Learning module:

War correspondents

War correspondents

11. Trial by fire: Gallipoli

You head down to the telegraph office. You have the details for Blake Ross, Mr Callister’s London contact. You send him a message:

‘What is happening in the war? What is the attack on Gallipoli about?’

This is what you find out...

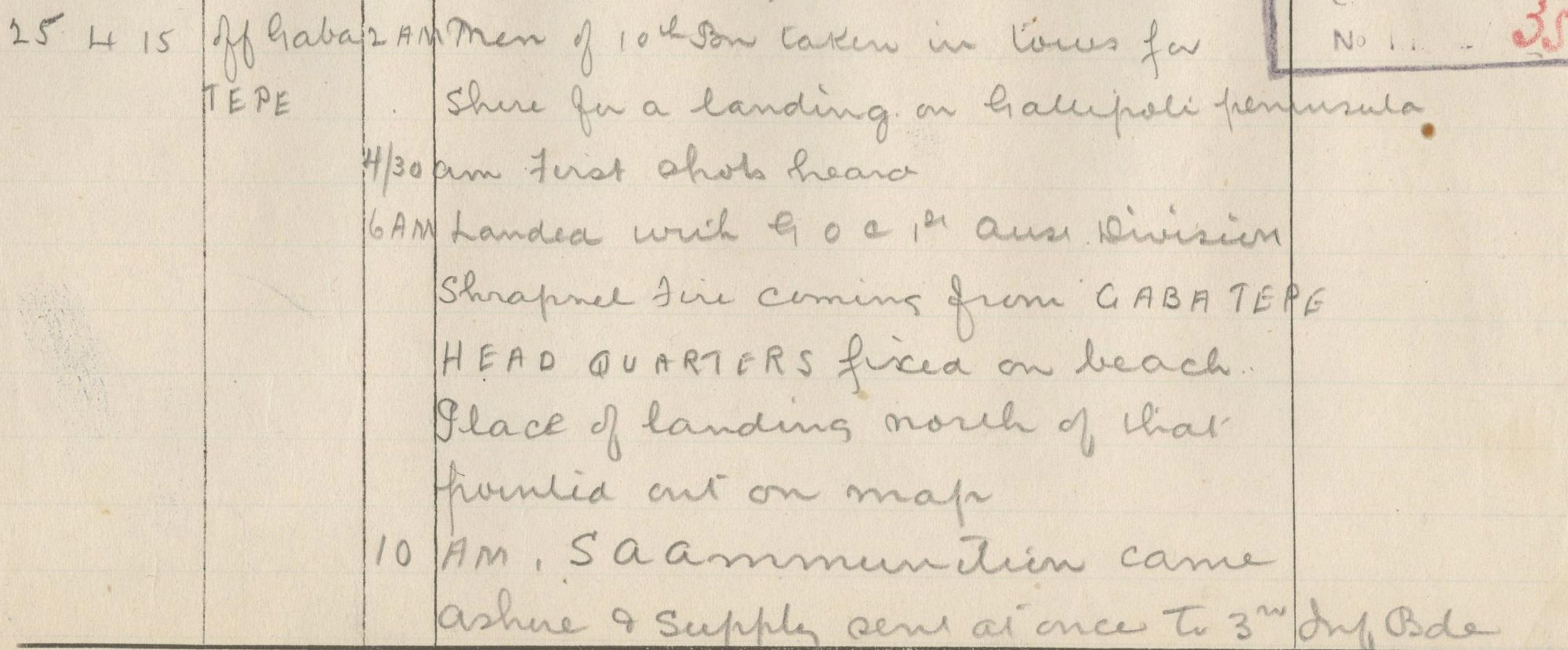

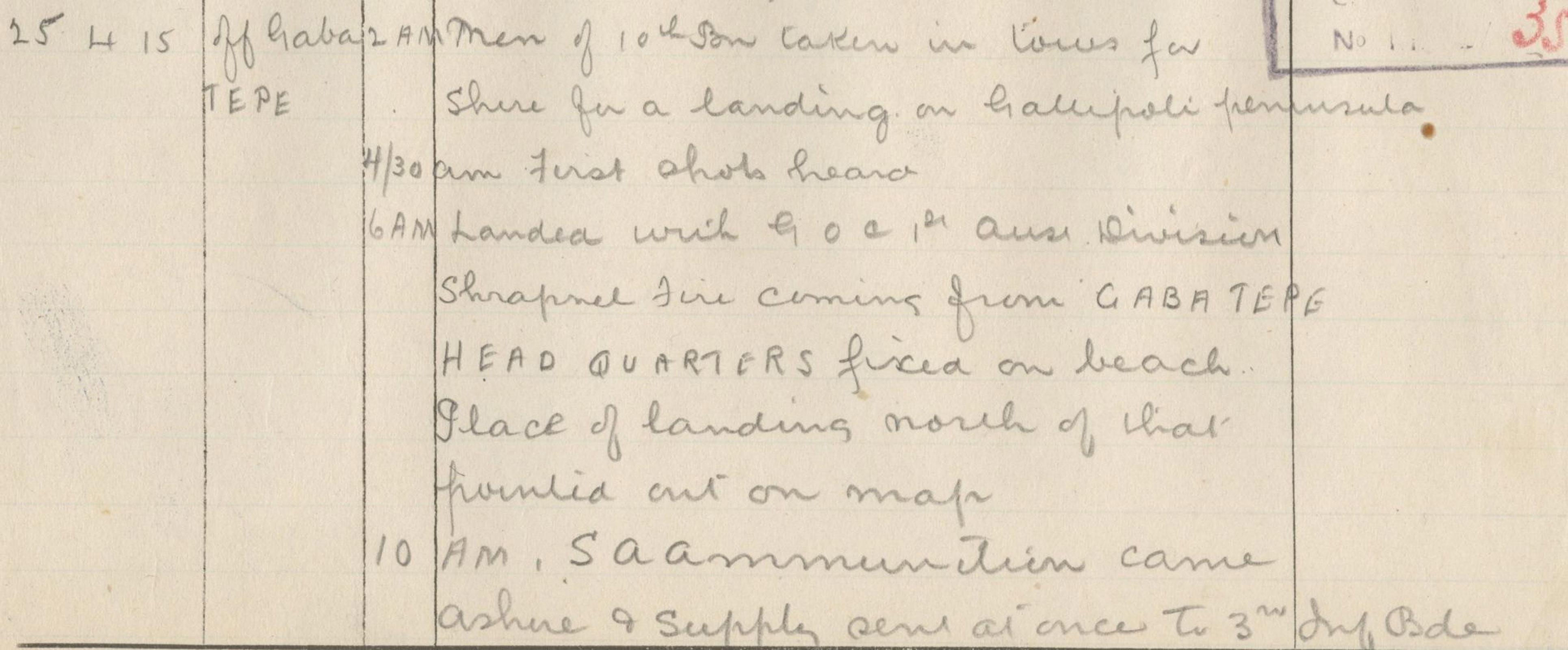

On 25 April 1915 Australian soldiers landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula, in Turkey after a British and French naval attack on the Dardanelles had failed.

For the vast majority of the 16,000 Australians and New Zealanders who landed on that first day, this was their first experience of combat. By that evening 2000 of them had been killed or wounded.

The landing

On 25 April 1915 (now Anzac Day) 16,000 Australian and New Zealand troops landed at what became known as Anzac Cove as part of a campaign to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula.

The British had been trying to force their way through the narrow straits, known as the Dardanelles, to capture Constantinople, and so relieve pressure on their Russian allies who were engaged with Ottoman forces in the Caucasus. Minefields and onshore artillery batteries thwarted the early naval attempts to seize the strait, and it was decided that troops would have to be landed on the peninsula to overcome Turkish defences.

British and French forces landed at Cape Helles on the southern tip of the peninsula. Meanwhile the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), which included the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Australian Brigades along with the 1st New Zealand Brigade, as well as artillery units from the British Indian Army, landed on the west coast in a series of waves.

