Australian Journey Episode 01: Travelling Country interview

The importance of documenting Aboriginal languages with Susan Carland, Shannon Faulkhead and John Bradley.

View transcript

+ -SUSAN CARLAND: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this series may contain images, voices or names of deceased persons.

BRUCE SCATES: Welcome to ‘Susan Carland: In Conversation’. This interview is a supplement to Episode 1 in the Australian Journey series, ‘Travelling Country’.

SUSAN CARLAND: I’m joined today by Dr John Bradley who is the Associate Professor and Deputy Director at the Monash Indigenous Study Centre, and Dr Shannon Faulkhead who is the Senior Research Fellow at the Monash Country Lines Archive.

John has spent most of his life researching traditional communities and ways of knowing the land and in front of us we do have this tangible reminder of traditional ways of knowing the land but I’m going to get back to the canoe later because I want to start by asking you both about a project that you are involved with – the Monash Country Lines Archive, which is all about animating traditional songlines. Can you tell me, what does that mean?

JOHN BRADLEY: We are documenting both stories and songlines. They’re two different things. So if we go back and say ‘why?’: 229 years ago there were 275 languages in this country, there were over 500 dialects. We now have less than a hundred languages being spoken, some of them only one or two speakers. Of that 100 only less than 20 of those languages are strong, that means that all generations are still speaking. Possibly by the year 2050 there will only be two languages left in Australia.

So this project, the animation project, the Monash Country Lines Archive began with the community where I’ve worked for the last 37 years ago watching language die, watching speakers die.

So 37 years ago there were nearly 300 speakers, today there are three old ladies left; and those old ladies were asking questions about, ‘What do we leave behind for our children?’ – like a will – ‘What do we – how do we record? What do we leave behind?’ Paper’s all very well, but paper’s not very attractive and I’d always thought about animation and I – in my own mind, and then I got study leave one year and I storyboarded, I don’t know, 50 or 60 stories. Came to Monash, was brought to Monash from the University of Queensland. Within a week Dr Tom Chandler from IT here at Monash came in and said ‘Is there anything you want animated?’ And I was like ‘absolutely!’

And so that was the beginning and we managed to get some funding from external sources to begin the animation project, took it back to the community and people loved it. So we bit-by-bit build up, built up, until we were given a very big philanthropic gift from the Finkel family which then employed Shannon to work with us.

Shannon as a Koorie woman, had links to Victoria which was fantastic. You know, we knew eventually we would probably have to work into Victoria, but really we’re working Australia wide and Shannon’s job is really holding the nuts and bolts of the whole project together.

SUSAN CARLAND: So Shannon, how has the communities – Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous communities – responded to the project?

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: Well the Koorie communities, there’s been a great lot of interest. They – but our process is that we just let people know what we’re doing and then let people go through their own community processes as to whether they want to be a part of it. So we don’t say, ‘This is going to work for you, this is the best process for you.’ But we make it very clear that there’s a lot of community decisions they need to make before we can animate, so they need to work out one: what story they want animated, then: what language? If they have more than one dialect, what dialect, or what version of the story? Because this is the thing – is that the Monash Country Lines Archive, whilst we recognise the multiplicity of stories, and that they can all coexist, we can only present one story within an animation.

So we we’re constantly having communities contact us but it then, sometimes it can take up to 1, to what, 4–5 years before a community is actually ready to start recording, because the animation is built around the sound recording, so we record the sound, then we do the animation.

JOHN BRADLEY: And there’s a big issue here. If you think of Victoria alone, Victoria was the most quickly colonised part of Australia. Within 10 years colonisation was done. Indigenous communities were rounded up, put into mission stations, killed, you know, the whole tragic story of colonisation.

So when Koorie people in Victoria are wanting to work with us, they’ve actually got to rework a language that has been silent for nearly a hundred years. So it isn’t just a matter of saying, ‘Oh, we’ll just tell a story.’ They’ve got to go back through the archives, they’ve got to work with linguists, they’ve got a band-aid a language back together again and then the huge issue is the difference between a print text (which English is dominated by) and an oral tradition; and you know most communities want to go back to ‘what did our languages sound like, what is the oral tradition’ and that’s a huge ask and, you know, one group of people we’ve worked with in Victoria it took workshops – we had to do workshops to say this is the difference between print tradition reading and an oral tradition.

