Australian Journey Episode 09: Encounters

Warning: this page contains some potentially distressing language and content. Viewer discretion is advised.

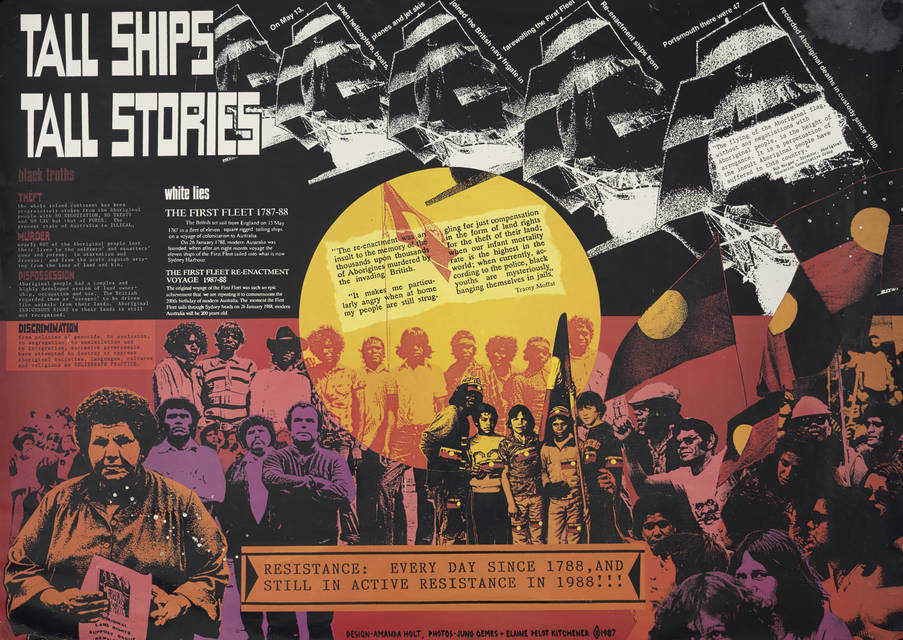

Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander resistance, survival and reconciliation from the ‘Encounters’ exhibition.

Note: This webpage was first published in 2020. More recently some scholars have questioned the provenance of the shield in the exhibition.

View transcript

+ -SUSAN CARLAND: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this series may contain images, voices or names of deceased persons.

BRUCE SCATES: This episode – ‘Encounters’ – is part of the series that examines the concept of nation.

We’ll begin with a remarkable museum exhibition; we’ll cross the continent from east to west exploring the ways that Aboriginal people resisted the invasion of their homelands; and we’ll end in the port city of Fremantle with a story of survival and reconciliation.

SUSAN CARLAND: We begin today’s episode here at the National Museum of Australia, and one of the most successful exhibitions the Museum has ever hosted so, let’s check it out.

BRUCE SCATES: The ‘Encounters’ exhibition is a remarkable cultural collaboration. It involves a partnership – a partnership between our National Museum and the British Museum over in London.

Around 150 objects, all of deep and lasting cultural significance, have been air freighted here from Britain. These items date from the 1770s and they represent the first point of contact between Europeans and Indigenous Australians. And you know, this is the very first time that most of them have been returned here to the country and the communities that they came from.

SUSAN CARLAND: Those 150 precious items are remarkable enough. They are physical evidence of the world’s oldest surviving civilisation. But equally important is the way they’re presented in this exhibition. Each object has been placed in a kind of module, representing its place of origin. And around these ancient artefacts are contemporary objects fashioned by today’s Indigenous communities.

We’re walking down a long tunnel, woven together in the form of a fish trap.

BRUCES SCATES: It’s a passage into this beautiful and evocative space, but it’s also a powerful sculptural statement – a reminder of the relationship Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have had with this land since time immemorial.

SUSAN CARLAND: This fish trap is also a metaphor for the intertwining of Indigenous and non-Indigenous stories. And at the end of this 30-metre tunnel lies arguably the most eloquent object in this whole exhibition – the Gweagal shield.

