Learning module:

Movement of peoples Defining Moments, 1750–1901

Investigation 2: Migration case study

2.1 Japanese at Broome

What happened to people who came to Australia during the nineteenth century?

Here is one case study about Japanese migrants who came to Broome in northern Western Australia. This can be used to help you develop further knowledge, understanding and empathy for people who migrated at this time.

Your task is to read the evidence and complete the task that follows. The task will ask you to assess 12 statements about the experiences of this group.

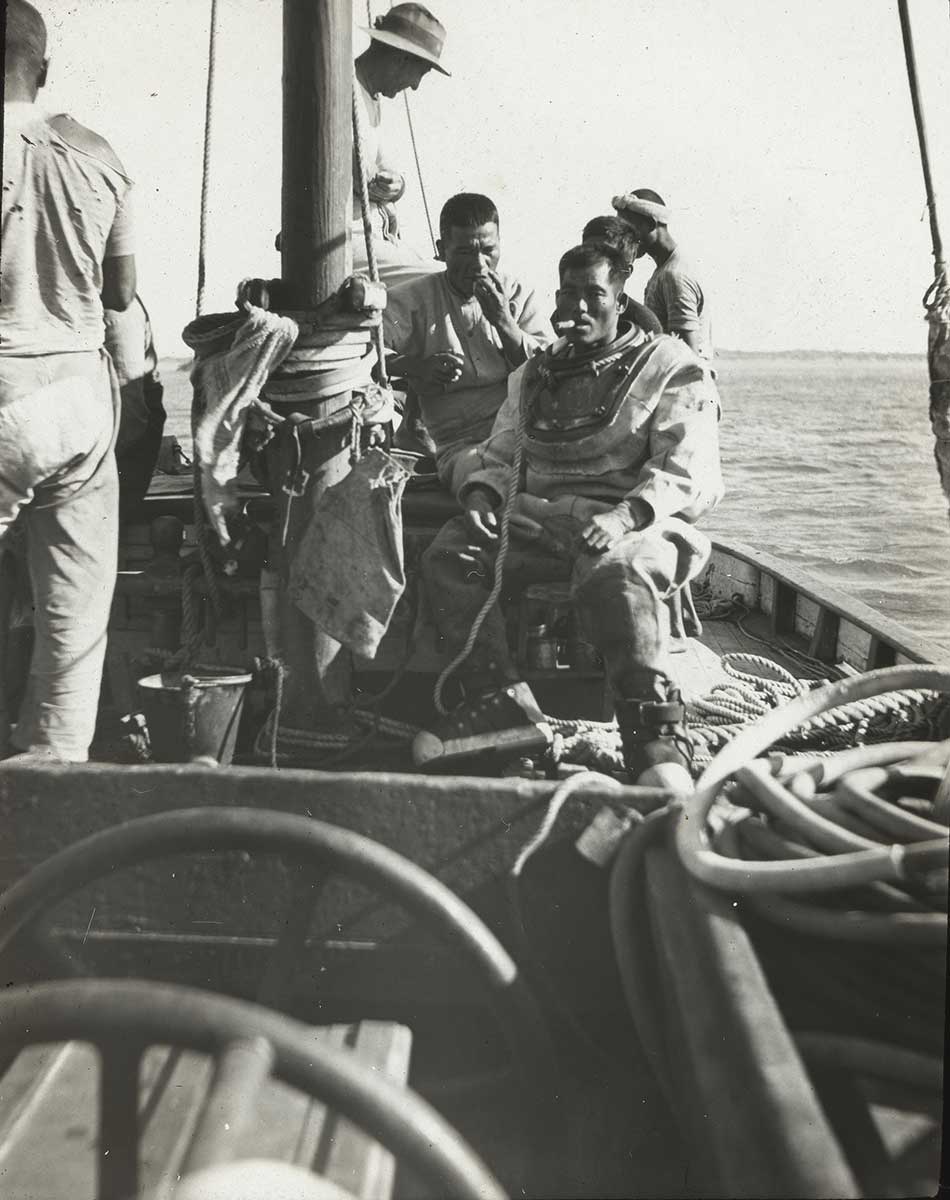

Evidence File A

South Sea pearls

Pearlshell had been harvested and prized by Aboriginal people long before European contact, and was traded inland from the coast. Since the mid-1800s riji (carved pearlshell) was exchanged extensively between Aboriginal communities across northwest and central Australia. These carved iridescent shells continue to be valued for their associations with water, rain and life.

