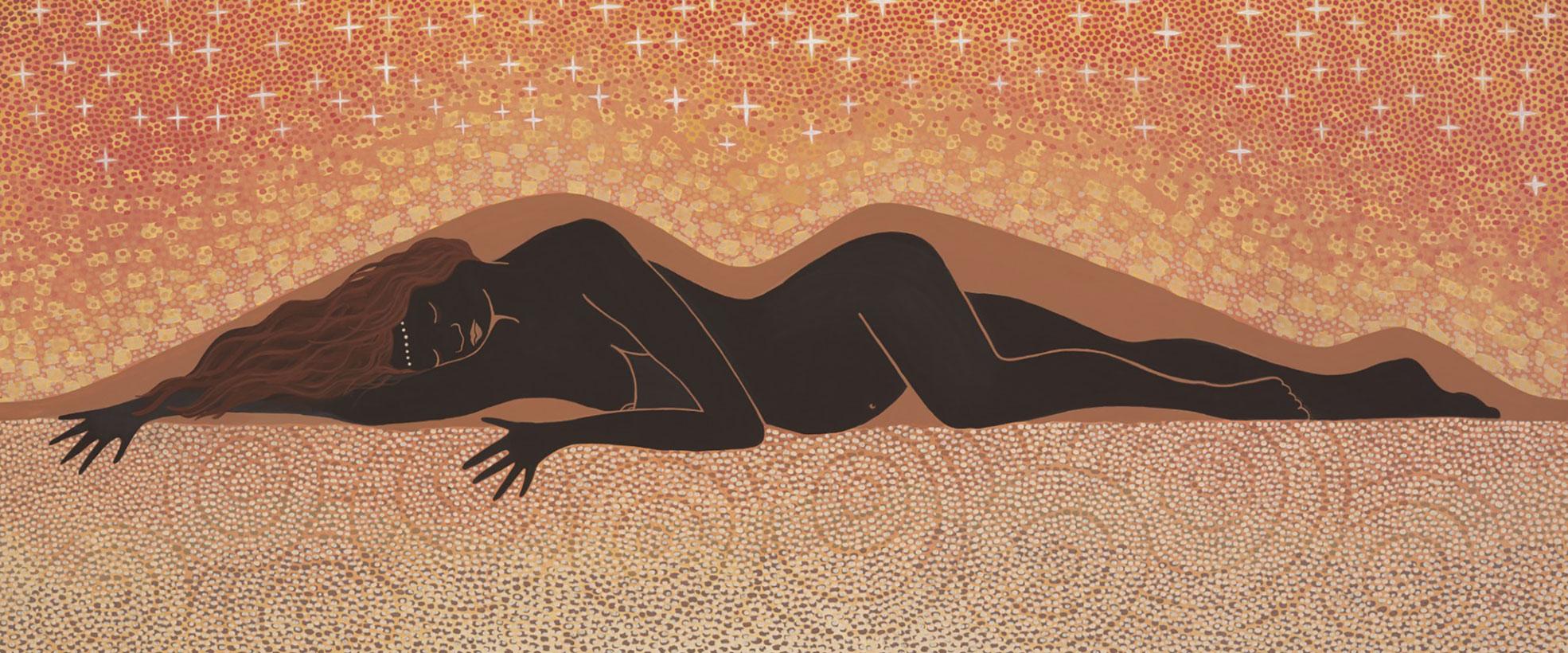

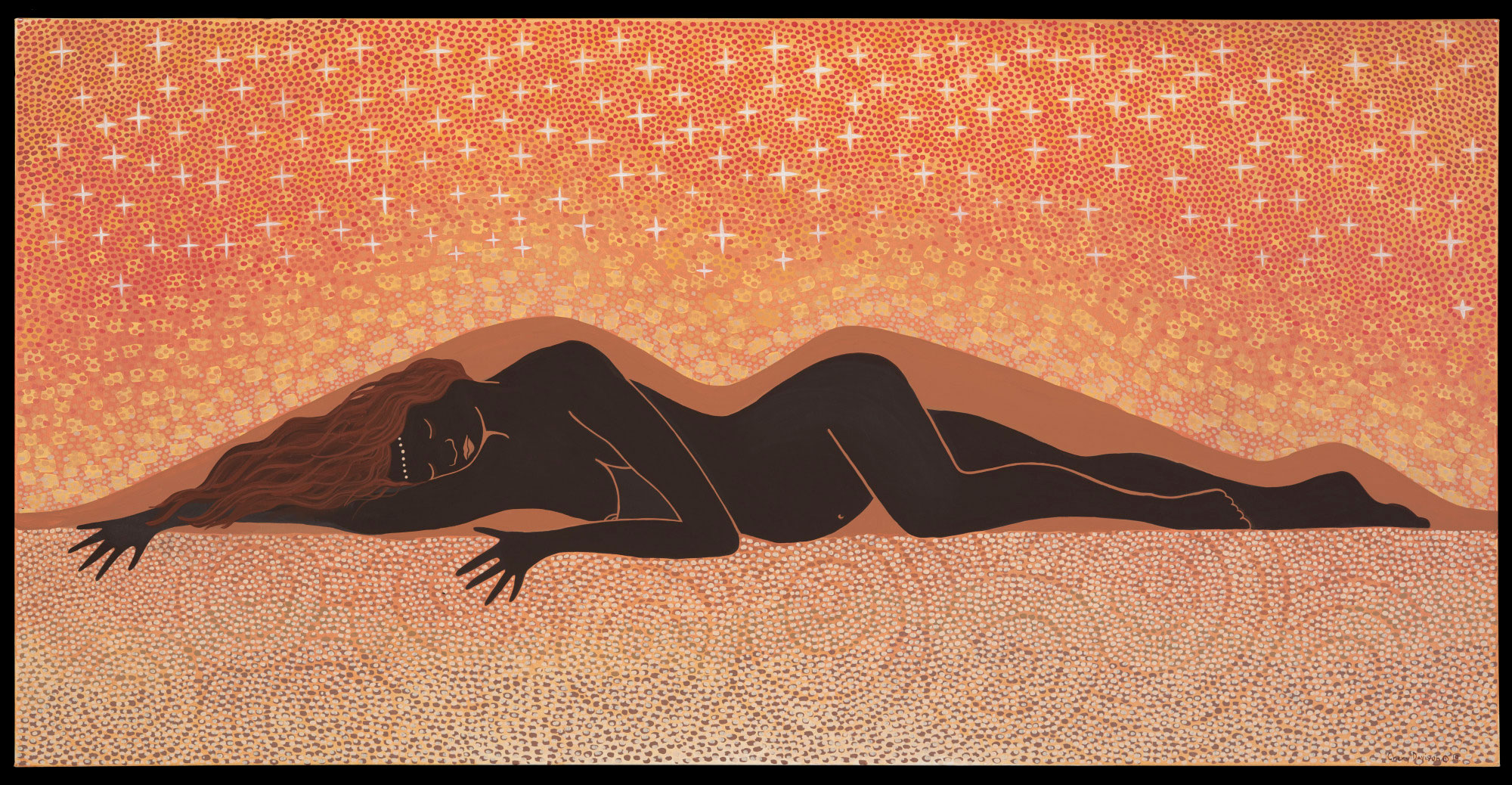

Gulaga — Mount Dromedary

The Gulaga story

Cheryl Davison, Walbunja/Ngarigo:

One day Gulaga and her two sons, Baranguba and Najanuga, were collecting bush tucker. When Baranguba asked if he could go fishing, Gulaga said, ‘No, you’re too young, you’re to stay next to me’.

As they walked along, Baranguba insisted that he go fishing. But Gulaga said, ‘No, no, you have to stay next to me, it’s not safe to go fishing by yourself’. But Baranguba snuck away. He made himself a canoe and he rowed out to sea, where a big wave came and washed him off the canoe ... He laid down in the water — and that’s where he still lives today.

When Najanuga, the younger son, saw this, he wanted to move away and set up his own camp. But Gulaga said, ‘No, you’re too young, you just sit here right next to me’.

