‘We need radical and permanent change’

2012: Murray–Darling Basin Plan introduced

‘We need radical and permanent change’

2012: Murray–Darling Basin Plan introduced

Learning area

In a snapshot

The Murray–Darling Basin Plan is an historic agreement between the Australian Government and state governments to manage Australia’s largest river system in a sustainable way. It was first introduced through the Commonwealth Water Act 2007 and the creation of the Murray–Darling Basin Authority. Since then the plan has gone through a number of changes. It aims to strike a balance between preserving the river system and allowing water to be used by the people who live and work in the basin in a fair way.

Can you find out?

Can you find out?

1. What is the Murray–Darling Basin and how important is it?

2. What did the Murray–Darling Plan originally suggest and what was the reaction to it?

3. What was the main finding of the April 2020 report and what did it recommend?

Why is the Murray–Darling Basin so important?

The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest and most complex river ecosystem. It stretches from Queensland to New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Victoria and South Australia. It’s made up of about 77,000 kilometres of rivers and is home to about 2.6 million people.

For generations the basin has been the heartland for over 40 Aboriginal nations and it holds deep cultural, social, economic, environmental and spiritual value. The rivers support rich ecologies, including 30,000 wetlands, and many of these are internationally important.

In the 1800s colonial governments and settlers saw an opportunity to develop agricultural businesses and towns using these natural systems. Today agriculture is the biggest user of water in the basin and supplies up to a third of Australia’s food.

What happened to the river system in the 1800s and 1900s?

By the end of the 1800s irrigation pumping could divert the whole late-summer flow of the Murray River. In 1889 the New South Wales Parliament predicted potential ‘periods of no flow downstream’. Governments agreed to schedule irrigation-pumping so that people who lived downstream would still get water.

In 1914 the Prime Minister and the New South Wales, Victorian and South Australian state premiers signed the River Murray Waters Agreement to better manage water in the basin.

Numerous dams, weirs, locks, canals and pipes were built across the Murray River system. These allowed the river to provide water for irrigation and town water, and later for the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme.

But it also changed the timing, temperature and levels of water flow. Some wetlands dried and shrank while others were flooded, killing trees. The numbers of water birds, fish and other water wildlife dropped. This was made worse by soil erosion, over-grazing by farm animals, pollution and land-clearing. By the 1960s dryland salinity had become a serious problem.

Research task

The National Museum of Australia has a large collection of objects relating to the Murray–Darling Basin. Choose one and explain how it represents this defining moment.

Research task

The Paddle Steamer Enterprise operated on the Murray River for many years. Find out about its important role on the water ways.

In 1991 the Darling River had the world’s longest toxic blue-green algae bloom. Blue-green algae naturally live in rivers, lakes and waterways. But in certain conditions they can multiply quickly and form ‘blooms’, which can discolour the water, form scums, affect fish and reduce water quality. Farmer and poet Eric Rolls described this ‘flaring green ribbon’ as a distress signal. It highlighted the river system’s problems to politicians, landholders, environmental managers and members of the public.

‘For this plan to work there must be a clear recognition by all — especially by state and territory governments — that the old way of managing the Murray–Darling Basin has reached its use-by date.’

Why was the Murray–Darling Basin Authority created?

In 1994 the Council of Australian Governments, which managed matters of national importance or matters that need coordinated action by Australian governments, agreed to put a limit on how many people and businesses can draw water from the river. And in 2004 the states agreed to a plan for major reforms including sustainable water allocation.

By the mid-2000s a long drought had led to poorer water quality and showed how this would threaten livelihoods and ecosystems.

In 2007 Prime Minister John Howard announced a 10-point plan and promised $10 billion to make sure the basin was managed sustainably for Australia as a nation: ‘In a protracted drought, and with the prospect of long-term climate change, we need radical and permanent change. Without decisive action we face the worst of both worlds — the irrigation sector goes into steady but inevitable decline while water quality and environmental problems continue to worsen.’

The government passed the Water Act later that year, which created the Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA). The MDBA’s job was to prepare a plan to protect and bring back the basin’s environmental health.

Most of the $10 billion was to be used to help fund irrigation infrastructure. It was hoped that more efficient irrigation would result in more water flowing to the river environment.

