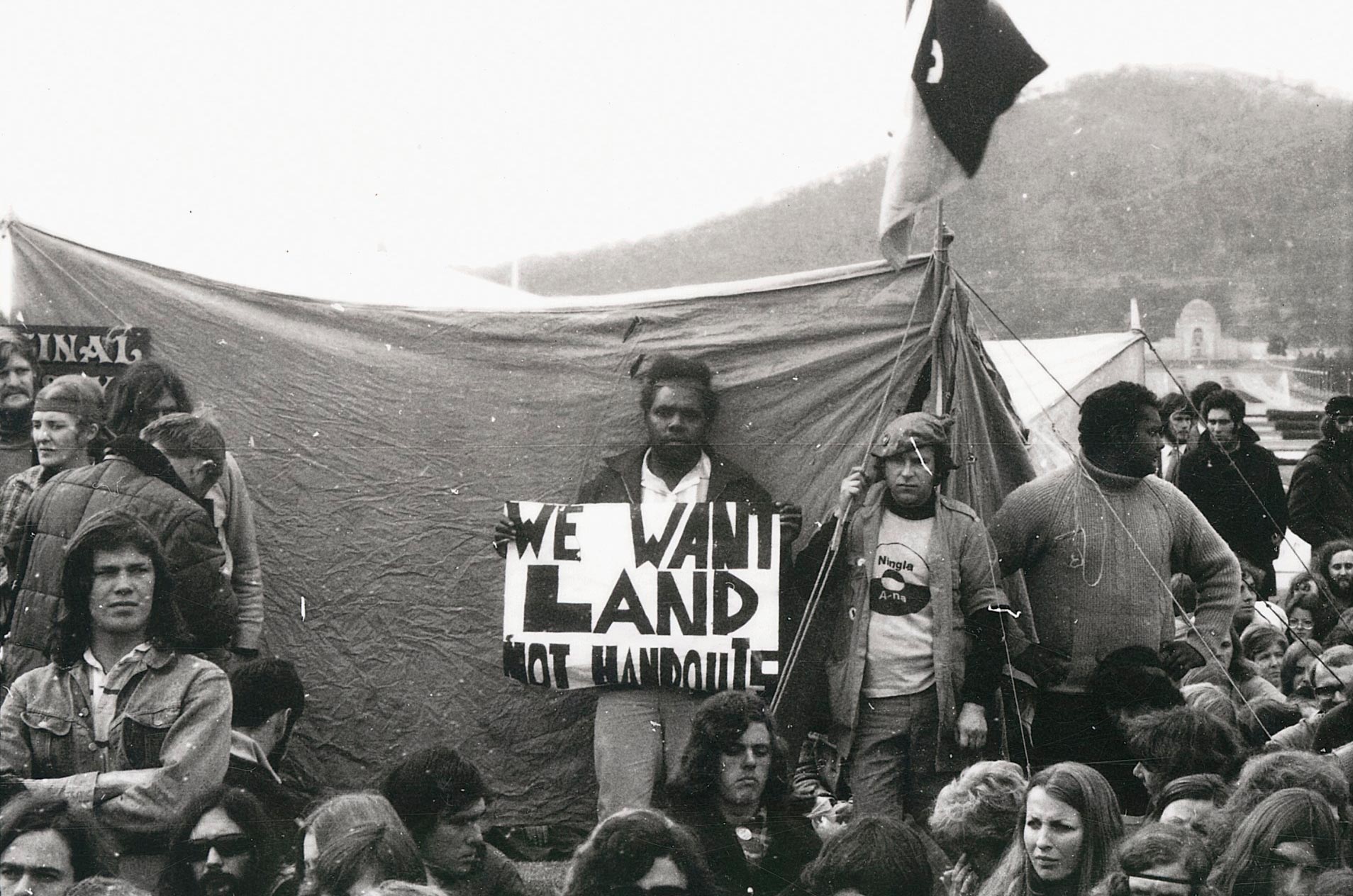

When did the Anangu start lobbying for their land rights?