You know, they did an amazing job but Shannon and I, basically, in some respects, were like social workers, holding traumatised people. And then you realise that trauma is generational. It doesn’t – doesn’t matter how long it goes back – eventually you get to a point where you see that trauma come to again. So we’re not just out there doing animations, we’re holding a lot of other things as well.

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: And it’s not just the trauma. It’s also the fear associated with that trauma because even if there’s communities that have got their languages, like some of the groups that John’s been working with for years, they’re still got speakers but it’s the next generation who are learning it that they’re there’s a fear that they’re not going to do it right or that they’re not going to, they’re going to get something wrong instead of just going, instead of learning it as a child where that fear doesn’t exist, they’re learning as adults.

SUSAN CARLAND: Your work sounds like it’s about doing a lot of bridge building, not just between different cultures or communities but across generations. Is there a particular animation that you can tell us about that illustrates this well?

JOHN BRADLEY: Well, I think all of them, quite frankly. All of them are about this. Like if I can give you an example the cross-generational transfer of knowledge is what we’re buying into basically and is it possible to build a bridge between what the old people think is important or what the historical documents say to bring into living people. So, we’re working with both if you like.

In Victoria we’re working with historical documents, people who want to reclaim and then bring it to life again, further north we go, we’re dealing with last speakers who want to give to the next generation. So, if I give you an example that sort of highlights how it can work is from the community where I’ve worked.

We made a number of animations early on in this program and the children loved them and what you would find is all generations would sit together, they would watch them six or seven times. But every time they watched them the commentary coming from the old people was always different. It was always a different angle or perception about the story, of what was going on, why it was going on and your relationship to that story and this is the way it works for you, but it works differently for you.

And I had an experience of being in a boat and we were travelling out to an island and the grandfather in the boat stopped the boat and he pointed to his grandson and said ‘D’you see that island over there? Tell me the story for it.’ And a little boy who was about I don’t know, six or seven, stood up in the prow of the boat and told the whole story for the island. He’d never been there before. And this is a part of what this project can do. I think there’s a bigger question here worldwide.

Wherever we look where languages are in danger people are trying to reclaim them, so we’re looking at issues of a revitalisation of identity, you know, we want to have something more than the globalised sense of self.

And I think that’s what we’re becoming more and more aware of is that reclamation of a language that has been dormant for a hundred years, trying to save a language where there’s only a few speakers, or working with the language where there are still multiple speakers, at the end of the day it’s about some sense of something bigger than just being – if you like, ‘an Australian’ – it’s about these languages come from this country, nowhere else and each language is tied to country.

So, there are the issues about links, there’s issues about identities, there’s even issues about well-being. You know, we know the research says that people who have their own language and know how to relate to it are going to be in a better position than those that just have the language of the coloniser.

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: And the thing is, is that – I remember when I first started on the program John was saying that it’s not just the language, but the language actually contains knowledge that can’t be expressed in English. It’s through that learning, people aren’t just learning the language, they’re also learning about their country, their people, and their history. So, in a sense it’s their archive that they’re sharing.

And I think that’s possibly where the term has come from for the Monash Country Lines Archive, is that they’re sharing, whilst we’re about language we’re also about that knowledge that there’s continuing within the community.

SUSAN CARLAND: So, is it possible for anyone to see these animations?

JOHN BRADLEY: Yes, you can just type in ‘Monash Country Lines Archive’ and a whole suite of information will come up and the animations will be there as well. When we first started the animation project – especially because it was with the community that I was working with – they were very, they wanted creation stories, dreaming stories.

And then we moved east, to Garrwa language community and we worked with two old ladies who, they wanted to put history down, not the big ‘H’ History of the Academy but their history – we might call it small ‘h’ history.

And there is one very beautiful animation there, that has taken Australia by storm actually, and it’s about a woman herding goats. And we think, so what? And yet it speaks to the role of women during the pastoral industry. The men were off rounding up the cattle, riding their horses. What were the women doing?

