Australian Journey Episode 01: Travelling Country

Indigenous and European perceptions of the Australian landscape, focusing on Burke and Wills’ tragic journey of exploration.

View transcript

+ -SUSAN CARLAND: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this series may contain images, voices or names of deceased persons.

BRUCE SCATES: This episode, Travelling Country, is part of the series that looks at the land. It focuses on Burke and Wills’ tragic journey across the Australian continent.

We’ll explore the differences between Indigenous and European perceptions of the landscape. We’ll begin in Canberra and we’ll end at a striking statue in the very centre of Melbourne.

SUSAN CARLAND: I’m here today in the single most important gallery of the National Museum of Australia. These amazing spaces capture the experience of the First Australians – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We’re surrounded by sculptures and images that welcome us onto Country, Ngunnawal land, and I’m here today to try to imagine this Country through Indigenous eyes.

In another part of the gallery, we will find one of the largest pictures of the Great Sandy Desert ever to be painted. It’s a remarkable collaboration between 19 Traditional Owners, capturing the form and the spirit of the land.

It’s beautiful, isn’t it? This canvas just explodes with light and colour, but it’s also a kind of map. Like so much Aboriginal art, Ngurrara I offers an aerial view of the landscape – that great black line signifies the Canning Stock Route; spiralling circles reveal the location of water holes, and you can even see the paths of where animals walk. You can sense the presence of ancestral beings that carved out every feature of this landscape. This canvas is encoded with knowledge, the knowledge Aboriginal people acquired over countless millennia. And yet it also serves a very contemporary purpose.