In the early morning darkness, Australian troops landed over a kilometre or so north of their planned objective, in an area of steep, rugged terrain. New Zealand troops followed later that morning.

Once on the beach, many units became separated from one another as they began moving up the tangle of complex spurs and ravines. The Turkish defenders fell back at first, but resistance stiffened as reinforcements arrived. As the day progressed, the Anzacs were subjected to devastating artillery bombardments.

The Turkish forces were led by Mustapha Kemal (later known as Kemal Atatürk, President of Turkey). Kemal’s orders to his men are said to have been: ‘I don’t order you to fight, I order you to die. In the time it takes us to die, other troops and commanders can come and take our places’.

The ANZAC position became progressively more precarious as the Anzacs failed to secure their high-ground objectives. The Turks mounted a fierce counterattack, regaining much of the ground the Anzacs had taken.

That evening, Major General William Bridges, commander of the 1st Australian Division, and Lieutenant-General Sir William Birdwood, commander of ANZAC, both advised General Sir Ian Hamilton, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, that the Allied force should be withdrawn from the peninsula.

After consultation with the Royal Navy, Hamilton decided against an evacuation and ordered the troops to dig in. Falling back on improvised and shallow entrenchments, the Anzacs held on for a crucial first night.

By that first evening 16,000 men had been landed but more than 2000 had been killed or wounded.

Stalemate

For the next eight months the Australians advanced no further than the positions they had taken on the first day. The British and French forces who were farther south were also unable to break out of their positions despite a massive new offensive in August costing thousands of casualties and fought through the terrible heat of summer. Sickness was widespread and conditions appalling.

By November, with more Turkish reinforcements and German equipment in place, it was obvious the stalemate would continue. The onset of winter flooded the trenches. Men froze to death after heavy snowfalls and the fleet found it more and more difficult to land supplies and reinforcements. Lord Kitchener, the British chief of staff, visited the peninsula and recommended to the British Cabinet that a general evacuation take place.

In late December the Anzacs were successfully evacuated with barely any casualties, and by 20 January 1916 all Allied troops had withdrawn from the peninsula.

The Anzacs that survived the Gallipoli campaign were sent to Egypt. There they were joined by other volunteers from Australia. These soldiers were sent to the Western Front in 1916. Some soldiers stayed in Egypt and fought against the Turks in desert battles.

The Gallipoli campaign was a military failure. However the traits that were shown there — bravery, ingenuity, endurance and mateship — have become enshrined as defining aspects of the Australian character.

Your task

The story is hard to listen to. So much bloodshed! But many believe the shedding of blood is the making of men and nations. The Age wants you to not only tell the story but give an analysis of some of the photos coming out of the war. You get in touch with the senior journalist Emma Pratt again and she explains to you what it means to ‘identify patterns or themes in a source’.

‘Identifying themes in a source means looking beyond just what you see in the source, to the overall meanings you can find in the source. If you have ever studied a book, you may have been asked to find themes in it. Themes are things like conflict, sorrow, happiness, justice and friendship’, says Emma.

‘Finding patterns in a source doesn’t mean finding patterns like diagonal lines or polka dots! It means seeing connections between different elements in a source and thinking about what these might mean’, she says, handing you a photo.

‘Look at this photo. I can see patterns in it — the men on the beach are often looking out at the boats and the men on the boats are looking at the men on the shore. What might this mean? Perhaps it shows the importance of the moment — the men on the shore are looking out at sea because the new supplies are really important for the campaign. For those on the boats, it might show that they are focussed on getting ashore as quickly as possible’, she says.

She takes back the photo, looks at it for a moment, and then says, ‘As for themes, in this photo I see confinement. There is a lot of gear and lots of soldiers packed into a small space. Things are piled high as there isn’t much room to move.

‘So if you wrote down those two things, you would be identifying patterns and themes in a source.’ She hands you another photo, ‘Your turn.’

Write your source analysis, identifying patterns or themes in the source. You should write at least seven sentences.

You submit your report to head office.

The next day you receive a message from Emma. She wants you to come to her office. She has been doing some research about the causes of the war and Mr Callister wants you to write a report about it. Go to 12.