So now she lies there, looking out at the sea at her older son, with her younger son right next to her, in arm’s reach.

Video: Mount Gulaga and gurung-gubba

+ -Djiringanj Yuin knowledge-holder Warren Foster explains the sacred significance of Mount Gulaga and shares his ancestors’ view from the shore when James Cook sailed past his country. Produced by the ABC in partnership with the National Museum of Australia.

Transcript for Mount Gulaga and gurung-gubba video

Warren Foster

WARREN FOSTER: Captain Cook, when he sailed up the coast, he’s got his diary and he writ down all his stories about his travels, yeah. And where he’d been, and we also have our stories but it’s not written down. We seen him when he sailed in the Endeavour, yeah, and the old people remembered him and they handed stories down. We were taken to them places and shown them stories.

Where we are, we’re in Djiringani Yuin country and we go two sacred mountains. Gulaga – she holds a lot of creation stories and Biamanga, where our laws and ceremonies come from. And being where we are, with our two mountains, we had to allow other different mobs to come down, come through country and go and do ceremonies. There was the big bunaans, corroborees, and there would have been abundance of food, people.

When Captain Cook, James Cook, sailed up the coast there, we watched him and when our old people seen him they was wondering, what is that? Minjajin (look there). What’s that? ’Cos we didn’t see something so big and white swimming on water.

And the only big thing we see swimming on the water is birds, budjans. And he was shaped sort of like gurung-gubba, the pelican. So our old people thought he might have been one of them big budjans coming back, back from Dreamtime. Because when we talk about Dreamtime we talk about it as one time. And when we do ceremonies we go back into that one time.

And all the old people they all started lighting fires, putting the smoke signals up, to look out here, minjajin. Yanaga (walk) minjajin. To look out in the gadhu (ocean). What’s that? Big pelican. Now with the story of the pelican, gurung -gubba, he’s a real greedy fella. So when you’re fishing, he’ll come and steal your fish. And he’ll keep on taking your fish. So you had to watch him. So just the same as us watching him when we’re fishing, we had to keep an eye out on that boat. Because if he’s a big pelican we don’t know what he’s going to do, yeah. He might take off that water, come in and scoop, scoop all us up, all the people. Little did we know that eventually this big bird would sail in and he did eventually scoop up everything and steal everything off us.

Cook sailed past and he named our sacred Mother Mountain, Mount Dromedary. And dromedary is a camel. All our mob, no matter where we are, we look at the mountain and we always see a woman laying down. Even when you’re out on the ocean there, you see a woman. The real name for the mountain is Gulaga. Gulaga means Mother Mountain. She gave birth to all the Yuin people. Gulaga to us is as sacred as Uluru is to them Mutitjulu mob out there in the desert. If there was no mountain, Gulaga, there wouldn’t be any Yuin people. Not only the Yuin people, but human beings. That’s where we come from and when we take our journey, that’s where we’ll be going. For a man to be sailing up the coast and look at our Mother Mountain and call her a camel is the biggest insult for a lot of our people anyway, or for me anyway.

How would I describe my connection to land? I’m like this tree. I’m rooted down in the ground. Done ceremony for the land. I am the land. I’m not part of it, I am it.

That pelican, he did eventually come in and scoop up everything and take the lands, steal all the children. Put his name on the mountain. One thing he couldn’t take away from us was that connectedness that we have to our Mother Mountain, Gulaga. That goes for all the Yuin people up and down the coast.

Mount Dromedary

+ -

Gulaga has always been a sacred mountain for the Yuin people of southern New South Wales. Unaware of this, Cook renamed the distinctive hump-shaped landform ‘Mount Dromedary’ as he sailed up the coast.

Wallaga Lake Reserve

+ -

European squatters and timber cutters came to the area around Gulaga from the 1830s, pushing Yuin people off their land. In 1891 colonial authorities established the first Aboriginal reserve in New South Wales at Wallaga Lake, in the shadow of Gulaga.

Many Yuin people with links to Gulaga were forced to live there, under the eye of a non-Aboriginal manager. For people from here, the stories of these times are part of the Cook story.