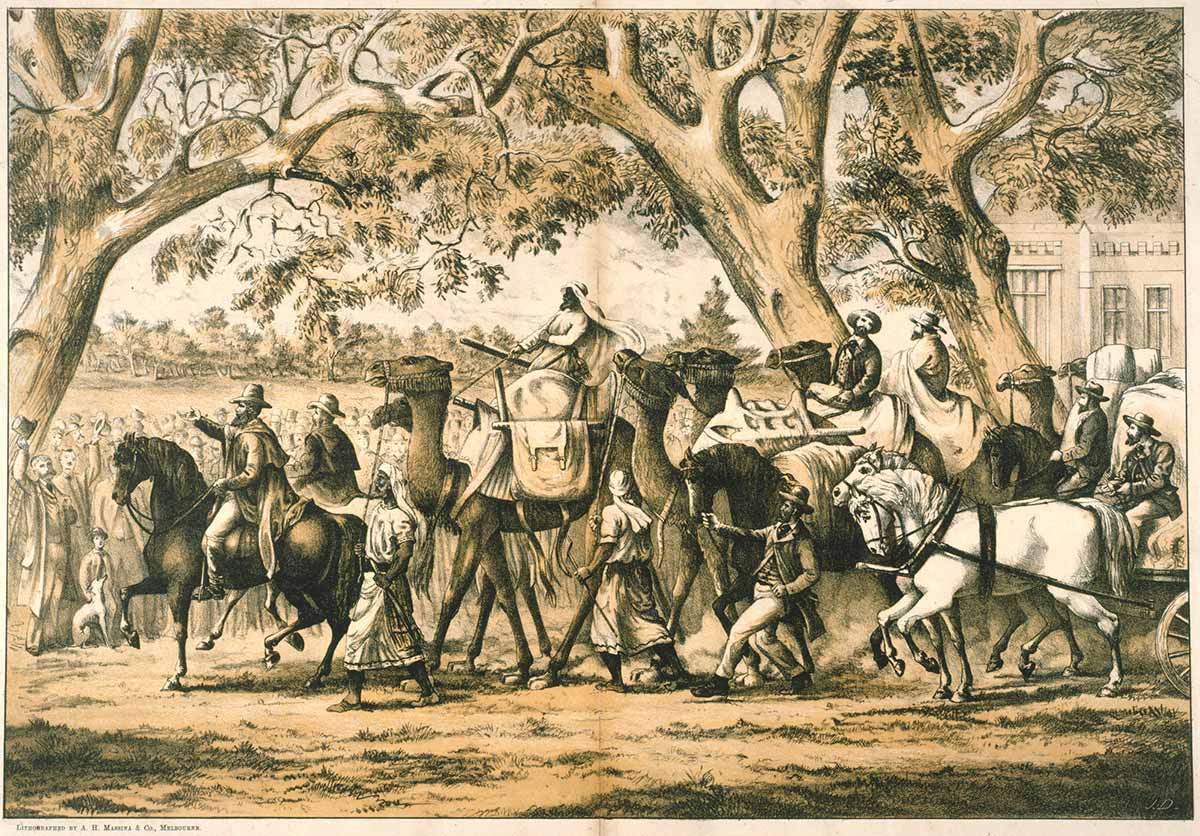

Ngurrara I demonstrates Walmajarri and Wangkajunga peoples’ enduring attachment to this Country and it was part of a successful land rights claim in 2007. Art like this was both cultural and political – it affirms an ancient connection to country and asserts an urgent sense of sovereignty.