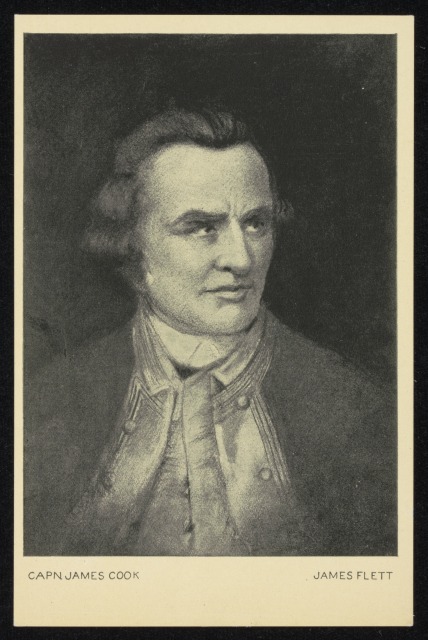

BRUCE SCATES: The shield was taken from Botany Bay on James Cook’s great voyage of discovery in 1770. It literally embodies that first encounter between the traditional owners of this land, the Gweagal people, and the European invader.

SUSAN CARLAND: This shield symbolises dispossession and conflict – it connects us in an almost palpable way to a process of colonisation that still causes pain and anguish today.

BRUCE SCATES: And I’m afraid it’s a story that reminds us of far too many others.

SUSAN CARLAND: No one knows for certain where on Botany Bay the Gweagal shield was taken. Cook’s ship, the ‘Endeavour’, anchored near here in April of 1770.

BRUCE SCATES: What we do know though is that a party of armed marines landed somewhere near here along with an entourage of botanists and scientists and led of course by Lieutenant Cook himself. They’re immediately confronted by two Gweagal warriors and they are brandishing spears.

SUSAN CARLAND: We don’t know what was said. Cook had no knowledge of Aboriginal language or of the elaborate protocol that governed any first meeting with strangers. We do know this encounter ended in violence.

Having failed to communicate, the British fired on the men instead. One Aboriginal man was shot and injured and both retreated into the bush.

BRUCE SCATES: Cook and his party wandered into a Gweagal campsite. Joseph Banks, the famous botanist, could scarcely conceal his delight when he found that shield and a store of about 40 or 50 spears.

Now these were prize scientific curiosities, evidence of what Banks saw as a ‘primitive’, ‘unspoilt’ native culture. So the party carried off virtually everything they could find.

‘We threw into the house to them some beads, ribbons and cloth,’ he wrote, ‘intended as presents.’

SUSAN CARLAND: It seems unlikely that the Gweagal saw that as a fair exchange. And for the next seven days Aboriginal people did all they could to avoid the intruders. Cook’s last journal entry from Botany Bay is telling.

‘All they seem to want’, he wrote in the ship’s journal, ‘was for us to be gone.’

BRUCE SCATES: So Cook returned to England, taking that Gweagal shield with him. And less than 20 years later, more ships arrived to establish a British penal colony here in Australia.

Again, no one sought the Gweagal’s consent to land. Indeed Cook’s last act on leaving the Australian coastline was to declare the whole eastern seaboard of this continent the possession of Great Britain. And really, really that clumsy encounter here seems to have set a pattern right across the country.

SUSAN CARLAND: Cook claimed much of the continent under the doctrine of ‘terra nullius’. Australia was seen as an empty land, a vacant title. Cook told the authorities in London that Aboriginal people were few in number, that they lived only on the coast, and that they were unlikely to oppose European settlement. Most important of all, Aboriginal people made no real use of the land they occupied.

So far as Cook could see, they didn’t farm, they didn’t irrigate, they didn’t – in that discourse of the Enlightenment – ‘improve’ the land the way Europeans would.

BRUCE SCATES: And on each and every point James Cook was wrong. We don’t know how many Aboriginal people occupied Australia prior to the European invasion. Estimates range from a few hundred thousand to well over a million. What we do know is that Aboriginal people had settled in every corner of the continent, and their attachment to the land was affirmed through every story of the Dreaming.

Indigenous Australians may not have tilled the soil, but firestick farming, the practice of regularly burning the bush, had created vast areas of open parkland. So this – this was not an empty wilderness, it was a vast and a cherished estate managed carefully over countless millennia.

SUSAN CARLAND: Aboriginal people belong to this land and they were – and still are – determined to defend it. Wherever white settlement encroached on Aboriginal lands, it met with resistance.