The pearl oyster Pinctada albina was first collected by entrepreneurs at Shark Bay in 1850, but it was the 1861 discovery of the far larger Pinctada maxima shells at Nickol Bay that had prospective pearlers flocking to Western Australia.

In the 1880s pearlers turned their sights to Roebuck Bay (Broome) in the West Kimberley. By 1910 Broome was the largest pearling centre in the world, benefitting from newly introduced diving suits, fertile waters and a booming international pearl button market. Among the major players were the steadily rising Japanese and Chinese pearlers.

Western Australian Museum, Pearling timeline, http://museum.wa.gov.au/explore/lustre-online-text-panels/pearling-time…, viewed 10 September 2020

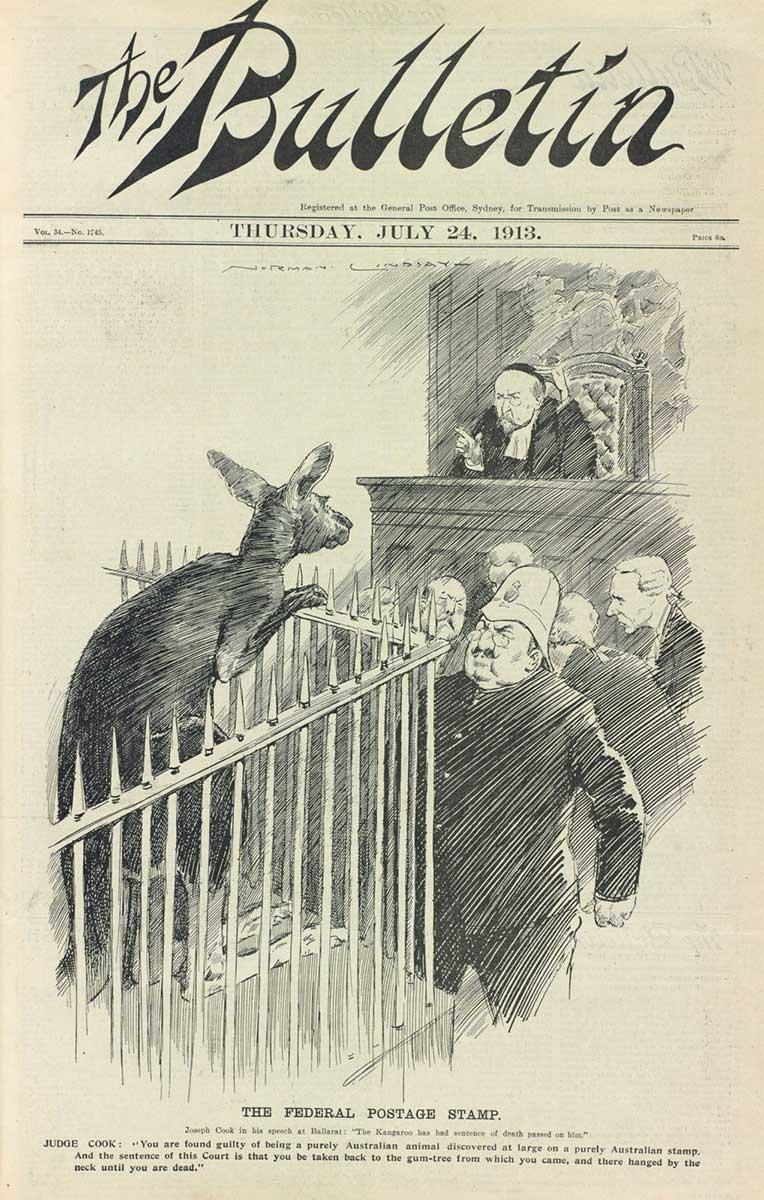

Evidence File B

Japanese pearl diver and lugger crew, Broome, 1911

Evidence File C

Working conditions

As Aboriginal divers would not use the diving suits, pearlers began to indenture Asian workers from as early as the 1870s. They were exempt from the 1901 White Australia legislation, and this practice continued until the 1960s. Over the last century, thousands came to work in pearling via Singapore from Malaysia, China, Japan, Philippines, Timor and Sri Lanka, on three- to five-year contracts. Conditions were harsh. Long weeks were spent at sea in cramped, unsavoury conditions as the shell dried on the decks of the luggers and cockroaches infested the cabins. No refrigeration meant a diet of fish and rice, and with no radio communication to advise on approaching cyclones many boats were lost at sea. Divers worked the seabed from sun-up to sundown, dependent on the commitment of their tenders and engineers who operated the lifeline of air from small platforms. Low pay, restricted rights and limited tenure meant divers could be sent home at any time, especially if they transgressed the racial laws preventing ‘cohabitation’ with the ‘natives’.

Sarah Yu, Bart Pigram & Maya Shioji, ‘Lustre’, Griffith Review 47, https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/reflections-pearling/, viewed 6 October 2020

Evidence File D

White Australia policy

