Learning module:

War correspondents

War correspondents

37. The aftermath

You make your way to the University of Melbourne, a complex of large stone buildings just to the north of the city centre. You have an appointment with a lecturer at the Workers Educational Institute, Dr Ella King.

She takes you to her classroom.

‘Great timing. I’ve just finished a lecture about the outcomes of the Great War.’

She gestures to the blackboard where lines of notes are written up.

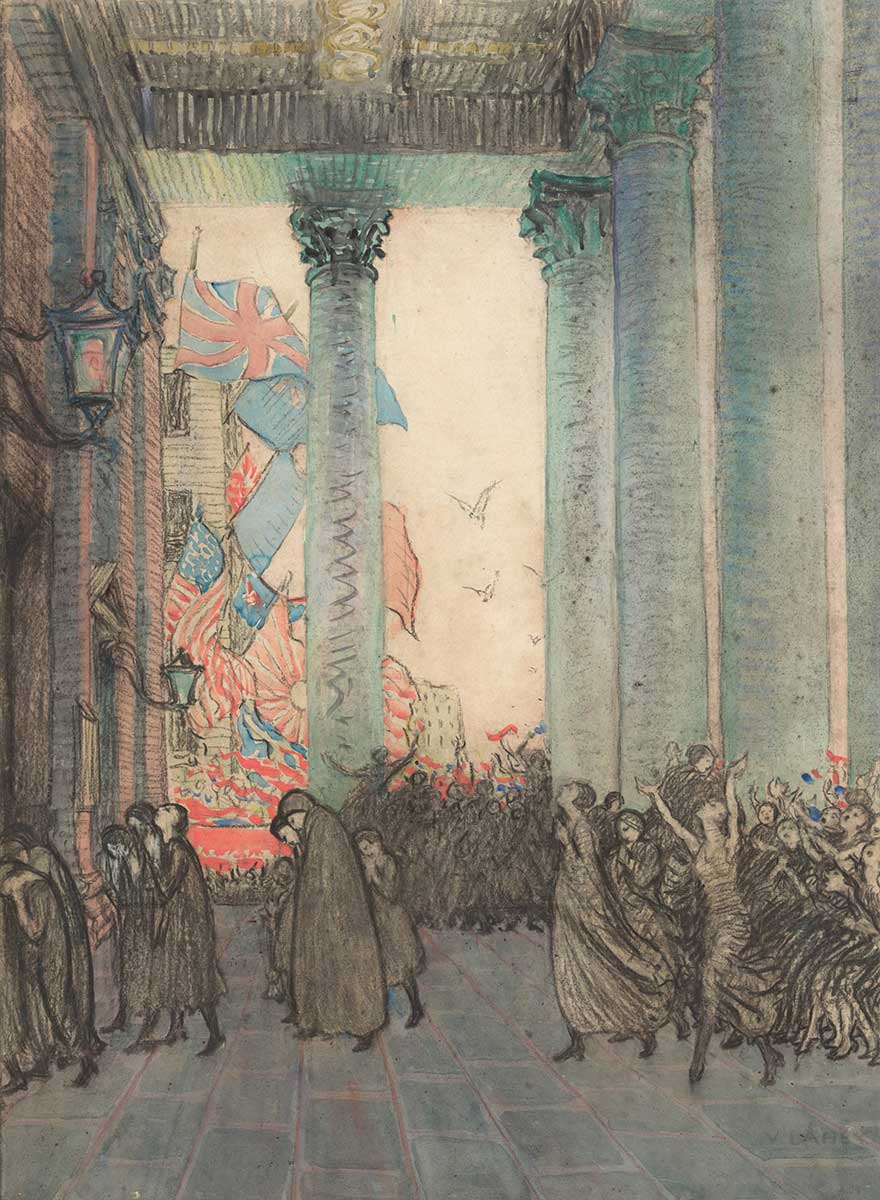

‘There were many complex and contradictory effects of the war. Women’s roles in society increased. They began occupying public roles they hadn’t held before and mobilising politically — for and against conscription for example. Very few took on men’s jobs when they went off to fight, but many of them became part of a vast volunteer workforce that was crucial to the war effort.’

She walks over to another part of the blackboard and points at some notes.

‘The war forged a national identity for Australia, especially the Gallipoli campaign and the legend of the Anzac soldiers. But great social divisions — all too evident before the war — worsened more than anyone could have imagined. Many returned soldiers saw the war as a great victory, while trade unionists saw the war as a great waste of time and resources. Many felt this war was a conflict between big empires, where leaders sent ordinary men to their deaths.

‘There has been a big increase in government control over public life. During the war the government controlled the media and used propaganda to try to tell people how to think about it. Propaganda is information that is sometimes misleading or exaggerated, used to promote a cause. In this case the government used it to make people think the war was a good idea. Taxes also went up a lot to pay for the war effort.’

She rubs out some of the notes and looks at some others.

‘Ah yes, the figures. Australia had the most casualties per head of population of any of the Allied nations. And the long-term cost, well ... the medical care and benefits paid to returned soldiers cost the government a lot and made it poorer. By 1932 over 280,000 returned soldiers were receiving money from the government.