The women were servants in the station homes, but also in that part of Australia where this woman came from, goats were incredibly important as a constant source of meat, milk and she had – her mother had composed a song about moving a herd of goats from one place to another – and this old lady sang that song for us and Brent, our animator, animated the goats and this old lady and it’s called ‘Purdiwan’, which means the goats are pretty.

They’re very pretty goats and it’s a very lyrical little story but you could unpack and write a whole thesis about what that’s about.

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: We should also mention that whilst the website is there and we do have a number of animations there each of the animations belong to the community that we work with. So we only put them up once we’ve got permission from the communities.

As we were talking about earlier, it is a journey for the community as well as for the people that are actually doing the animations themselves. So they want to be able to take it back to their community, go through it, make sure that everyone is happy with it before it can go on, go live to public. Whilst there’s a want and a need to share their stories with the wider community, there’s a process involved in doing that. So there could – that process could take a couple of years.

So there are more animations completed than what are on the website but we have to be respectful of that process.

SUSAN CARLAND: And has there ever been communities that have said, ‘We just want to keep this for ourselves?’

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: The Yanguwa did at first, but then they started sharing with family and outside of the community and – which is another story.

JOHN BRADLEY: Actually, there is a breakaway movement here, where I was in the community, taking animations back, putting them on to Mac computers, doing all sorts of things and then I got a phone call from Cairns, I’d got back to my office, and got a phone call from Cairns, and he said,

‘Hey, you Bradley?’

And I said, ‘Yeah’.

‘We want more of them animations.’

I said, ‘Where are you ringing from?’

They said, ‘Cairns’.

I said, ‘How did you get it?’

‘Bluetooth, mate.’ [Laughter]

So you know, let’s not say people aren’t up with technology.

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: And from that the group decided that other people – they realised that other people love the animations as well, and whilst they may not get the same knowledge and information that they do, they wanted to start sharing them and so that’s when they started sharing them.

And so, some of the groups that we’re working with, from day one they say they want them on the website; others they flag that they need to go through some community process beforehand, but generally they do want to share beyond.

SUSAN CARLAND: Thinking about the idea of ‘Country’ now, particularly from the mindset of European colony – colonisers, when they first arrived, they came with this concept of ‘terra nullius’, that essentially the land belonged to no one, and it was there for the taking. Now, the legal idea of ‘terra nullius’ wasn’t repudiated till 1993 with Mabo, which is quite late.

Do you think maybe in the imaginations of white people before then they were starting to feel uneasy about the idea of ‘terra nullius’?

JOHN BRADLEY: I think we’ve actually got to go a step further than ‘terra nullius’ because we still have, alive and well in Australia, ‘mare nullius’. The sea was owned, the sea still is owned by many, many coastal peoples. And I think we’re still fighting ‘vox nullius’, the voices of Indigenous people are still being silenced. So I think there’s three lots of ‘nullius’’, if you like, that we still have to deal with – all embedded within this concept of ‘terra nullius’.

You know I remember that 1992–93, when this happened, and of course we know the press went mad – that it was the worst thing that was going to happen, our backyards are going to be stolen and all the rest of it, and I remember talking to Indigenous people at the time who basically said, ‘Well, so what? We always knew this. This is no surprise.’

And of course the next step to that is native title which is a convoluted legal experience, but I think if we just leave the legal experience aside, it still was a very important thing. But I still don’t think most Australians really understand what it means. You know if we look at what’s taught in the curriculum in any school, even in this University, ‘vox nullius’ is alive and well – the silencing of the voice. You know it gets to the point where some teachers are actually terrified to even bring it up.

And part of that is all Indigenous knowledges are political, just as our knowledges are political. And so how do we deal with a political system that we’ve never really wanted to understand? You know that’s part of the issue here, is that we’re not dealing with something just benign. We’re actually dealing with something that was alive and well and been in this country for 60, 70 thousand years. It just wasn’t cute and exotic, it’s political, it still is political, and then into this mix we throw the history of the explorers.

Well I think the easiest thing to counter that story is that no matter where those explorers went, there was a counter-narrative. There were Indigenous people watching those explorers, doesn’t matter where they were, and they also recorded a story about those explorers. There’s yet to be the book of the Indigenous version of the explorers.