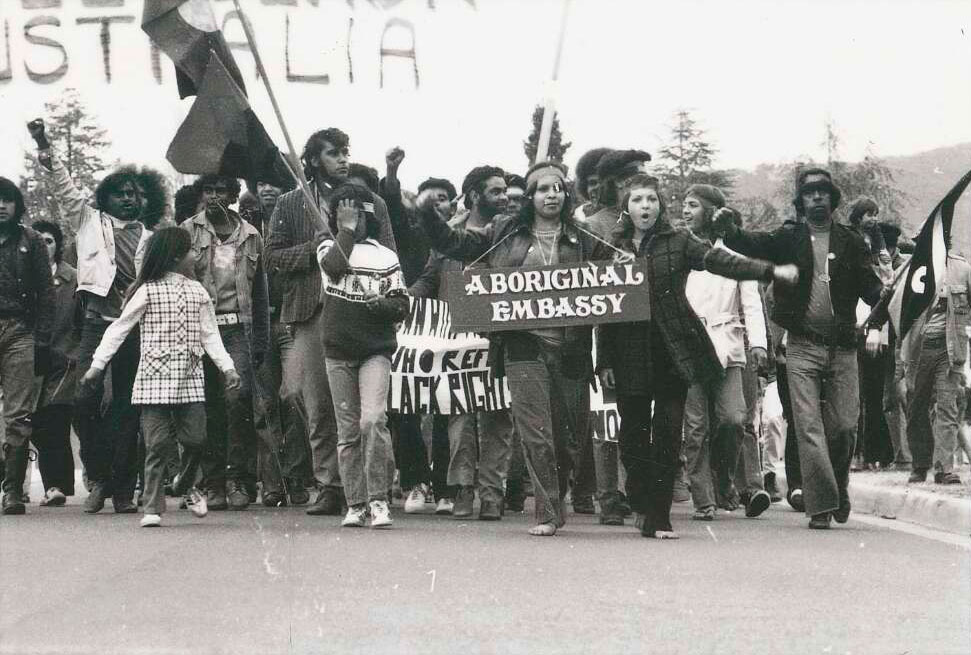

In 1966 the Wave Hill Walk-Off by Gurindji stockmen inspired many Anangu to return to their country. They lobbied the Northern Territory Government for the rights to their lands, and expressed concern about the effects of mining, grazing and tourism, and the damage of sacred sites.

But the area was left out of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, which meant the Anangu could not claim rights to the land.

This changed in 1983 when the Hawke government was elected. In November the government announced that the Aboriginal Land Rights Act would be changed and the title for the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park given to the Anangu.

Research task

Search the Museum’s collection for objects, photographs and paintings related to Uluru. Look closely at one. What does it tell you about Uluru?

‘My family were here for Handback. They really felt strongly about not leaving their country. It’s grandfather’s and the ancestors’ land.’

When was Uluru handed back to the Anangu?