Europeans assumed that the occupation of this continent would be a simple matter – hundreds of separate and distinct Indigenous communities were declared the subjects of the Crown, with no right to autonomy or sovereignty. But within 50 years of Cook’s landfall at Botany Bay, settlers on the frontier acknowledged a state of open warfare with the Indigenous inhabitants of this country.

BRUCE SCATES: The course of that war changed, it changed as white settlement progressed. In those first encounters, Aboriginal people sometimes had the advantage. Cook’s marines fired on those Gweagal men with Brown Bess muskets. Those weapons were slow to load, unreliable, inaccurate.

To the Europeans, that shield and those ‘lances’ seemed a ‘primitive’ technology. But in the hands of a practiced huntsman a spear or a club could be lethally effective.

SUSAN CARLAND: As the 19th century progressed, the frontier war turned decisively in the whites’ favour. Fast-loading guns, fast-moving horses and sheer military might gave the invader a new advantage. Weakened by white disease, Aboriginal people were forced off the land they’d occupied for generations.

It wasn’t all conflict on the frontier, of course. There are stories too of partnership, negotiation, even compromise. And on every frontier the dynamic of violence and dispossession was different.

Let’s turn now to the last frontier in which these wars of dispossession were fought – Western Australia.

BRUCE SCATES: There are very few monuments to Australia’s frontier wars, but this memorial – set in the heart of Fremantle’s Esplanade Park – is one of them.

SUSAN CARLAND: The monument honours three white explorers. Frederick Panter, James Harding and William Goldwyer were members of an expedition sent to settle the far north-west in 1864.

BRUCE SCATES: All three of those men were killed by Aboriginal people, and their deaths are part of a pioneer myth that is set deep within the white Australian psyche.

SUSAN CARLAND: CJ Brockman, one of Western Australia’s wealthiest pastoralists, built the monument. Brockman made his fortune through the occupation of Aboriginal land and the exploitation of Aboriginal labour.

Here Brockman celebrates the whites as ‘intrepid pioneers’. Aboriginal people, by contrast, are condemned as ‘treacherous natives’. The land Brockman would occupy is described as ‘terra incognita’, an unknown, uncivilised space. The wilderness of the north-west was there for the taking. The whites called that land Le Grange; Aboriginal people knew it as Bidgidanga.

BRUCE SCATES: In the 19th century and well into the 20th, white Australia saw the deaths of these explorers as an outrage. Panter, Harding and Goldwyer were said to have been ‘murdered in their sleep’, ‘attacked at night’ and butchered by ‘treacherous natives’. And that act of violence triggered a terrible reprisal.

In 1865, a search party sets out from Fremantle. It sails over 1,000 miles to the north and it embarks on a killing spree of terrible proportions.

SUSAN CARLAND: Maitland Brown led the punitive expedition. A life-sized bust of him crowns this granite pedestal. And this bas-relief on the monument’s eastern side depicts the terrible moment when the explorers’ remains are discovered.

BRUCE SCATES: Those figures in chains are two Aboriginal men who brought Brown to the camp. The Karajarri men Brown took captive had been choked by nooses around their necks, locked in the hold of his boat for days, beaten, abused, interrogated.

SUSAN CARLAND: And above all is the figure of Brown himself, one hand raised in the air, determined to avenge the explorers.

BRUCE SCATES: The killing began with the hostages, men whose names Brown never bothered recording. One died quickly, shot in the back. The other lived just long enough to make a full confession of the murder. At least that’s what Maitland Brown told the authorities back in Fremantle. One thing is beyond dispute. The killing of the hostages was only the beginning.

A few days later, Brown rode into an Aboriginal camp and he opened fire. Bidgidanga and the far-north became a place of mourning. When blacks killed whites it’s seen as an outrage. But punitive parties like the one led by Maitland Brown, are seen as justified and legal and necessary. And that’s telling us a lot about the way that frontier violence functioned in colonial Australia.

And were these killings unprovoked? Let’s look at Panter’s own testimony. Here he describes Aboriginal people as ‘niggers’, and vows to give them ‘a pass to Kingdom Come’. His racist account and those of other explorers reveal the actions and the attitudes that fuelled frontier violence.

SUSAN CARLAND: In the harsh environment of Australia, whites and blacks often competed for resources. And the scarcest resource in the north-west in summer is water. The explorers’ letters and journals describe the way they exhausted ‘native’ wells, draining them of water for their stocks and their horses. And finding the water was as great a source of conflict as stealing it.