So they weren’t discoverers, there were just re-finders of a country that was well and truly established.

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: I remember when Mabo ruling came down, and it was like the elders, and even down here in Victoria, going ‘Well, of course, we’ve always been here, we have no stories of coming from anywhere else. So how can somebody say that there was no one here when we have always been on this country.’

So it, and they, and John’s right, there are those stories out there that contradict everything that has been reported within the non-Indigenous records of that time.

SUSAN CARLAND: White explorers seem to have enjoyed a kind of mythical status in Australia – even the failures have been celebrated as heroes. Why? What does that tell us about white Australian mentality, and do you think it’s changing over time?

JOHN BRADLEY: Look, I think we have this vision of Australia as a hard place that had to be conquered. You can’t just enter it easily, so it had to be conquered and only strong men were going to conquer it, and therefore if they died, they died valiantly, but quite often foolishly – and I think Burke and Wills is the classic story of foolishness.

You know there were Indigenous people surviving in the country alive, well, happy and yet the arrogance of an imperial mindset said, ‘We will not eat what they are eating, we will not learn from what they are doing, we would rather just curl up and die and be given a hero’s burial’. And I am often perplexed by this and you talk to Indigenous people that I’ve worked with about this and they just don’t get it.

Because it is, if you like, at the end it’s a supreme arrogance, the supreme arrogance that somehow this invention of race in Europe, particularly England, just created a madness of ‘there is nothing these people have to offer, there is absolutely nothing, they are beyond the pale of humanity’ and it’s a huge tragedy and it never ceases to stagger me that we can do this, especially now, and you know, students still get a shock by this – when you say to students in a first-year class, ‘There is no such thing as race, it is a false scientific idea,’ it really shocks students because we still use the word racism which immediately implies that there is such a thing as race, and I’m not sure how far we have to go before we can silence that because, as we know, in more contemporary politics race has risen up again as a determining factor as to why people should be included or excluded. So it’s a long tragic event which we see in our history books and yet, as you rightly said, we celebrate as heroes.

SUSAN CARLAND: So can you tell me something then about the different – the differences between Indigenous ways of knowing country and connecting to the country and non-Indigenous ways of connecting to the country?

JOHN BRADLEY: Look I think the most primary word we have to get around is the ‘relational’ – that everything stands in the relational. The animations speak to this idea of the relational and let’s not get too airy-fairy exotic about this, it’s not just about Dreamtime things, it’s about people being in relationship to each other; people being in relationship to country because that’s where they descended from; people being in relation to human kin and also non-human kin. So I think the word ‘relational’ is a very important one and I think it’s how you learn, but the West also has this knowledge at one level.

I was just thinking about this this morning, Levinus, you know one of our great icons, said that the only way we will ever learn to be human properly is to understand our learning must be through the relational. Now, if we counter that against an institution like a university, we create boxes. One’s called anthropology, one’s called archaeology, one’s called history, one’s called biology, ecology and on and on.

We know these little boxes, and there is still a fear if we choose to actually say, ‘Let’s knock one of the walls down, let’s see what happens when they start speaking to each other.’

Now here, at MISC, we have to be multidisciplinary because we know when we work with Indigenous knowledge that any of these so-called ‘ways of knowing’ are going to enter, percolate, become something else, and we have to learn to understand how.

SUSAN CARLAND: Do you have anything to add on the differences or similarities?

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: Well, from Indigenous perspective, we’ve always said that we can’t separate these areas out, they, they all coexist in one story.

So to actually try and say, ‘Oh, this is – belongs to this area of study or this belongs to this area of study – it’s not possible because it is a – it’s almost like – well it is – a lived experience. And so it’s holistic. You don’t, sort of, divide it up. Even like families or groups – their connection and their part in life. It’s not like – people talk about hierarchies, you don’t – when you actually live in that situation those hierarchies aren’t hierarchies. It’s sort of almost like a safety mechanism.

So I don’t know whether it is a European or non-Indigenous perspective, or whether it is a difference between groups, or whether it is a difference between lived and an academic approach to how people live.

