Learning module:

Law and democracy Defining Moments

Courts making law

3.3 Taking Mabo further — Native Title Act and the Wik decision

The Mabo case created the new concept of ‘native title’ rights under Australian law. But it only applied to the five people who won that case.

When the High Court makes a decision that breaks new ground it creates a precedent. Later this precedent can be applied in similar cases. But this is a slow way of applying new legal principles, as courts can only hear a limited number of cases and it is expensive for individuals and groups to take a case to court.

An alternative and potentially far quicker solution is for the Australian Parliament to pass legislation that covers the principle of the Court’s original decision so that it applies throughout Australia. This is what the Australian Government decided to do with regard to native title.

Native Title Act

The Mabo case had established the principle of native title in Australia, and the next year the Native Title Act 1993 was passed. The Act declared that where ‘Crown land’ (land owned by the government) had not been ‘alienated’ (sold to someone) and an Indigenous group could prove their traditional and continuing physical and cultural association with the land, then that group could claim ‘native title’ to the land.

If the land had been alienated, and the owner held that land in freehold — that is, had the legal title deeds of ownership — then there could be no native title claim to that land. That meant that there could be no native title claim on houses, shops, factories, buildings, parks, sporting grounds, schools, shops, farms and so on.

However there was another type of land holding: not Crown land, and not freehold land, but ‘leased land’ — that is, Crown land rented to someone, usually as pastoral land, for a set period, a set payment and with set restrictions on how it could be used. Did native title apply there?

Another case answered this question.

