Australian Journey Episode 02: A Land of the Weird and the Monstrous interview

The dangers of narrowing biodiversity with Susan Carland, Kathryn Medlock and George Main.

View transcript

+ -SUSAN CARLAND: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this series may contain images, voices or names of deceased persons.

BRUCE SCATES: Welcome to ‘Susan Carland: In Conversation’. This interview is a supplement to Episode 2 in the Australian Journey series, ‘A Land of the Weird and the Monstrous’.

SUSAN CARLAND: I’m in the old vault of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. And I’m surrounded by all these boxes of some of the last remaining physical evidence of that remarkable creature, the thylacine. Joining us to talk about this today is curator Kathyrn Medlock. Kathryn, thanks for joining us.

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: That’s fine.

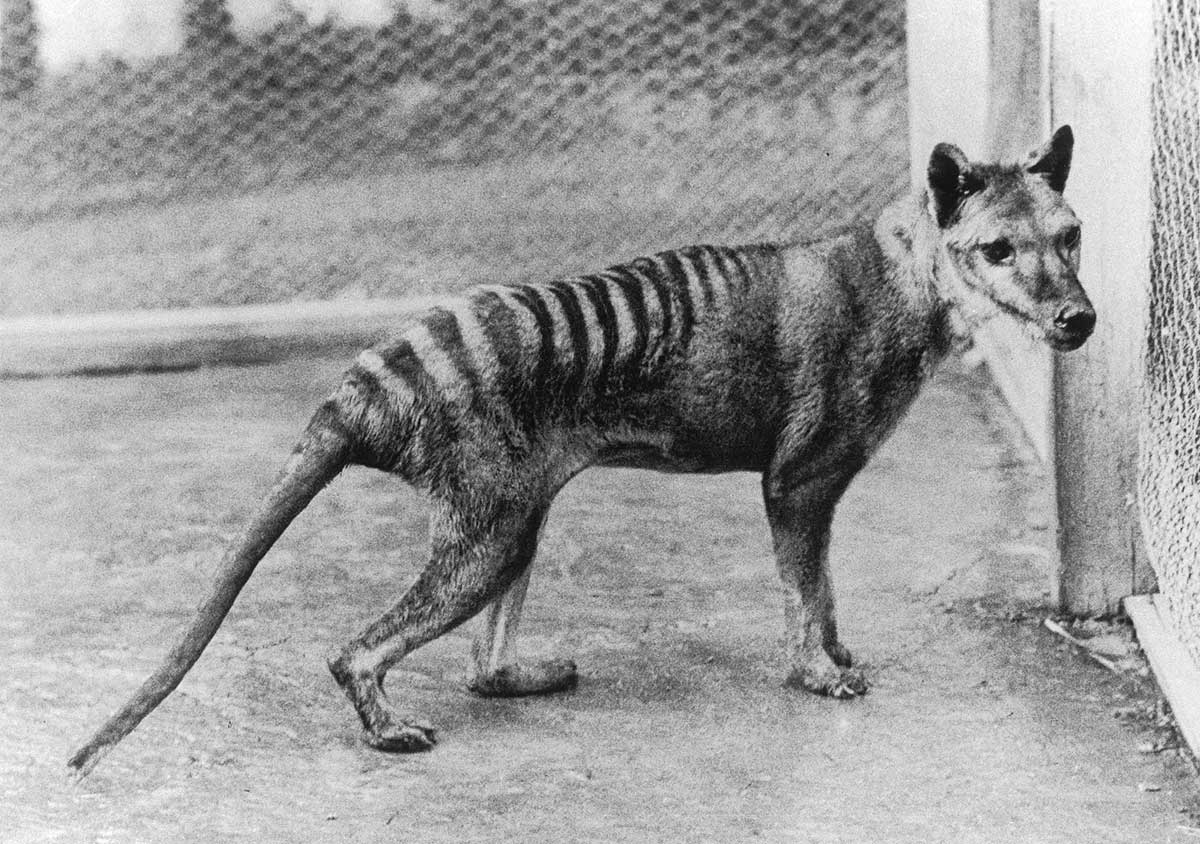

SUSAN CARLAND: Kathryn, we mostly know the thylacine by its more popular name, the Tasmanian tiger – but did the thylacine ever exist anywhere else? Perhaps on the mainland of Australia?