SUSAN CARLAND: So does a term like ‘ownership’ really do justice to the way Indigenous people connect to the country?

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: I don’t, no, is the simple answer, because I don’t think that’s a term that really exists. Like before ‘terra nullius’ and native title it was – it was always – the terms were always, ‘We belong to the country.’ It’s not saying that – it possibly is a form of ownership – I’m not sure, but it was never in the sense that the land owed us something. It was sort of like we owed the land.

JOHN BRADLEY: And I think, I’m just thinking about this question now, you know, as a speaker of an Indigenous language, there was no word in one of the languages I speak for ‘own.’ It just, it’s not even a word for it. If you lay claim to something, people will then say, ‘How – on what basis do you lay claim to this land, to this sea, to this boat?’

It demands then the experience of the relational to be able to say, ‘I lay claim because of these factors.’ So this term ‘ownership’ is far too simplistic and it gets us into lots of trouble.

And I think, yeah, just thinking then, there is no word for owned. It’s about an explanation of how you come to be, to say that this thing may have some relationship to you.

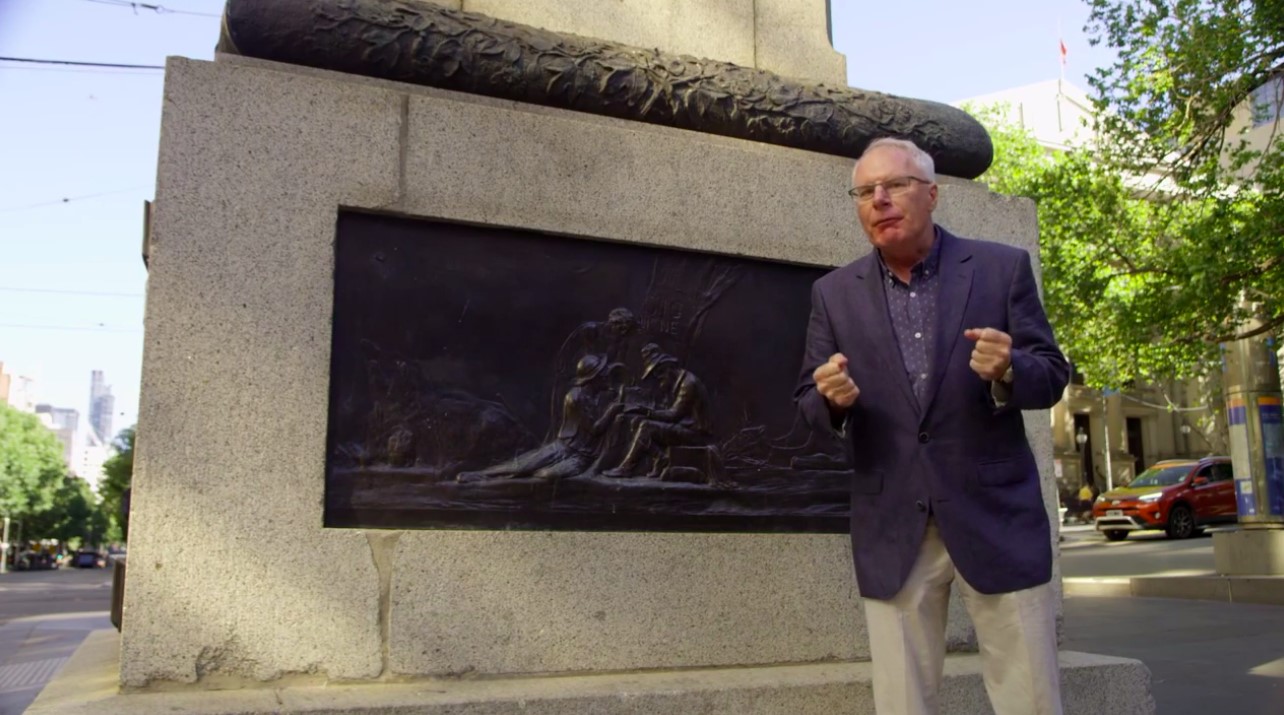

SUSAN CARLAND: So then tell me about this canoe.