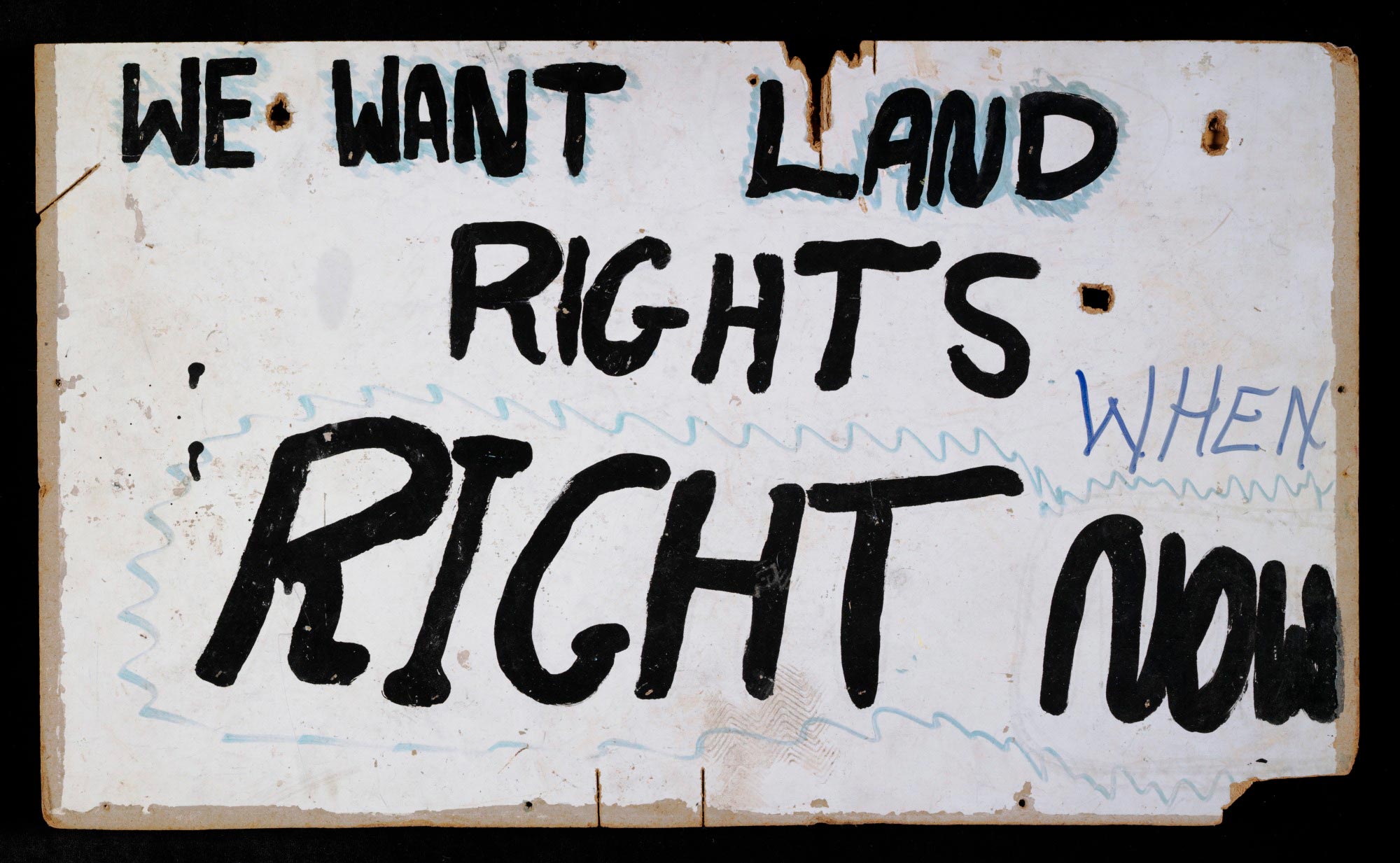

BRUCE SCATES: You might compare that way of seeing the landscape, with this one. I’m in a special repository of the National Museum and this map, dated 1861, charts the route of the Victorian Exploring Expedition. That expedition crossed the continent, from south to north, 3,250 kilometres, all the way from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Now, that Aboriginal knowledge of the Great Sandy Desert was vast, but it was intimate. In walking and singing the land Indigenous people tended every corner of their country. These straight lines that cut across the landscape – they’re very different, aren’t they?

Crossing the continent was a search for new sites for settlement. European men and their cattle would occupy what they liked to call the ‘empty heart’ of Australia. And mapping the land like this, well, that was actually a way of possessing it. It subjected those curving contours of the landscape to a colourless geometry, a very Western sense of order.

Most important of all, you note the way that the explorers name each place as they discover it – even though those places had been named, they’d been explored, they had been mapped by Aboriginal people long, long before them.

Ngurrara II [sic] served a political purpose, sure, but so too does this ostensibly scientific document. Maps subverted and they displaced older understandings of the land. They were part of the process of colonisation. And renaming country, after English kings and queens, rendered the sovereign people of this land invisible – or rather, it tried to.

SUSAN CARLAND: Both Ngurrara I and the Victorian Exploring Expedition’s map are priceless historical documents. Imbued with deep cultural significance, they number amongst the many treasures of the National Museum of Australia. Both objects convey separate and distinct views of the land and yet they are engaged in a kind of conversation, a dialogue, if you like, between Indigenous peoples and European invaders.

Europeans spoke of land as if it were a kind of commodity, something you could possess, trade, place a simple monetary value on. The Aboriginal understanding is very different. Walmajarri and Wangkajunga didn’t own the land, the land owned them – they were, and are, a living part of it.

BRUCE SCATES: In this episode we retrace the steps of the Victorian Explorers Expedition. Led by Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills, it remains one of the most tragic and one of the most compelling narratives of Australia’s white colonial history.

Both of those men died in that attempt to cross the continent and those deaths elevated them to a kind of legendary status. But the story of Burke and Wills is much, much bigger than that. It too is about ways of viewing the landscape, Indigenous and outsider understandings of the country.

And to take up that story, we go to where the Victorian Explorers Expedition began – the city of Melbourne.

SUSAN CARLAND: Here the two explorers look out over the city. Burke, the standing figure, looks like he’s plotting a route through the tram tracks. Erratic and quick-tempered, it was his misdirected leadership that ended in disaster. Wills, the expedition’s astronomer and navigator, holds a map in his hands, symbolically charting their way across the continent.

BRUCE SCATES: Monumental art like this told a heroic story. These two great men occupied this civic space in the same way that they mastered the interior. But did they really?

SUSAN CARLAND: A series of plaques circles the base of this monument and reading between the lines they tell us a very different story.

There are 19 men in the expedition, but few have any experience of life in the bush. Six wagons carry vast quantities of food and over 20 tonnes of equipment. Aboriginal people travelled lightly and lived off the land, but these heavy wagons were bogged down in the mud within miles of Melbourne.

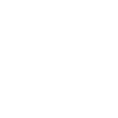

BRUCE SCATES: Even the innovation of those camels was something of a disaster. Acclimatisation societies were all the rage in colonial Australia. Amateur zoologists introduced one species after another, determined to improve – and that usually meant Europeanise – the landscape.

Some 26 seasick camels were eventually landed in Melbourne from India. ‘Ships of the Desert’, the Royal Society called them, but there was just one problem with this. The desert Burke and Wills traversed was nothing like the rolling sands of the Sahara. Sharp rocks littered the plains of inland Australia. Soon the feet of these poor ungainly creatures were cut to pieces.