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: Yes, it did exist all across Australia but by the time Europeans arrived in Tasmania in 1803 it was confined to the island which was cut off by Bass Strait. The theory is that it went extinct on the mainland with the introduction of the dingo from northern Australia around 5,000 years ago.

And so, when Europeans arrived, they’d heard that there was this large carnivore in the bush. They were a bit fearful of it. They gave it the name ‘Tasmanian tiger’, ‘Tasmanian wolf’, ‘Marsupial hyena’. So, all these names were connoted a fear, and a worry about having such a horrible, fierce animal.

SUSAN CARLAND: I understand that in Tasmania the destruction of the thylacine was really part of a deliberate government policy. Is that correct?

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: Yes, the Tasmanian Government introduced a bounty on the thylacine in 1888 and that was because the agricultural industry was getting established and they wanted to have sheep farming and they blame – it was difficult, they had a difficult time getting sheep farming going, and they blamed the thylacine for sheep losses.

But it’s most likely it was wild dogs roaming around. There are only a couple of reports of thylacines killing sheep and no doubt thylacines would have got sheep but it probably would have been sickly young lambs and, and things like that. But it was a convenient scapegoat.

So the farmers lobbied the government and eventually to save sheep farming the government placed a bounty on the thylacine, and they paid one pound per head for a dead animal and five shillings for a young animal. And over 2,000 animals were killed under this scheme, so it was very destructive for the population. Although, saying that, there were some people that were against the bounty. It only went through Parliament by one vote. Yes, some people did – were concerned that the thylacine might go extinct and that goes right back to the 1860s. John Gould, the famous ornithologist, he predicted that the mammal might go extinct but having a bounty on the thylacine – it was also – it was a convenient way to give farm workers a bit of extra income.

The bodies had to be destroyed so the museum wasn’t very happy about that because it prevented museums from getting specimens.

SUSAN CARLAND: Why did the bodies have to be destroyed?

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: To prevent them making a second claim.

SUSAN CARLAND: Ohhh! Some environmental historians explain the policy to destroy the thylacine using the term ‘placental chauvinism’. Can you tell me what that means?

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: Yes, well the first thing to understand is that the Tasmanian tiger was a marsupial. Its young are born at a very, very early stage – probably no bigger than that – and they crawl into their mother’s pouch, and then they finish their development in their pouch just the same as a kangaroo, a koala, those more familiar marsupials. And there was this idea that marsupials were somehow inferior to placental mammals, like dogs and cats that give birth to their young at an advanced stage.

So there were many reports of marsupials being dumb, you know. In zoos, they reported them – they said they were boring and not very interesting. I mean they were interesting to zoologists, but generally the idea was that they were inferior to placentals so that no doubt coloured people’s ideas about the value of this animal. And they didn’t really see it as being an important part of the Tasmanian environment.

SUSAN CARLAND: What you said about the marsupial – these were not, in fact, taken ‘in utero’. These were taken from the mother’s pouch.

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: Yes, each one of these baby thylacines was taken from their mother’s pouch. They were born when they were very, very small and they probably lived in the pouch for five or so months. We’re not really sure. The mother could have up to four young in her pouch at one time and they would have to stay in their mother’s pouch at least until they got fur, so they could be out and about. And even then, they probably would go in and out of the pouch a little bit, just like kangaroos do. Very, very much the same.

Unfortunately, we don’t know how long they stayed in their mother’s pouch for, because nobody did ecological or behavioural studies in those days.

SUSAN CARLAND: Wow

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: This one here is probably around about four months old, we think. It was collected in 1902 and the mother had two young in her pouch at one time. And you can see they haven’t got their fur on them yet. They’re at a quite early stage of development – they wouldn’t have been able to survive out of their mother’s pouch. They wouldn’t leave the mother’s pouch until they had fur and they were able to sort of be, more or less, kept warm, and a bit on their own.

SUSAN CARLAND: That’s remarkable.