JOHN BRADLEY: It’s two big stories. This canoe was gifted to me in 1981 in Borroloola where I was working. My appendix burst. I nearly died. I was flown out, when I got back an old man by the name of Pirodideono had made it for me as a gift.

But I think more importantly, this craft tells us a huge story of an unknown part of Australia and that is what we generally call the Macassans, the group of south-east Asian voyagers who came to Australia for at least six centuries to gather trepang (bêche-de-mer), to gather sea turtle shell, to gather eucalyptus hardwoods, to gather trochus shell, who worked in relationship with Indigenous peoples across the north coast of Australia as – well, they were basically the labour force, to gather trepang, to work with people.

Then, at the end of the season, the boats were filled and the dugout canoes were left behind as part of a payment. So it’s symbolic of an amazingly rich part of Australia’s history. You know if we look at that part of a history, what else happened?

We had intermarriage between south-east Asia and Australia long before white people even knew Australia existed, we had contact with the Islamic world long before Australia was settled by white people. And that Islamic culture is still visible in parts of cultures in north-east Arnhem land, where there are hymns that are now so thoroughly Indigenised but are actually prayers to Allah for safe journey.

They don’t carry that same meaning now, but we know that when the linguists work with it, that’s what they actually are. There was intermarriage. There are still families in Australia who know their families back in south-east Asia and vice versa.

You know this boat reminds us that the first international relations in the history of Australia was between Indigenous people and people from south-east Asia; the first trade routes were between Indon– were between south-east Asia and Australia; the first product was not merino sheep to be exported, the wool, it was trepang, that made its way to the Imperial courts of Nanjing and Beijing in China.

It’s an amazing story and yet one of the most unknown stories, I think, at a primary school level, a high school level and even in a university like this.

SUSAN CARLAND: So, obviously this boat’s been on quite a journey. What is – what’s next in your journey, where are you off to after this?

JOHN BRADLEY: Well, my journey at the moment is very much, after 37 years, trying to find out ways to give stuff back to a community in a way that they can use it. If we look at any community in Australia – any community, Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland – if a language dies it takes about four generations for a community then to say, ‘What did our old people have? What did they have that might be useful to us?’

Now, where the documentation is strong, where it is detailed, where it is complex, Indigenous communities have a lot to work with. Unfortunately, say in places like Victoria, it wasn’t always well documented. So people really have to just hang on to the most precious little bits of information they’ve got.

So really my job at the moment is trying to find ways to give back to a community that has given to me, so that in four generations’ time they will have a body of knowledge that they can do something with.

At the moment I’m caretaker for all of this, one day it will go home, but while it’s here at the University we have students working with these objects to do their honours thesis in the Monash Country Lines Archive, we have students who have done their honours and masters theses so it’s got an immensely academic important role as well.

SUSAN CARLAND: Shannon, what’s next for you?

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: Short term, continuing the Monash Country Lines Archive but also taking it into new spaces. As John was describing what he was hoping to take back to his communities. We have also been in discussion about ways that the animation can be more interactive so allowing people to actually walk-through country and taking it, not just really to the next stage.

JOHN BRADLEY: The art events.

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: But, but yeah – oh, the art events! [Laughter] Yeah, so as the technology develops we have more and more options as to what we can or can’t do in terms of bringing new ideas to communities in how that they can preserve language and knowledge in that 3D form. We also are doing an exhibition this year.

One of the young Taungurung, one of the groups that have worked on the Taungurung animations, is curating in an exhibition on the cosmos, so because the animations they’ve worked on have all been about astronomy and cosmic – cosmos she felt that that’s what she was connected to, so yeah.

SUSAN CARLAND: So a lot’s coming up

SHANNON FAULKHEAD: Yeah.

SUSAN CARLAND: Lots. 70,000 years of things have happened and a lot more is coming. Thank you both so much for your time, I really appreciate it.

JOHN BRADLEY AND SHANNON FAULKHEAD: Thank you.

Activities

1. What are John Bradley and Shannon Faulkhead engaged with?

2. How do Bradley and Faulkhead view the Burke and Wills story?

3. What unknown stories do Bradley and Faulkhead believe are important to know?