‘There were some economic benefits though. Australia developed light industry and more mining operations. Australia had to be more self-reliant as the Europeans went to war with each other. This meant that Australia had to produce things they previously would have got from overseas.’

She pauses, deep in thought.

‘The impacts were long lasting: thousands of dead men, damage to the economy. Women worked in an increasing range of roles outside of the home. Australia became a little bit more independent from Britain (although we still depended on the old country as a major trading partner).’

‘Finally, during the peace talks, Australia made sure that there was no statement about racial equality included in the peace agreement. The White Australia policy was alive and well.’

She looks back at you. ‘I hope that answers your questions.’

You thank her for her time.

Your task

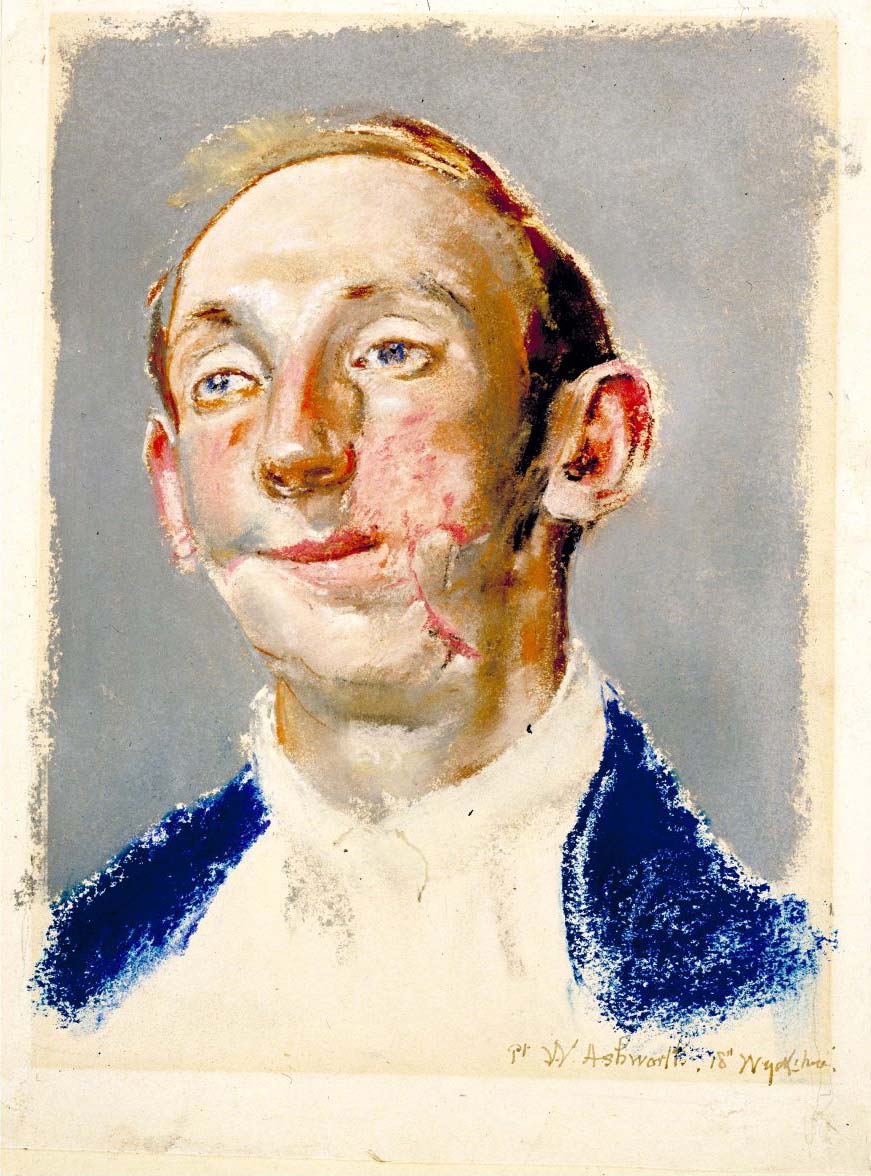

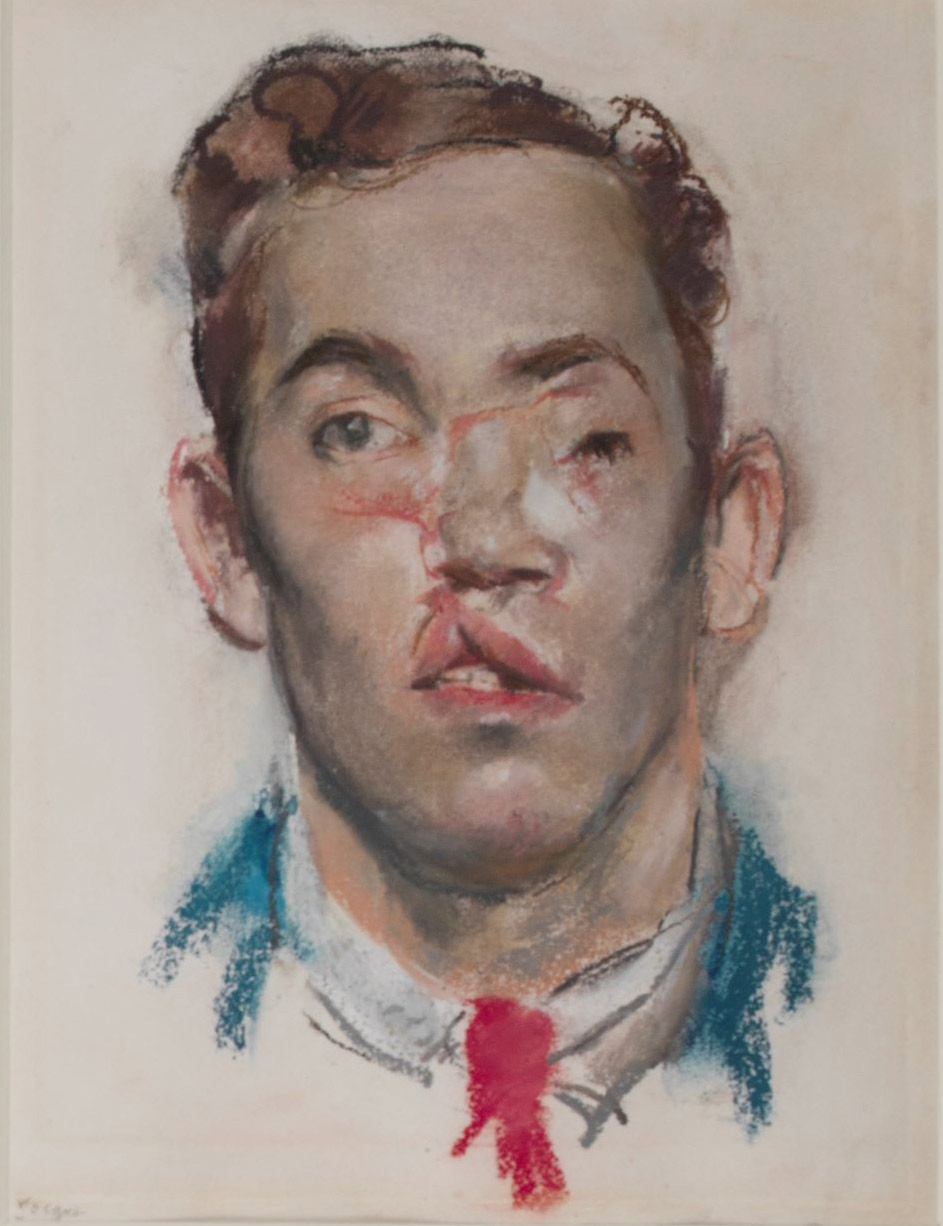

Before you leave the university, you decide to visit a medical facility to find out about the treatment of men who have suffered facial injuries in the Great War. A doctor who served in London has brought some portraits from Britain that were used to help surgeons with facial reconstruction. You contact Mr Callister and suggest that photos of some of these portraits with some commentary would be a great addition to the special war issue. He agrees and sends down a photographer.

The photographer, Ruby Irvine, also happens to be an expert on using outside knowledge to help understand historical sources.