Official alarm at the dominance of the Japanese divers led the Commonwealth government to decide … that from January 1913 white divers would replace the Asian workforce. … [11] British Navy-trained men … arrived in Fremantle in January 1912. … But the experiment had tragic consequences. The English divers failed. They were too expensive, they were not as successful as their Japanese rivals and their skills developed in engineering projects in Europe had little relevance for pearl diving. Three of the divers died of the bends, the others left Broome in disgust.

Henry Reynolds, North of Capricorn, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2003, p. 135–6

Evidence File E

Indentured labour

The … contracts [with Japanese divers] appear to have been very sketchy and unsatisfactory documents. They were capable of the interpretation that the wages were due only at the completion of the period specified in the Articles, that is at the end of three years (this, in fact, was the custom in the sea-faring world). Some of the employers attempted to adhere to this interpretation. The contracts contained no provisions dealing with sickness or medical treatment. Some employers seem to have taken advantage of this to charge for medicines and, where a Japanese was repatriated for medical reasons, to deduct from his wages the entire cost of the journey to and from Australia.

DCS Sissons, ‘The Japanese in the Australian Pearling Industry’, in Bridging Australia and Japan: Volume 1, edited by Arthur Stockwin and Keiko Tamura, Canberra, ANU Press, p. 11, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1q1crmh.8, viewed 6 October 2020

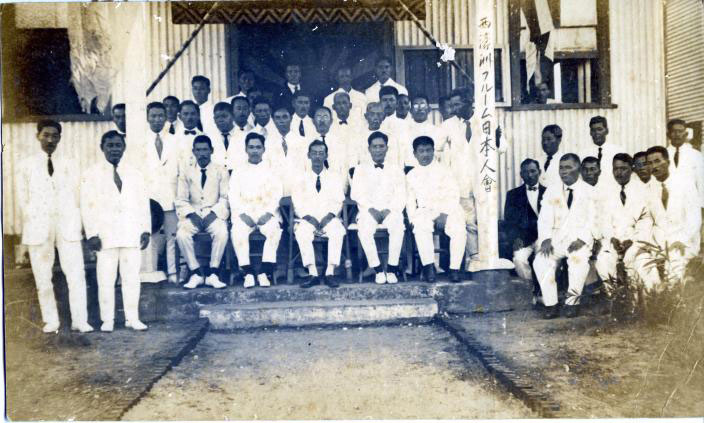

Evidence File F

Members of the Japanese Club, Broome

Evidence File G

Dangers of pearling

Prior to World War I, up to a third of indentured divers lost their lives through disease, diver’s paralysis or drowning during natural disasters such as cyclones … The more shell a diver collected the more money they made, increasing their job security with the pearling masters, so the more risks they took … Many divers now lie in unmarked, ‘lonely’ graves that dot the Kimberley coast, and in every pearling port local cemeteries have separate sections for Chinese, Japanese, Malay and the other groups. Today, local communities such as the Chinese and Japanese in Broome continue to honour those who died with annual ceremonies such as Hung Seng and Obon.