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: Yes, they’re very interesting specimens. The mother of this animal here was killed in the bounty scheme – it came from central Tasmania. And the two young were taken out of the mother’s pouch and the mother animal was sent to the – to Sydney University for dissection.

SUSAN CARLAND: So, do you think there’s any chance that the thylacine could still be out in the wild?

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: Well, unfortunately there has been no verifiable evidence of a thylacine in the wild since the last one died in the Hobart Zoo in 1936. There has been no body, there’s been no roadkill. No one’s found any evidence of them, which is very sad actually, but it’s difficult to prove something’s not there. You can always prove it’s there, but you can’t prove its absence.

There’s – no doubt the thylacine did survive after 1936. There would have been some out in the bush – and there are stories that there have been people who had sightings. But unfortunately sightings don’t cut it – you need evidence.

SUSAN CARLAND: Today the thylacine is celebrated all across Tasmania. You can see pictures of the Tasmanian tiger everywhere, even on my taxi, it was on the number plate. But that wasn’t the attitude in the early 20th century, was it?

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: No, it certainly wasn’t, and I find that really interesting actually. In the early 20th century and in the 1800s, it was certainly seen as a pest. People didn’t want to be reminded of it. They just wanted it destroyed and gone.

I have a story from a woman. She told me that her uncle had a thylacine skin, and it was hanging up in the wall in his house. ‘When he died,’ she said, ‘my mother and I, that was the first thing we put on the fire. We didn’t want to be reminded of this animal’.

And then it sort of changed. About the 1970s it seemed to change, and people started sort of getting a bit more of an understanding of what was gone. I guess with more emphasis on ecology and environment and things like that.

And it’s become an icon. It’s really an international icon of extinction now and it’s an international – and it’s a very much a symbol of Tasmania, as well. It’s on our state coat of arms, number plates, it’s everywhere.

SUSAN CARLAND: Museums like this one have a lot of great specimens of the thylacine and some may even still contain DNA. Some scientists think that, like in Jurassic Park, we could extract that DNA to recreate the thylacine. Do you think that’s possible or even desirable?

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: Well, it’s not possible at the moment but who’s to say it won’t be possible in the future?

These specimens were collected a hundred years ago, and these are the sort of specimens that are the focus of a lot of those programs. They’re stored in ethanol which doesn’t destroy the DNA too much but there – no doubt the DNA will be degraded. But you can’t say it will never happen. That molecular science is going ahead really quickly so it could well happen one of these days.

As to whether it’s desirable or not, that’s another issue. You know … and it’s ethics, it’s ethical too. I sometimes think that if they got a thylacine, a live thylacine, it’s going to be a really valuable animal. Is it going to be any better off than the poor last one that was in the zoo, in the film footage?

Are they going to put it back into the Tasmanian bush? You need a population. The first one that they get, it won’t have a thylacine mother. So, we don’t know how much they were maybe taught by their mother or father or siblings.

All those questions, we don’t know. And also, I wonder if it was reintroduced, what would the farmers think? Would they again start persecuting it and not liking it? Who knows?

And the other thing is that the Tasmanian environment, sort of, it hasn’t recovered completely from the loss of the thylacine but its changed. So, you’ll be putting an animal back into an altered ecology. We don’t know what effect that will have. So, there’s a lot of questions, a lot of questions.

SUSAN CARLAND: And remember from Jurassic Park, the new animals always turn on their makers, so...

KATHRYN MEDLOCK: Yes. You never know, you never know.

SUSAN CARLAND: Kathryn, thank you so much to you and all your colleagues here at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

And you can learn more about this museum’s fantastic collections online. The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery is in Hobart, and you can get here straight from a flight from Melbourne, or across the Bass Strait on a ferry, and it’s well worth a visit.

Tasmania isn’t the only place you’ll find physical evidence of the thylacine. Here in the National Museum of Australia they have a number of important specimens of the thylacine and joining me to talk about this today is Dr George Main, Senior Curator here at the National Museum of Australia. Thank you for joining me.

GEORGE MAIN: Oh, you’re welcome.

SUSAN CARLAND: George, I understand that the mainland did once contain thylacines. Can you tell me more about how they existed here and what collections do you have here at the museum that can explain that situation?