The Wik case

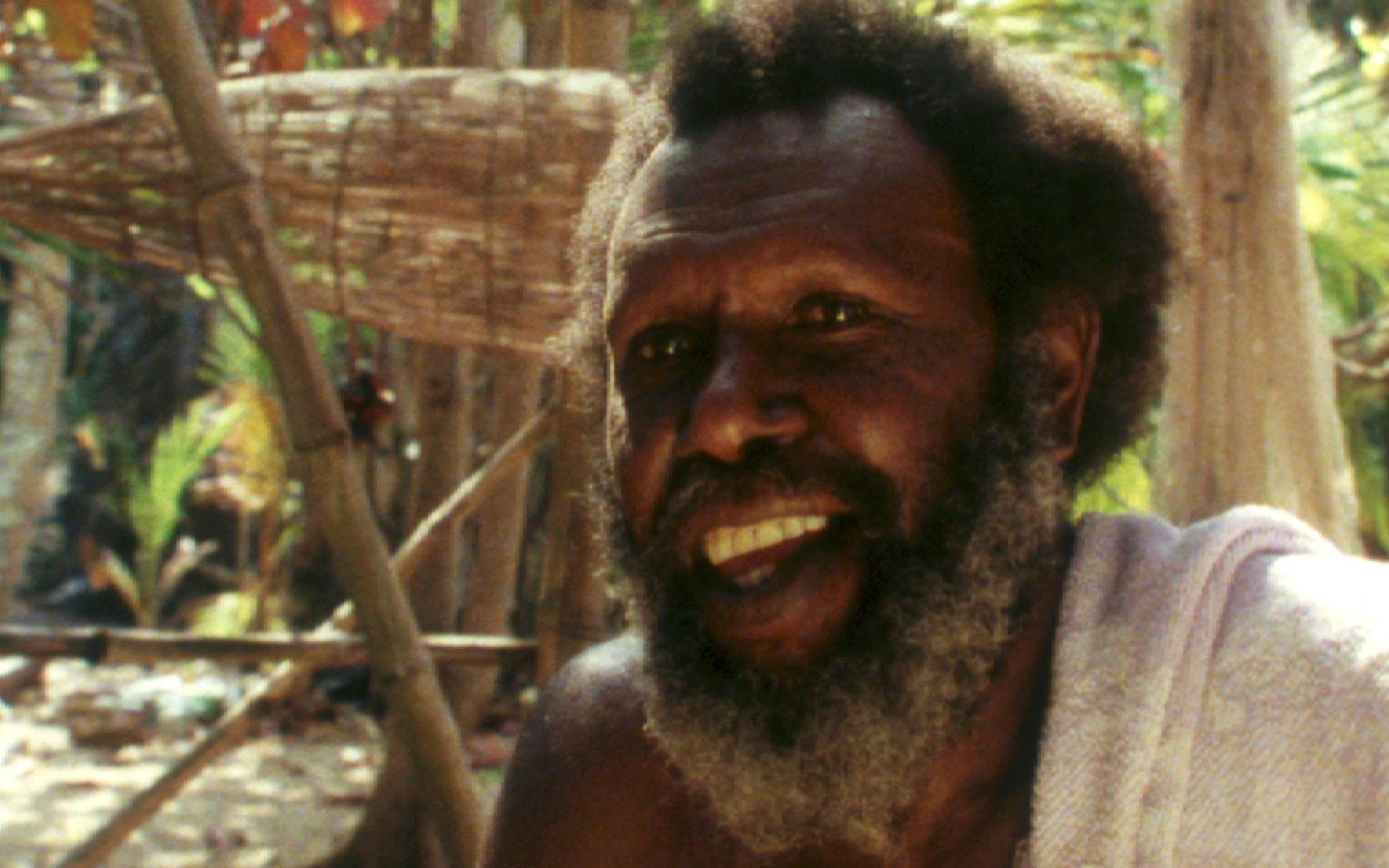

The Wik people live on the western side of Cape York Peninsula in the far north of Queensland. Their traditional land is the area between the Archer River and the Edward River.

The Queensland Government had issued pastoral leases and a mining lease in the area, and had then declared it a national park, with the pastoral and mining leases able to continue operation within the park.

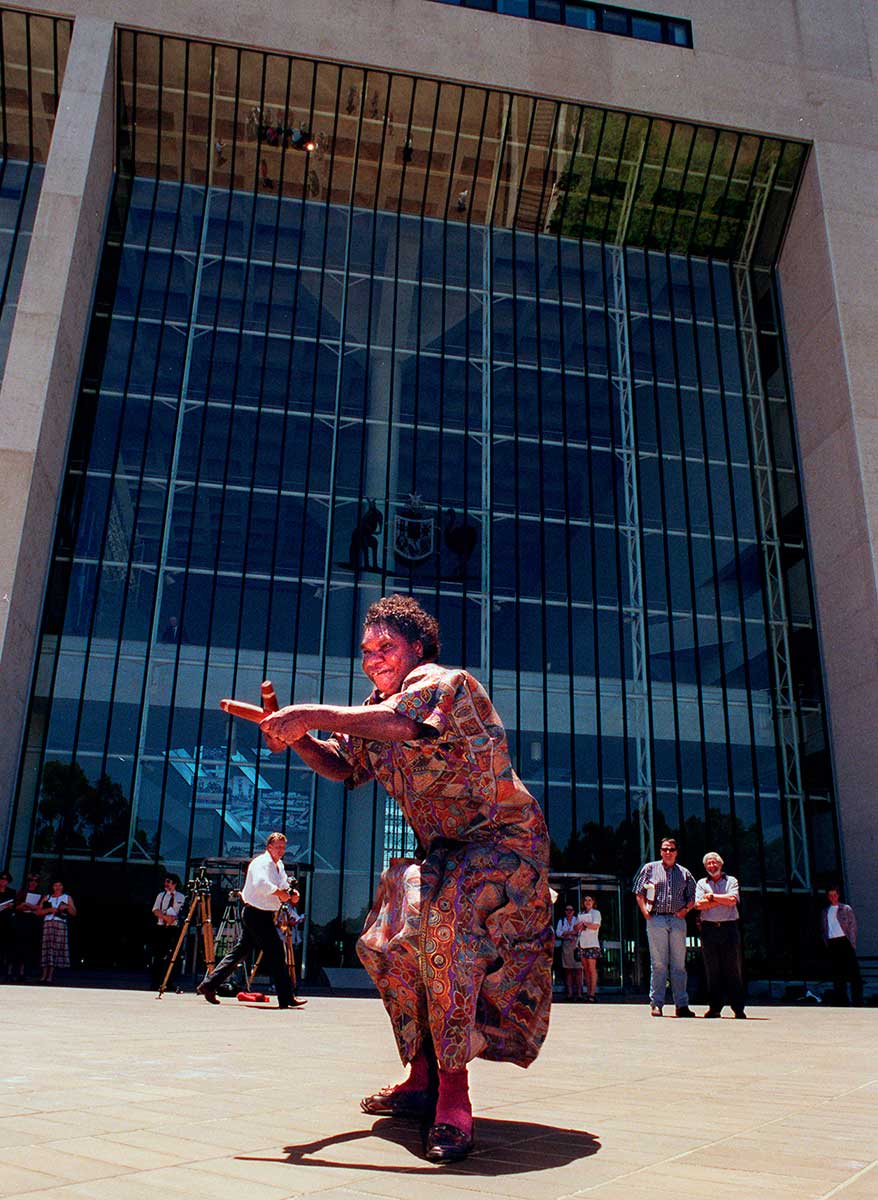

The Wik people claimed in 1993 that the land should be theirs under native title. The case eventually reached the High Court in 1996. The High Court had to decide if leases extinguished the Wik people’s native title claim.