Sarah Yu & Bart Pigram & Maya Shioji, ‘Lustre’, Griffith Review 47, https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/reflections-pearling/, viewed 6 October 2020

Evidence File H

A multi-racial workforce

By 1900, Broome was the centre of the pearling industry, employing more than 2000 men, 1700 of these being either Japanese or Malays, while men from the Philippines, China, Timor and the Macassar Islands, and Aboriginal men made up the remainder. The 1901 census recorded a fleet of 149 hard-hat diving vessels and four skin diving vessels. The skin diving vessels employed 36 Aboriginal men, while the rest of the pearling workforce was made up of 55 whites, nine Chinese, 210 Japanese, 448 Malays, 230 Manila men and 46 others of unspecified nationality.

Heritage Council of Western Australia, Register of heritage places — assessment documentation, Broome Cemetery, http://inherit.stateheritage.wa.gov.au/Admin/api/file/c740f2b9-0bca-a65…, viewed 6 October 2020

Evidence File I

A variety of workers

The white [ship captains] … — the pearling masters as they were known — lived in a manner [like] that of white expatriates in the tropical colonies of the British empire … They had … servants in their verandahed houses and large gardens … — Aboriginal boys and girls for rough, unskilled work, Chinese gardeners, Malay housekeepers, Japanese cooks … The pearling masters dressed in white cotton suits, white shoes and pith helmets maintained by their own servants. When they relaxed they dressed in batik sarongs.

In 1901 the Asian workforce came from three sources — about half were Malays, the rest were Filipinos and Japanese. The Japanese were gradually becoming the most prominent component of the immigrant workforce … Skilled and experienced divers could command high wages [and] a share of profits.

Like many towns right across North Australia, the small northwestern communities were host to Japanese brothels … the general view was that they were well-run and orderly establishments … [Japanese] shopkeepers were [considered] courteous and obliging.

Henry Reynolds, North of Capricorn, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2003, p. 124–7, 132–5