SUSAN CARLAND: Working with those camels posed another challenge. The expedition recruited three ‘Afghan’ cameleers from the northern frontier of India. It was their skill, their labour, that guided that jolting caravan across the desert.

And that’s telling us something very important about the character of early exploration in Australia. Burke and Wills were hailed as very British heroes and yet the Victorian Exploration Expedition had a distinctly cosmopolitan character. The party included Germans, Scots, Irish and Americans and their faiths were just as varied – Protestant and Catholic, Hindu and Muslim. The infant colony of Victoria, a distant outpost of Empire, harboured this kind of cultural diversity and in time Indian and Afghan cameleers would carry goods to every corner of the continent.

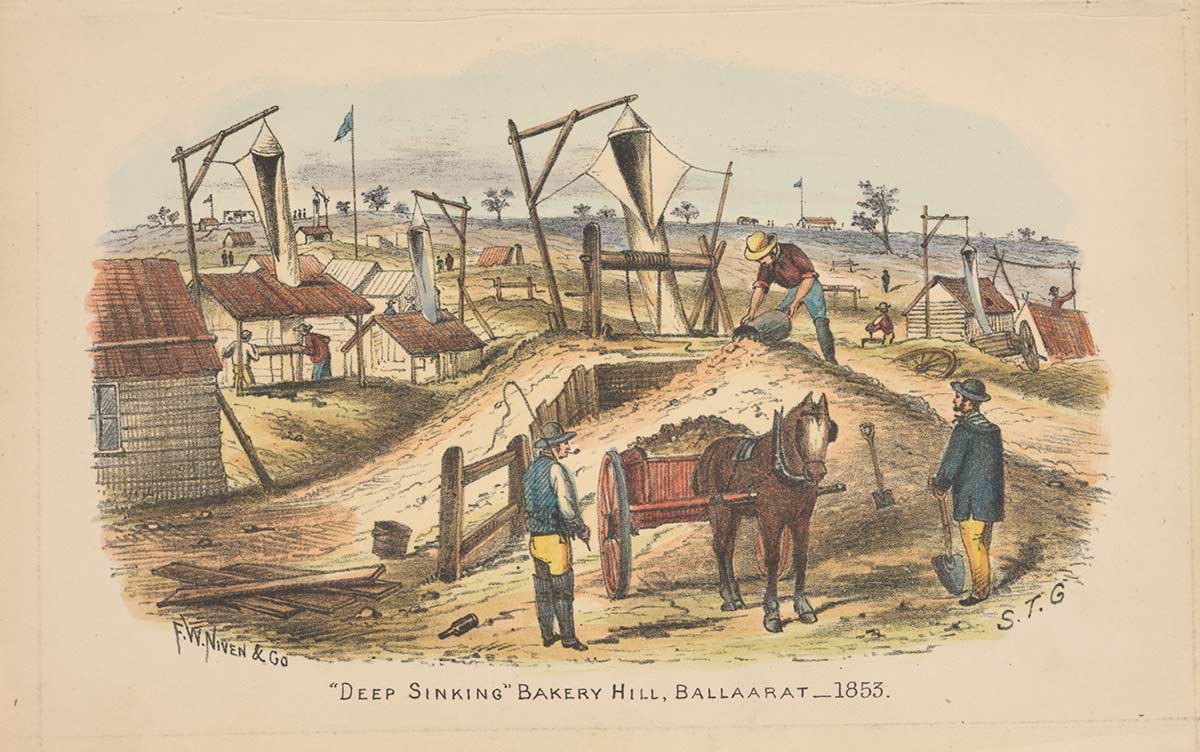

BRUCE SCATES: 86 days into the expedition the party reaches Cooper’s Creek. This is the furtherest-most [sic] point of European exploration and there, there Burke faces a choice. Now a cautious man would wait for the stores to come up, wait for cooler weather, but determined to be the first to cross the continent Burke, Wills, Charles Gray and John King make a mad dash, a mad dash to the Gulf of Carpentaria. It’s over 500 miles away.

