Learning module:

War correspondents

War correspondents

32. Women and the war

You make your way to the Red Cross office, a clean but run-down looking building in the city centre. Lots of people are coming and going, carrying boxes of supplies from a dark warehouse in the next building over. Your contact is Alana Warner, a senior officer.

‘Women didn’t fight on the front line. War isn’t considered a very feminine thing to do. We weren’t even given the option of signing up for that’, she says at the outset.

You go to a café around the corner for a cup of tea, writing in your notebook as she talks passionately.

‘Of course many of us began our service in the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). We dealt with a lot of suffering and all kinds of injuries. I went over with the first draft of nurses in September 1914, right at the start of the war. We nurses followed the Australian troops wherever they were sent.’

She fumbles around in her pocket for a piece of paper.

‘Here it is, I managed to get some numbers for your story. There were 2139 nurses who served overseas. Another 423 of us served back here in Australia. 25 of my nursing sisters died in the war. I received a medal for my service. So did another 387 women. And nurses worked outside of the AANS as well. Many served with the Red Cross or joined up with British units.’

She sips her tea.

‘The Red Cross and the Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau were very active back here in Australia. I joined the Red Cross after I came back from my nursing service. We organised interviews with the survivors of the most terrible battles, hoping to learn the fate of the ‘Missing’ in order to offer some kind of closure to their families. We also helped soldier morale by packaging up and sending supplies — things like clothing, tobacco and medicine. They longed for the taste and smell of Australia. You might have seen some soldiers opening some of our care packages when you were over there?’ she asks.

‘Yes, they really appreciated that touch of home!’ you recall.

‘The real contribution of women has been when weary and shell-shocked soldiers come back from the war. We are the ones having to hold together these broken families — dead fathers, dead brothers, men coming home depressed, missing a leg ... shell shock is a big one too.’

You ask about the other kinds of contributions women made.

‘A lot of fundraising. War is an expensive business! Millions of hours of unpaid labour underpinned the war effort, with women organising themselves along military lines to do that work efficiently and effectively. We took on responsibilities we had not really had before. War work gave us a sense of purpose and connected us somehow with loved ones serving overseas.’

‘What about paid work’, you ask, remembering what you saw in England.

‘Australia wasn't like the old country’, she replies. ‘In Britain women took men’s places in industry, freeing up men for the war effort. They did all kinds of work — driving buses, working in factories and of course making munitions. In Australia far fewer women worked outside the home during the war, and those that did mostly worked in the clothing, printing and food industries. Some women took on office roles which had been seen as largely men’s work before the war. Of course women were paid much less than the men had been and there was pressure to resign and give the jobs back to the men once the war was over.’

‘That’s hardly fair!’, you say.

You’ve got enough for your story, so you thank Alana for her time, walk back with her to the Red Cross, make a small donation and head back to the Age to write up your article.

Your task

Mr Callister wants to do a special on the recruiting posters of the war. He is going to put a poster in the newspaper and he wants you to write some text to go with it, to help people understand it.

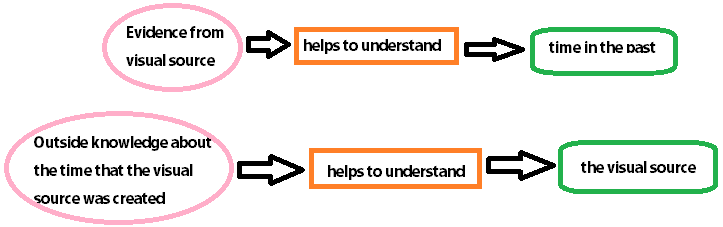

A visual source can tell us a lot about a time in history. However we can also use our own knowledge about a period in time to help understand a visual source. There are two different skills that you could use here. Consider this diagram:

What we are talking about here is the second one — using outside knowledge to help understand the source.

You have learnt a lot about the First World War and are now beginning to be able to use that knowledge to understand sources.

Look at the poster below and answer the questions that follow.

1. What does ‘remember how women and children of France and Belgium were treated’ mean? How do you think they were treated?

2. What kind of treatment is the poster suggesting women would get?

3. Who are the figures on the ground?

4. Where do you think the village in the background is?

5. What is this poster trying to make women do?

You file your story. As Monday morning rolls around, you are walking to the Age office when a man grabs you by the arm. ‘You’re that ace war reporter for the Age, aren’t you?’ You are reluctant to say yes to a person who has grabbed you on the street.

‘I’ve got a news story for you. It’s about a massive government failure. The government doesn’t want to talk about it but I can give you a scoop if you want?’

‘What is it about?’ you ask.

‘The government spent all this money trying to set up soldiers on the land when they came back from the war. Total failure if you ask me. Buy me lunch and I’ll tell you all about it.

’He seems a bit batty, but sincere. This definitely sounds like a story your boss would like to run, so you agree to buy him lunch, and follow him to a nearby restaurant. Go to 20.