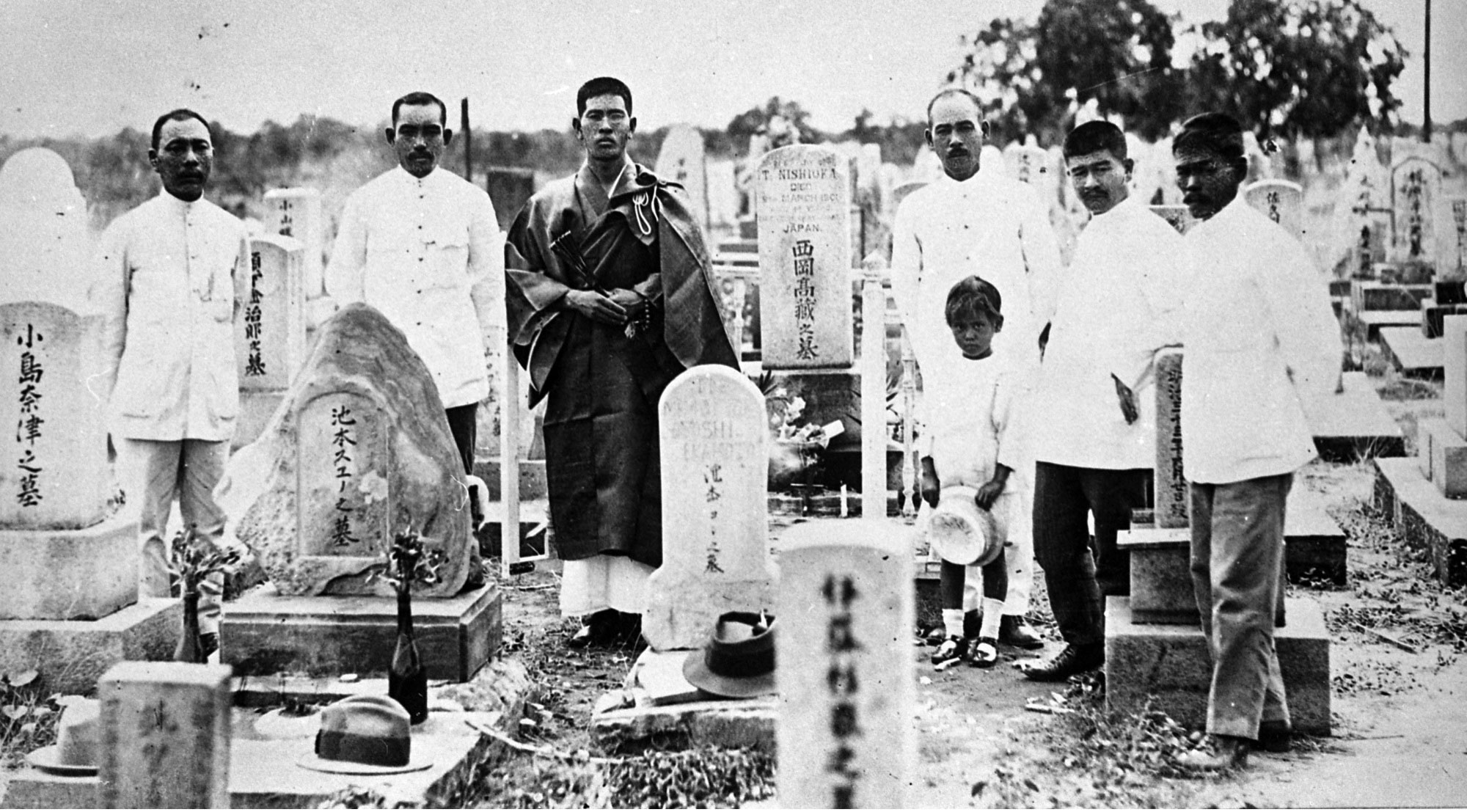

Evidence File J

Photograph of Japanese residents at Broome cemetery

Evidence File K

Japanese cemetery at Broome

The Japanese cemetery is the resting place of 919 Japanese divers who lost their lives working in the industry. The first recorded burial in the cemetery dates back to 1896.

Many of the Japanese men buried here were born in a place called Wakayama in the south-east corner of Honshu, Japan’s main island. People from this region have historically followed the God of the Sea called Namikiri-Fudo and are famous for their abilities as fisherman and divers.

A plaque at the entrance says in part, During their years of employment in the industry a great many men lost their lives due to drowning or the diver's paralysis. A large stone obelisk bears testimony to those … lost in the 1908 cyclone. … In the year 1914 the diver's paralysis claimed the lives of 33 men.”

There are 707 graves (919 people) with most of them having headstones of coloured beach rocks.

Most of the Japanese tombstones have bottles embedded in their foundations. These are part of the yearly Shinto festival called ‘Obon.’ On August 15th, the Japanese pay their respects to the dead by cleaning the grave sites and leaving offerings of food, flowers and saki to the spirits.

Heritage Council of Western Australia, Register of heritage places — assessment documentation, Broome Cemetery, http://inherit.stateheritage.wa.gov.au/Admin/api/file/c740f2b9-0bca-a65…, viewed 6 October 2020; Find a grave, Japanese Cemetery, https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2458068/japanese-cemetery, viewed 6 October 2020 and Monument Australia, Japanese Pearlers https://monumentaustralia.org.au/display/60167-japanese-pearlers, viewed 6 October 2020

1. Now examine 12 statements that will help you to review the experiences of Japanese pearl divers in Broome in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Your task is to assess each statement by choosing one of the five possible answers for each one.

2. Does this summary of Japanese migrants in Broome in the late nineteenth century support the evidence you have examined in this case study? Explain your answer.

Exploring further

As an extension to this activity, research an individual who was a Japanese migrant and see what happened to him or her.