They travel in heat of up to 50 degrees Celsius. Gray dies, probably of dysentery, on the return journey – it takes a whole day to bury him.

This plaque captures the moment those three survivors return to Cooper’s Creek – the depot had been abandoned within just hours of their actual arrival. Beneath the tree marked ‘DIG’, they find a few weeks’ rations. They’re exhausted, they’re malnourished, and they are on the very edges of survival.

SUSAN CARLAND: This same scene is captured in one of the many paintings that came to memorialise the expedition. It cost a thousand pounds and was the largest and most expensive painting ever to be hung in the National Gallery. A magnificent canvas it might be, but it is very poor history. Cooper’s Creek is seen here as an arid wasteland. The earth has been baked dry and the moon rises eerily over a parched and hostile land. In fact, this landscape looked nothing like this.

BRUCE SCATES: In the April and May of 1861, this place was little short of an oasis. The creek had left a series of billabongs, a source of deep, reliable water that attracted bird and wildlife for miles around. Those water holes were full of mud crabs and fish, what Aboriginal people would call ‘bush tucker’. Burke and Wills die partly of exhaustion and malnutrition, but they starve in a land of plenty, with food all around them.

Who had the knowledge to survive in the bush? It was Aboriginal people.

SUSAN CARLAND: This is nardoo. It’s a kind of native fern and it was a part of a staple diet of the Yandruwandha people. These rare specimens were gathered from Cooper’s Creek by the same expedition sent to find the explorers.

Each day, crawling on their hands and knees, Burke, Wills and King plucked a few billies [full] of fern from the earth and ground the seed into flour. ‘Anyone can grind nardoo’, they assumed, ‘anyone can make a damper and bake it’.

BRUCE SCATES: But Aboriginal people don’t just harvest nardoo. They sift it, they wash it, and they winnow it, and in doing so they remove the thiaminase that’s toxic in that raw plant. In the 19th century we assumed that Burke and Wills died of malnutrition and exhaustion – but in fact they probably poisoned themselves.

It’s the failure to learn from Aboriginal people that seals the fate of the explorers. Burke refused to let them anywhere near the camp, despite the gifts of fish and birds occasionally left for them. Most important of all, he misreads their knowledge of the land. So European arrogance, not Aboriginal neglect, claims the lives of the expedition’s leaders.

SUSAN CARLAND: The final bar relief shows King, the sole survivor, being rescued by a new exploration party led by Alfred Howitt. Here we see Howitt extend that Christian hand of friendship to a lonely man lost in the wilderness. But look at where King is sitting. He’s in a so-called ‘native’ shelter and indeed, since Burke and Wills’ death, he had been cared for by Aboriginal people. This image of solitude is at total odds with reality.

BRUCE SCATES: Perhaps it says a great deal about 19th century Australia — that men who blundered unprepared into the outback, who broke every basic rule of survival, who refused the great kindness of Aboriginal people, and who starved, and who poisoned themselves in a land of plenty — that they could be reimagined here as some kind of heroes.

SUSAN CARLAND: It says much about colonial Australians’ failure to understand this country and the sheer temerity they had to claim that land as their own.

BRUCE SCATES: And yet this rather overstated statue isn’t the only legacy that Burke and Wills have left us. In the midst of all this tragedy there is something wonderful and something visionary.

SUSAN CARLAND: And we can find it just a stone’s throw from here in one of Australia’s oldest and most distinguished libraries.

BRUCE SCATES: This is the Heritage Reading Room in the State Library of Victoria, and this – this is a collection of Ludwig Becker’s watercolours. Becker was one of the naturalists seconded to join the Burke and Wills expedition. At 52 he’s the oldest member of the party, and he was born and trained in Germany. Men like Becker, writing one learned paper after another, laid the foundations of scientific inquiry in the colonies.

Becker doesn’t cross the continent. In fact, he’s left stranded in Menindee, but his achievement is so much more significant. Becker’s watercolours and natural history drawings are a treasure, and they offer us a new way of seeing the landscape. Let’s have a closer look at them.

SUSAN CARLAND: It’s a watercolour: Indian ink on cream-coloured paper; it was completed 17 miles north of Lake Doroodu in February 1861.