What happened when the Murray–Darling Basin Plan was released?

In 2010 the MDBA released its draft Guide to the Proposed Basin Plan. The plan suggested that water entitlements — the right to own an exclusive share of water — would need to be cut by 3000 to 7600 gigalitres to ensure the health of the rivers.

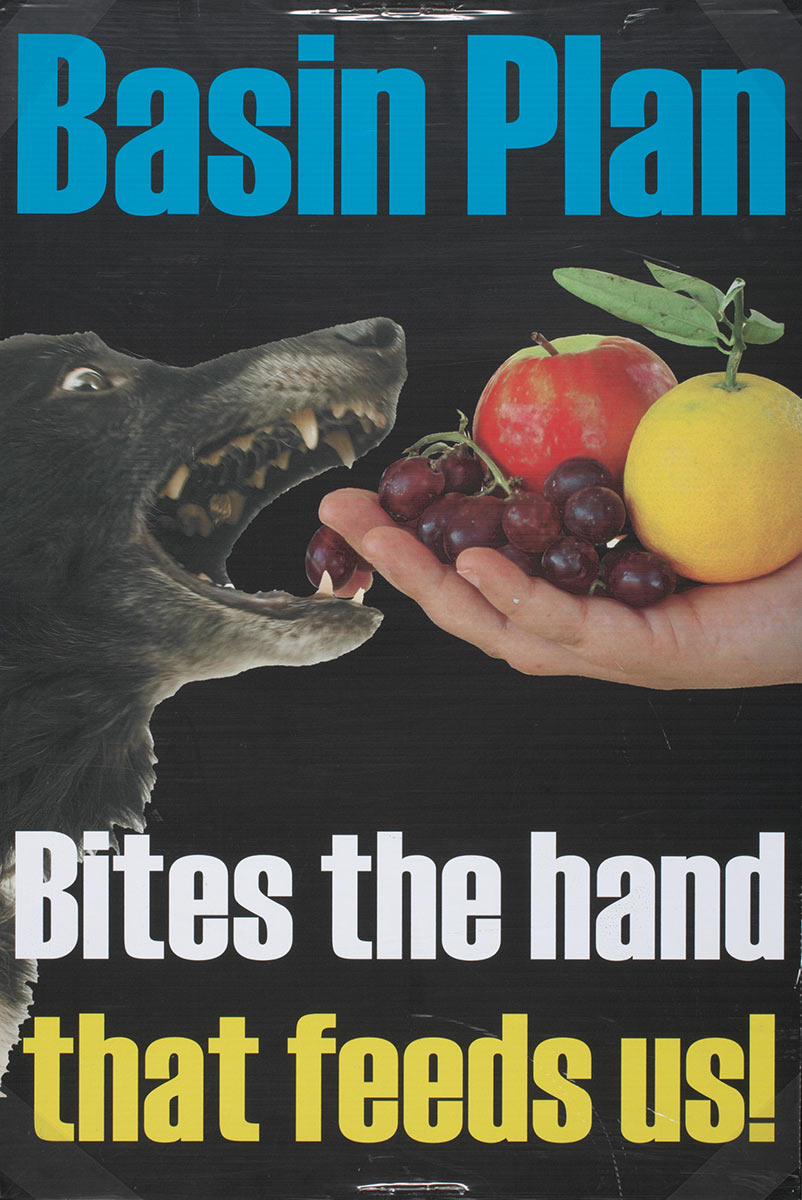

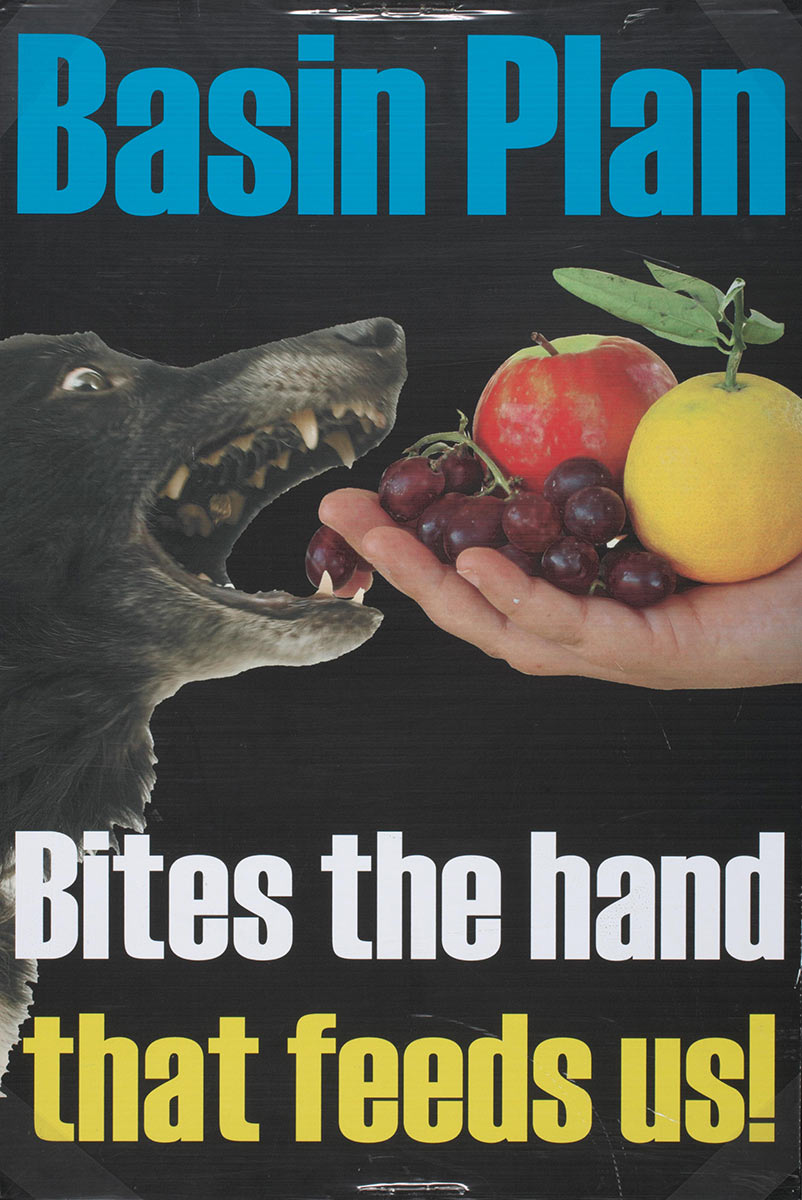

Communities who lived and worked in the basin became worried about how this would affect their livelihoods. Hundreds of people in major irrigation towns turned up to MDBA consultation meetings. In Griffith a group of irrigators burned copies of the guide, which made national news.

The MDBA Chair resigned and the government ordered an inquiry. The new Chair, Craig Knowles, announced a revised plan: ‘The result should … have regard for the people who live in the Basin, their lives and livelihoods.’

The final plan, passed in Parliament in 2012, set a lower target for reducing water entitlements by 2750 gigalitres. It also didn’t take into account future climate change.

‘A more unified Basin-wide position and plan of action for Basin Plan implementation is required across all levels of government to improve leadership in the Basin and address the current crisis in confidence.’

What is the situation now?

Different groups still argue about whether the Murray–Darling Basin Plan is the best plan for bringing back the health of the river system.

In 2018 a group of leading Australian scientists, economists and water policy experts stated, ‘Australia is paying the price of alleged water theft, questionable environmental infrastructure water projects, and policies that subsidise private benefits at the expense of taxpayers and sustainability’.

In 2019 investigative journalists uncovered scandals, including claims of corruption. After this the states agreed to review the Murray–Darling Basin Plan. A report released in April 2020 said that the amount of water in the Murray River system was only about half of what it was in the previous century and that the frequency of dry years has increased because of climate change.

Read a longer version of this Defining Moment on the National Museum of Australia’s website.

What did you learn?

What did you learn?

1. What is the Murray–Darling Basin and how important is it?

2. What did the Murray–Darling Plan originally suggest? Was this accepted?

3. What was the main finding of the April 2020 report and what did it recommend?