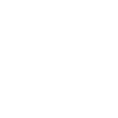

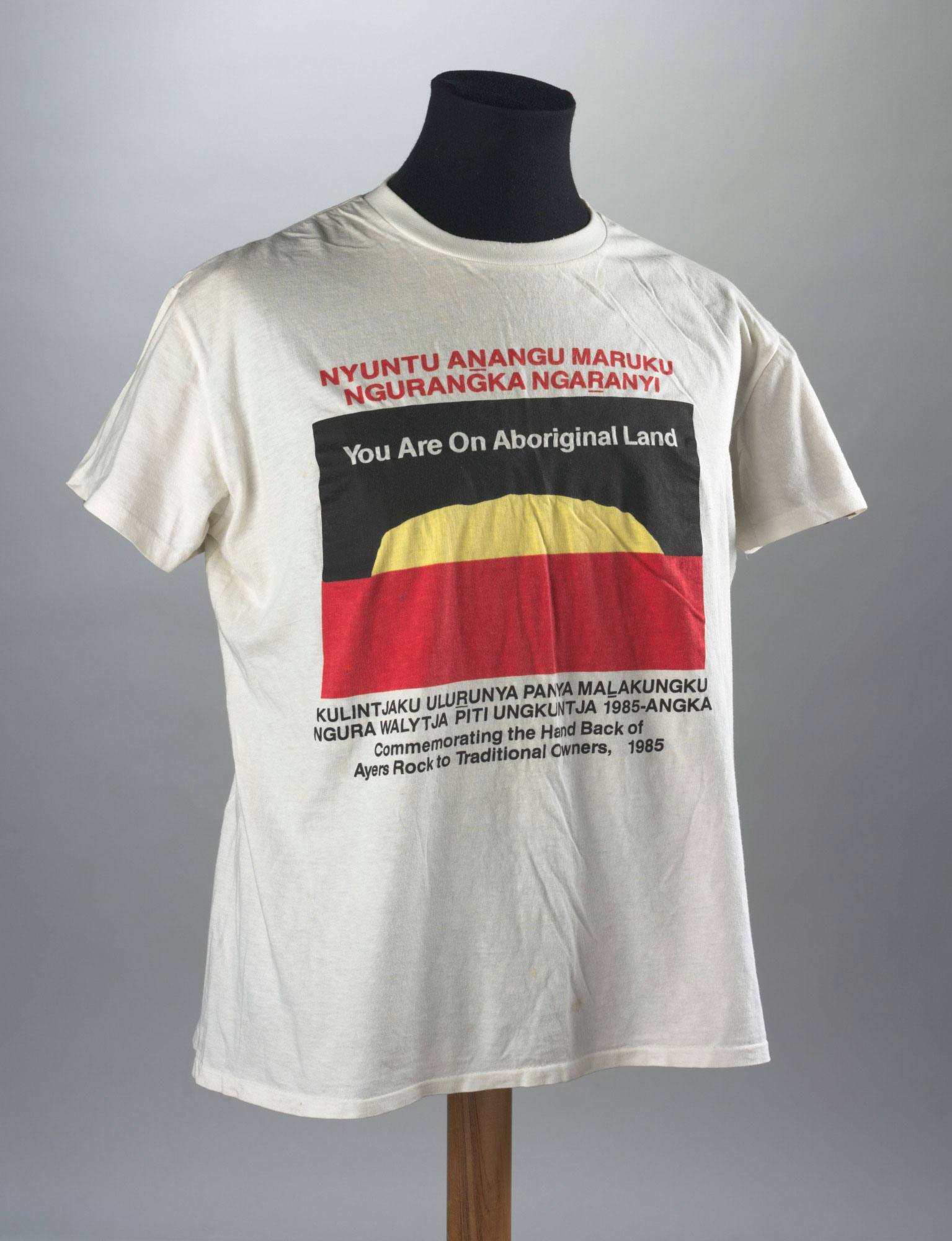

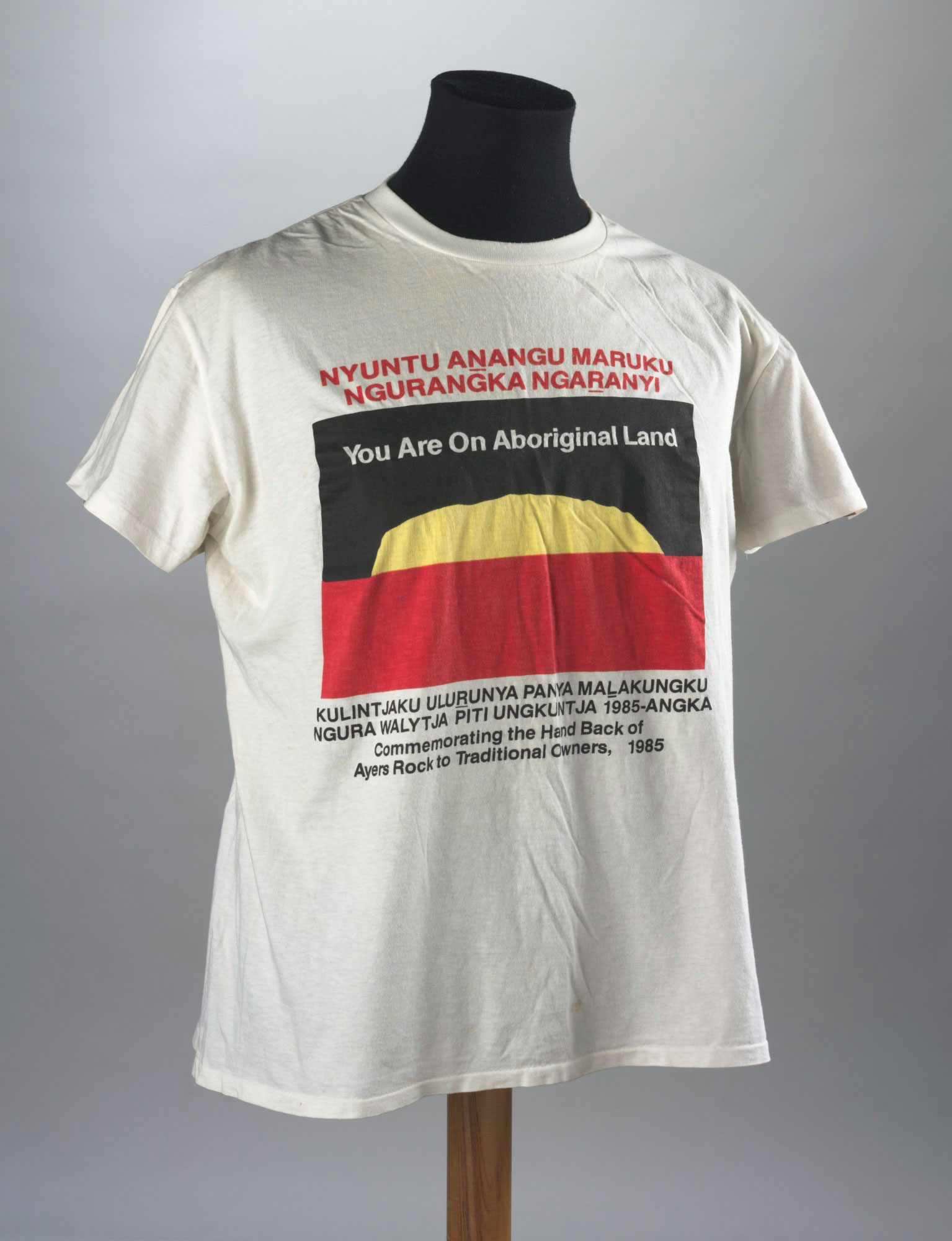

The ceremony to hand back the title took place at the base of Uluru on 26 October 1985. More than 2,000 Indigenous and non-Indigenous people looked on as Governor-General Sir Ninian Stephen presented the title deeds to Uluru-Kata Tjuta. The traditional owners then signed an agreement to lease the park back to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service for 99 years.

Research task

Can you identify at least one other place in Australia that has been returned to its traditional owners?