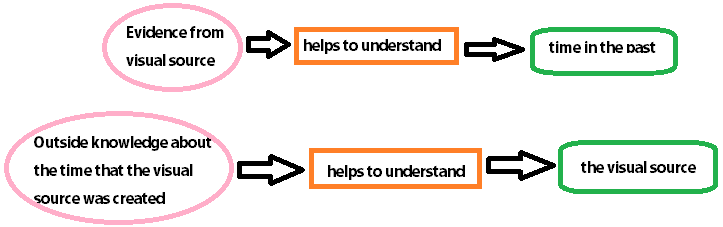

‘A visual source can tell us a lot about a time in history. We can also use knowledge that we have about a period in time to help understand a visual source. There are two different skills that you could use here. Consider this diagram...’

She draws this on a piece of paper she has in her bag:

‘What we are talking about here is the second one — using outside knowledge to help understand the source.’

‘Now, obviously, the first thing you need is some knowledge about the time period. If you don’t have that, you can’t use this skill. Once you’ve got that knowledge, think what part of it is relevant to the visual source you are looking at.’

Look at the two portraits below and complete the table.

| Feature of the source | Sentence showing how outside knowledge helps explain the source |

|---|---|

| Injured faces | |

| Both images are of men | |

| Facial expressions |

You complete your analysis, thank Ruby for the photos and the guidance, and submit the article back to the head office.

Back at the office, Mr Callister says ‘I’ve got some friends from the war. Men who volunteered while I stayed here and just wrote about it. Should I feel ashamed? I don’t know. Anyway, I would like you to go and interview these men for me. They’re Anzacs. Survived Gallipoli. Get something interesting, but mostly, show respect.’

He looks at you sternly. You assure him you always show your sources respect, and get the tram to the city centre, where you are meeting his mates in a pub.