You can see how attentive an artist Becker is. Beneath a detailed sketch of this lizard there are equally detailed notes on its behaviour and its appearance. And even the notation gives you a sense of Becker’s excitement.

‘I caught this fine lizard in the midst of a desert-like plain; it was running very swift over the sand. The drawing,’ he adds, ‘is of natural size’ and ‘the colours are taken while the specimen was alive – the beauty of them is gone after death’.

BRUCE SCATES: Beauty. In the 19th century, very few Europeans saw the beauty of the desert, especially where Becker was that particular day – on a waterless and treeless plain, with heat soaring into the 40s, even the lead melting in his pencil.

SUSAN CARLAND: Becker’s meticulous sketches suggest an interest in the desert for itself and all the varied organisms it sustained. They are an inventory of every living thing: plants, birds, the snakes that crawl across the open plains, the fish that swam in every water hole. Becker’s desert is a place teeming with life, not the impoverished place Europeans imagined.

BRUCE SCATES: The conventional European view of the interior saw it as somehow empty. Becker opens our eyes to the varied wonders of this arid world: its sheltered billabongs; its mallee sand cliffs; its ancient low-lying ranges worn down by the millennia of wind and rain; and the great floor of an inland sea that once stood in the heart of the continent.

SUSAN CARLAND: This is a new view of the desert but it’s also a new view of ourselves.

In Becker’s brilliant study of a mirage, the shape of the emus and dingoes is clear, and in the foreground, – not so the shadowy form of the men on their camels in the centre of that shimmering plane. And perhaps that’s a comment on the explorers’ alienation from the land they had set out to conquer. The desert is vast and it is ancient: it will last forever. The men here are clumsy intruders, fragile ephemeral, ghost-like.

BRUCE SCATES: It’s the people who truly knew and loved the desert that merited Becker’s special attention. This is a portrait of an Aboriginal man near the Darling River. He’s more suitably equipped than any of those European explorers. That digging stick will find water in a dry creek; it’ll crack open the skull of a lizard; that net will scoop up fish from the deepest billabongs; those eyes know every contour of the country.

SUSAN CARLAND: Becker’s journey, far more than Burke’s, was a voyage of discovery. He respected Aboriginal place-names, took note of their words, recorded their songs, sought out their company. And his paintings remind us of that same deep cosmology inscribed in the Ngurrara canvas.

BRUCE SCATES: We thought this would be a nice image to end on. It’s entitled, ‘Meteor seen by me on October 11 at the River Darling’, 1860.

In an age before science was divided up into hundreds of specialised fields, men like Becker practiced what was called ‘natural history’: he was an astronomer, a botanist, a geologist, an artist, a mapmaker. He was a truly Renaissance man and a man willing to learn from others.

SUSAN CARLAND: And just as the comet lights up the night sky, Becker’s sketches and diaries illuminate the dark tragedy of the Burke and Wills expedition. They show us the marvel of the desert, not just its terrors; they remind us that the centre is not a ghastly emptiness, an obstacle to be crossed, but a place of breathtaking beauty.

BRUCE SCATES: Becker, like Burke and Wills, was a victim of this ill-fated venture. He died, probably of scurvy and exhaustion, in a vain attempt to take supplies up to the explorers.

Dr Ludwig Becker is buried in an unmarked grave near the centre of Australia and in the centre of the great town of Melbourne, we raised this monument to Burke and Wills instead – making heroes out of failure.

SUSAN CARLAND: In the 19th century, when this monument was built, most Europeans rejected Aboriginal understandings of this land – most, but certainly not everyone – and today this country, following Ludwig Becker’s example, is slowly learning to listen.

BRUCE SCATES: If you’d like to learn more about the issues we’ve raised in this episode, why not catch ‘Susan Carland: In Conversation’. This time Susan’s talking to the anthropologists John Bradley and Sharon Faulkhead in the Monash Centre for Indigenous Studies.

Activities

1. How do the presenters view the Burke and Wills expedition? Do you agree with them?

2. What is Ngurra 1, and how do the presenters contrast Aboriginal mapping of country with European map making?

3. Who was Ludwig Becker? Why do the presenters call him 'a truly Renaissance man'?