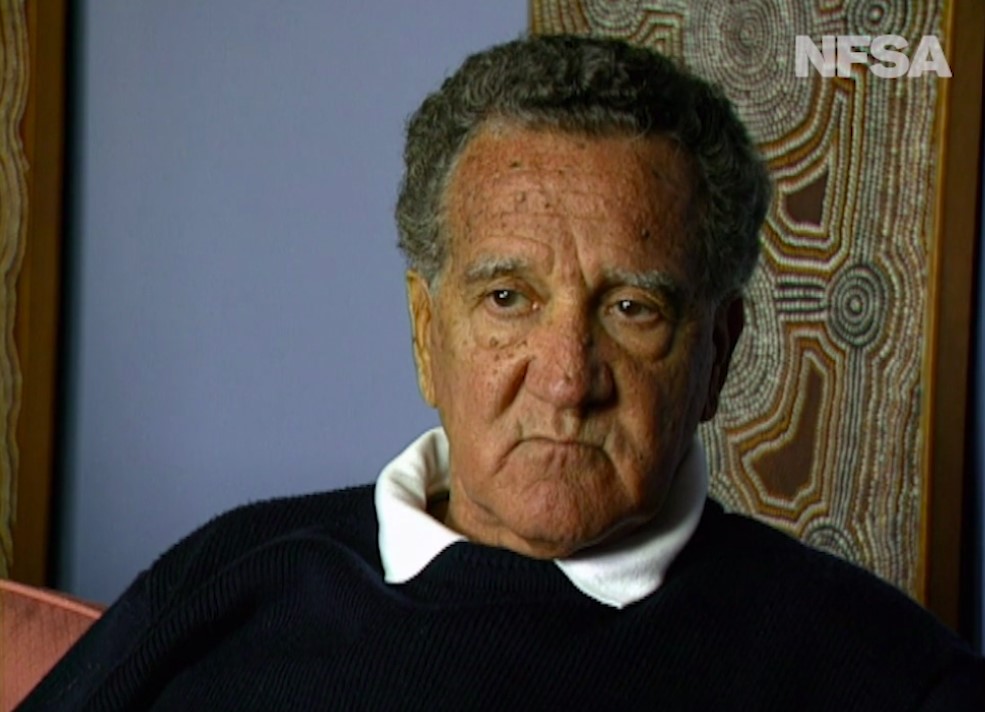

‘The land was being returned to its original owners, so we were happy. Long ago Anangu were afraid because they were pushed out of their lands. And because of that Anangu left. But now a lot of people want to come back. That’s good. It’s our place, our land.’

Traditional owner Reggie Uluru, 2015

A management board was set up to make decisions about the park. The board members are mostly Anangu, along with government representatives. The park is still jointly managed today.

In 1987 the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List for its natural values. In 1994 the park was also added to the list for its value as a living cultural landscape.

A cultural centre was opened in 1995. In 2000 the Sydney Olympic torch started its journey by circling the base of Uluru.

Why has climbing Uluru been a problem?

Although William Gosse was probably the first European to climb Uluru, the first recorded climb was in 1936. The number of people climbing the rock soon increased and some died during the climb. In 1966 a chain was added to part of the climb, for climbers to hold on to.

Traditional owners were not consulted as further changes were made, such as extending the chain in 1976. The climb attracted more and more tourists. Over the years 37 people died climbing Uluru and many more needed to be rescued. The Anangu feel deeply responsible for visitors’ injuries and deaths.

There were many other problems caused by climbing Uluru. Climbers caused erosion and left waste that washed into nearby waterways. A species of shrimp that lived in pools on the rock was almost driven to extinction.

Most importantly, Uluru is a sacred site for the Anangu. The Anangu have always believed that climbing Uluru is against the Tjukurpa, the belief system that guides every aspect of their lives. The tourist trail up Uluru followed the traditional path taken by ancestral Mala men when they arrived at Uluru.

In 2010 the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Plan of Management agreed that the board would look at closing the climb forever when less than 20 per cent of visitors made the climb and other conditions were met. By 2015 the number of people climbing fell to 16.5 per cent. In 2017 everyone on the board voted to ban the climb from October 2019.

The Uluru climb was closed after a ceremony at Uluru on 26 October 2019, exactly 34 years after the government gave back the lands to the Anangu.

Read a longer version of this Defining Moment on the National Museum of Australia’s website.

What did you learn?

What did you learn?

1. Who are the traditional owners of Uluru?

2. Who was the first known European to visit Uluru? What did he name it?

3. What have been some of the problems associated with climbing Uluru?