BRUCE SCATES: Panter’s journal from May 1864 relates the way they captured and interrogated a so-called ‘native woman’, dragging her back to the stronghold of the camp as she spat and scratched at them.

And of course white men’s abuse of black women was another frequent trigger for violence on the frontier.

SUSAN CARLAND: Many of the so-called murders committed by Aboriginal people were payback killings, acts of revenge exacted in retaliation for injury. It’s also possible the explorers trespassed on a site sacred to Bigidanga people. The last entry in Panter’s diary describes how during the day natives visited their camp and regaled his party.

‘They kept whispering’, Panter wrote, ‘and making signs we could not understand’.

After a series of angry altercations, Panter fired his revolver. That was the final act in a history of provocation.

BRUCE SCATES: So the claims that are made by this monument, of these faultless white men martyred by ‘treacherous natives’, really don’t stand up to close historical scrutiny. Indeed, this monument is more about mythology than it is about history.

It’s about the way that Maitland Brown, his generation, and far too many generations to follow him justified the violent dispossession of Aboriginal people from their lands. But white Australians’ attitude towards that frontier war have changed – and those changes are reflected here, on this very monument.

SUSAN CARLAND: 1992 was a landmark year in Australia’s race relations. In June, Australia’s High Court handed down the Mabo judgment, settling a long-disputed claim over the ownership of the Murray Islands.

The Crown at last conceded that Indigenous peoples had lived in Australia for thousands of years and that they enjoyed rights to their land according to their own laws and customs. The historic Mabo ruling effectively overturned the doctrine of ‘terra nullius’.

And a little over a year later, elders from Bidgidanga unveiled a new plaque at the base of this memorial. It’s a history from the other side of the frontier, acknowledging the right of Aboriginal people to defend their land, the history of provocation that led to the explorers’ deaths and the murderous work of the punitive party that followed.

The plaque was placed here in memory of Aboriginal people killed at La Grange. And it commemorated all other Aboriginal people killed during the invasion of their country.

BRUCE SCATES: That extraordinary ceremony was witnessed by representatives of federal, state and local government. It brought together Indigenous people from across the state and across the nation.

We watched a performance of Noongar dancers from Pinjarra, the hum of didgeridoos echoing from Norfolk Pine behind us. The ceremony ended as Aboriginal people scattered dust from the site of the massacre and two white children came forth and laid wreathes of flowers decked in Aboriginal colours.

SUSAN CARLAND: In 1911, when the memorial was raised it was a monument to murder, enshrining the hatred that divided white and black history.

BRUCE SCATES: But in 1993, when this monument was remade, it became a symbol of reconciliation. ‘Mapa Jarriya-Nyaluku’ is now inscribed at its base.

SUSAN CARLAND: ‘Let us all sit down together in peace.’ Let’s end this episode where we began, at the Gweagal shield briefly displayed in the National Museum of Australia.

Just when this shield will return to this country is anyone’s guess. Taken without consent in 1770, some have even argued there’s a case for its permanent repatriation.

BRUCE SCATES: A shield can be read, as we’ve seen, as a potent symbol of conflict, of the frontier violence, the clash of cultures, that are erupted right across this continent.

But it’s also something equally significant, isn’t it? This shield protects its owner – and the ongoing connection that Aboriginal people feel to items of material heritage like this – remind us of the strength and the resilience of this country’s rich and diverse Indigenous cultures.

SUSAN CARLAND: Australians, black and white, are still connected to the events that took place on Botany Bay in the April of 1770, but perhaps this exhibition offers a way beyond that painful past, to a place of sharing and dialogue and understanding.

[TEXT]: At the request of Aboriginal community representatives in Sydney, the British Museum is undertaking further research into the shield.

Findings will be published when the process is complete.

BRUCE SCATES: If you’d like to learn more about the issues raised in this episode, why not catch ‘Susan Carland In Conversation’. This time Susan is speaking with Peter Yu in the First Australian’s Gallery at the National Museum of Australia.

Activities

1. How do the presenters tell the story of encounters between Aboriginal people and Europeans?

2. What evidence do they present to support their explanation of those encounters over time?

3. What is the explorer's monument in Fremantle, Perth, and how has it become associated with reconciliation?