The Court decided 4:3 in Wik Peoples v Queensland in favour of the Wik people. Their decision meant that there was a new category of native title, one that created shared rights to an area between the person holding the lease and the traditional Indigenous owners. Both could exercise rights to the area as long as the exercise of one did not conflict with the rights of the other. For example, a pastoral lease holder could dig a dam to provide water for the cattle, but not if that dam desecrated a sacred place. On the other hand, the Wik people could hunt for food but would not be able to remove fences in order to give kangaroos greater access to food or water.

As with the Mabo case, the decision of the High Court of Australia only affected the Wik people who brought that case to court. It could not be applied to other cases unless those cases were also brought to court and were also successful.

The solution to this problem, as it was in the Mabo case, was for the Australian Parliament to pass legislation which could then be applied to the whole of Australia. This involved amending the Native Title Act 1993.

After a great deal of debate and controversy, the Australian Government came up with a 10-point plan that they believed gave certainty and security to both lease holders and Indigenous traditional owners. In particular the plan aimed to establish that where there was conflict between the two uses of land, the rights of the lease holder were prioritised.

1. What did the High Court have to decide in the Wik case?

2. What was the new category of native title that the Wik case established?

3. According to the 10-point plan, if there was conflict between the two uses of land, whose rights were prioritised?

The High Court and the Mabo and Wik cases

The two sources below explore the role of the High Court in the Mabo and Wik cases. Read them carefully and answer the questions that follow.

Source A

Robert Orr, On the 25th anniversary of the Mabo decision:

‘I do not want to oversimplify the complex legal history of Australia, but I think it is clear that the law played a significant role in the racially discriminatory treatment of Indigenous Australians from 1788, including in the foundational principle that from settlement their laws and rights under them were not recognised.

‘The Mabo [No.2] decision, and the Native Title Act, have revised this legal principle and recognised and protected the native title rights of Australia’s Indigenous people. These developments have importantly involved an acknowledgement of regret for this aspect of our history and the law’s role in it, and transformed Indigenous Australians, who had to a large extent become outsiders in our society, into the holders of extensive property rights and significant legal and political voices.’

Robert Orr, ‘Australian Government Solicitor No. 3’, AGS Magazine, https://www.ags.gov.au/publications/agsmagazine/Issue3-HTML/Robert-Orr-Mabo.html, viewed 25 August 2020

Source B

A constitutional lawyer, George Williams, on native title:

‘The Mabo case gave rise to great expectations and fears. Some people produced maps showing how swathes of the Australian continent would be transferred into Aboriginal hands. Others foresaw that the courts would recognise further Aboriginal rights. None of these has occurred.

‘One reason for this is that the High Court has refused to extend the Mabo decision. Soon after, Chief Justice Sir Anthony Mason rejected any notion that Aboriginal peoples were sovereign nations. Native title existed only because these rights were recognised by the law of the colonisers. He also rejected an attempt to recognise the customary criminal law of Aboriginal peoples.

‘Native title … is hard to prove. The High Court has said that a claimant must show a continuous observance of traditional law and customs since the British arrived. However, the dispossession and dispersal of Aboriginal peoples can make this impossible, meaning that native title rights have been lost.

‘A quarter of a century on, Mabo was a necessary and important step in our development as a nation. It forced us to confront the convenient fiction upon which Australia was built and lands taken for development. The decision has brought about important processes of agreement making, and enabled a new generation of Indigenous leaders to come to the fore.

‘However, the case has not proved to be the panacea that many had hoped. It has not borne out the inflated expectations of the time, with native title often proving elusive and no further rights beyond land being recognised.

‘One legacy of the Mabo case has been to shift the debate back to the political realm. For the time being, there is little appetite in the courts to further develop Aboriginal rights. Given this, it is no surprise that Aboriginal people are instead seeking justice and political empowerment through constitutional change and negotiated agreements such as treaties.’

George Williams, ‘The ongoing legacy of the Mabo decision’, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 June 2017, https://www.smh.com.au/opinion/the-ongoing-legacy-of-the-mabo-decision-20170602-gwj2p4.html, viewed 25 August 2020

4. Identify and compare the arguments provided in Source A and Source B about the social impacts of the Mabo and Wik cases. What do they agree on? What do they disagree on?

5. In what ways do you think Australia can create more meaningful change with regard to native title?

6. Describe the role of the High Court in the Mabo and Wik cases and how it changed native title law in Australia.

7. How does this Defining Moment help you understand the role of the High Court in Australia?