Audio: Life on the reserve

+ -Life on the reserve

Yuin Kelly (Yuin), Lorraine Naylor (Yuin) and Eric Naylor (Kamilaroi) reflect on growing up on the Wallaga Lake Reserve on the south coast of New South Wales.

Transcript for life on the reserve audio

Yuin Kelly, Lorraine Naylor, Eric Naylor

HOST: Yuin Kelly talks about life on the [Wallaga Lake Aboriginal] reserve.

YUIN KELLY: The manager’s wife used to come around and check all the houses and see if they were all clean and, the biggest scariest part was the welfare though, eh, ’cos that meant something more serious and yeah.

Mum was smart like, all the other women and mums back in the days on protecting us. Though we were under the Protection Board, our mums were the true protectors, our dads, our uncles, our aunties, grandparents. Mum would always think ahead of the welfare.

And I remember, a welfare woman coming, some days and, ‘Where’s your daughter?’ Mum would have me hiding in the food cupboard behind the Pick-Me-Up sauce and the bit of flour and white sugar and all that.

Other times when the welfare would come in, this is on Wallaga, Mum would say, ’Run down the track there. There’s a big log down there, a big tree down there. Go down there and hide ‘til the welfare’s gone and I’ll come and get you’. And I’d run down and there’d be other children there hiding too.

HOST: Lorraine Naylor talks about life on the reserve.

LORRAINE NAYLOR: You know as a child growing up here under the white manager, to me it was best days, you know? Because we learnt and we learnt respect and discipline. Things were different but really hard, you know, for our Mum to feed all those kids. We had to go to school every day. If we missed one day, welfare man would come all the way from Bega and pick us up and take us to school even if it was lunchtime, so.

In the early time when I was really small, because Wallaga Lake had its own little school, and we went to school here up until we got to Sixth Class and then we went to Bermagui Public, ’cos we got a bit too big.

Because the teacher from, at Wallaga Lake, was the manager’s wife and she didn’t know anything. She wasn’t a qualified teacher, so, all we used to learn, you know, just learn a few maths with blocks and play with blocks and make handkerchiefs and make aprons.

HOST: Eric Naylor talks about life on the reserve.

ERIC NAYLOR: When I grew up here it was fun, always had something to do. I really followed all the old people round. I learnt a lot off them. Fishing every day, we used to go rabbiting ... just about every day ... or I would approach spearing fish. We had that much to do, you know, we were never bored. And yeah, it was good growing up here in Wallaga.

You know years ago you used to be able to walk into a house, any house on Wallaga, help yourself to a cup of tea and a bit of damper ’cos that’s the way it was. And the old people was very, very strict and you had to be inside before dark. If you weren’t they come looking for you.

Education resources

These resources cater for students in Foundation to 6 and all activities align with the Australian Curriculum.

Curriculum topic: Indigenous Australia, Environment, Australia as a nation

Year level: Foundation to Year 6

Foundation

+ -Year 1

+ -Year 2

+ -Year 3

+ -Year 4

+ -Year 5

+ -Year 6

+ -Just like the story of Gulaga, there are many landforms within Australia that hold meanings and cultural stories that originate from First Nations people. The original custodians from a region are the only people able to retell and create artworks relaying the stories attached to that landmark. This is called a national cultural protocol and is a practice that all First Nations people abide by.

A family story that has been passed down for many generations belongs to a family group that were born from that land and have a blood connection to it. The Museum abides by these cultural protocols and all stories shared have been in collaboration with knowledge holders.

Activity

+ -Research a landform from anywhere in the world that holds cultural significance and deliver your findings to your class.

Points to mention:

1. Who or what group of people have a connection to this landmark?

2. Are there stories attached to this landmark that are available in written form?

- If yes, what are they and do they hold sacred lore, considerations and permissions?

- If no, why do you think you cannot find a written documentation; is it possible there is only oral history?

- Collect the story when delivering to your peers.

3. Are there artworks created about this landmark?

- What are the artwork descriptions?

- Who created the artworks?

4. Does the landform have a resemblance to an object, human or animal?

- Collect an image to talk to when delivering to your peers.