GEORGE MAIN: We know that thylacines lived on the mainland. There’s a lot of specimens that have been found around the country, including this extraordinary, mummified thylacine head which is thousands of years old.

Well, we have it on loan from the Western Australian Museum. It was found in a cave on the Nullarbor Plain in Western Australia. So, it’s an extraordinary item and it’s one of a number of specimens and bones that have been found across the country.

And we also know the thylacine lived on the mainland because Aboriginal rock art across the country represents thylacines.

SUSAN CARLAND: I know that in Tasmania the thylacine was hunted to extinction. Is that what happened on the mainland as well? Or was there some other situation?

GEORGE MAIN: Oh look, there’s conflicting theories. One idea is that the introduction of the dingo about 4,000 years ago from the north of Australia led to the destruction of the mainland thylacine. Dingoes are bigger than thylacines – they hunt in packs, they’ve got bigger brains and it’s thought that they may have actually, you know, hunted thylacines to extinction, or also competed for food, for prey species.

And another theory is that around the same time, human populations were increasing substantially in Australia. People were becoming more sophisticated in their hunting and gathering techniques, and they could have also, you know, like in Tasmania, have been hunting the thylacine, and also perhaps competing for food.

SUSAN CARLAND: And was the climate very different on the mainland to Tasmania?

GEORGE MAIN: Ah, about at the same time as the dingo arrived in Australia, we did go through a period of climate variability, which didn’t affect Tasmania in the same way, and it is thought that, that variability may have made conditions more difficult for thylacines and may have been a factor in their demise.

SUSAN CARLAND: This is an amazing piece. Do you have anything else here at the NMA that you would consider to be a really important specimen of the thylacine?

GEORGE MAIN: We do. We actually have here, in our back of house storage areas, the only adult, full adult specimen of a thylacine known in the world.

SUSAN CARLAND: Oh wow! Well, let’s go check it out.

GEORGE MAIN: Terrific.

SUSAN CARLAND: And here we are. So where is this specimen from?

GEORGE MAIN: Well, it came to the Museum from the Australian Institute of Anatomy Collection which was put together by Sir Colin McKenzie who was an orthopaedic surgeon who also had a role in developing the Healesville Sanctuary in Victoria, near Melbourne, and it’s thought that he may have acquired this specimen from that sanctuary.

SUSAN CARLAND: Right! Now George, I know some scientists think that it might be possible to clone a living thylacine, that there might be enough intact DNA in specimens that they can extract it and bring it back from extinction. Do you think this is possible and do you even think that this would be a good idea?

GEORGE MAIN: Well, some scientists think it could be possible. I do know that a number think it wouldn’t be possible – that this sort of mode of preservation doesn’t allow for enough DNA to be abstracted. But I mean, if it is possible, it’s going to be a very expensive and time-consuming process and some people do argue that the resources that would go – have to go – into that process could be better spent on protecting the habitat of species that are now endangered and that are at risk of going extinct.

And I think there are some other issues too about efforts to clone an extinct species. I mean it does tend to give people an understanding that maybe science can step in and save the day, whereas really what is happening in a lot of these extinction events, and, and we’re living in the midst of a massive extinction event at the moment, is that people are acting, you know, societies are acting in destructive ways for cultural reasons that are really complex, and if we rely too much on science and technology to get us out of these sorts of problems and to, you know, bring species back from the dead, it seems to me that that gets in the road of addressing some of these big cultural questions that are really at the heart of the extinction process.

SUSAN CARLAND: Right. Yes, I see. George, thank you so much to you and your colleagues here at the National Museum of Australia.

GEORGE MAIN: That’s a pleasure.

SUSAN CARLAND: And you can learn more about the way the Museum grapples with these big cultural questions at their online collections. And remember, no visit to Australia’s national capital is complete without a tour of our National Museum.

Activities

1. According to the curator at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, why did many Europeans want to eradicate the thylacine?

2. What kind of animals were thylacines and why did this influence European attitudes?

3. According to the curator at the National Museum of Australia what are the theories for why the thylacine became extinct on the mainland of Australia?

Details

+ --

Themes:

-

Types: