Learning module:

Migration experiences Defining Moments, 1945–present

Setting the scene: Migration and Australia

3. Australian immigration before 1945: Background information

- 1788

- Free and assisted migrants

- Impact of gold rushes

- Restrictions on non-Europeans

- Federation and White Australia

- First World War

- Second World War

1788

The arrival of the First Fleet in 1788 was the start of the European colonisation of Australia, and the start of a process of mass immigration.

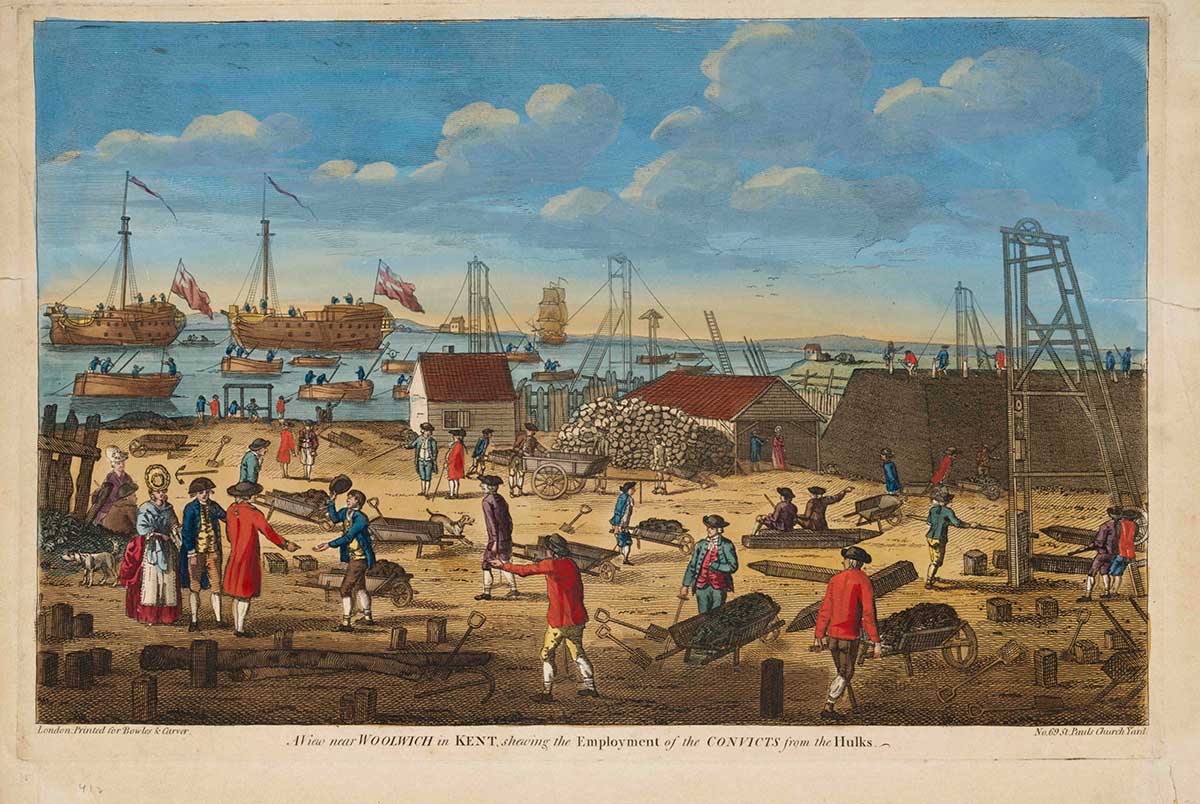

The first migrants were mostly unwilling — 778 convicts. Over the next 80 years about 160,000 convicts were sent to Australia, mainly to New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). Convict transportation ended in 1840 in New South Wales, in 1853 in Tasmania, and in 1868 in Western Australia. Most convicts stayed in Australia after the end of their sentence.

The First Fleet also included officials and soldiers. A few stayed on in New South Wales, becoming the first of an increasing number of free settlers.

Free and assisted migrants

From the 1820s large numbers of free settlers started to arrive from Britain. As colonies expanded, there was a demand for more free settlers who would work as labourers.

During the 1830s and 1840s colonial governments and some private organisations started subsidising the costs of poor migrants to move and settle in Australia. Many of these migrants were families and single women. Colonial governments wanted to dilute the convict and ex-convict social influence, and to increase the number of agricultural and domestic workers and the number of women migrating to Australia.

Nearly all the convicts and the free and assisted migrants were British.

Impact of gold rushes

The discovery of gold in 1851 brought large numbers of single men from British and other European countries, especially Germany. It also brought large numbers of Chinese people to Australia, their travel having been organised by businessmen based in their home areas in China. The Chinese were in effect work teams bound to work for their organiser who was repaid from the earnings of the team. The Chinese migrants were expected to return to China, as most were using the rushes to create wealth for the families they had left behind.

Many of the British and other European migrants stayed after the gold rush, and brought out young families. Large numbers of Chinese also stayed, but tended to be isolated into ethnic settlements within the major cities.

Restrictions on non-Europeans

The large numbers of Chinese migrants in the 1850s, and then again in the 1880s when they were brought in an organised system to work in cities, led to government restrictions on the number of Chinese passengers that a ship could bring to Australia. There were also social restrictions, created both by the settlement of Chinese into distinct ethnic areas, and also by the refusal of other residents to treat Chinese people as regular settlers.

Federation and White Australia

By 1901 at Federation, the colonies were happy to see their individual restrictions formalised into a common immigration restriction law, a White Australia policy. This included the passing of a law to stop the immigration of, and to deport, the South Sea Islanders who had been brought to Queensland as labourers in the sugar cane plantations. There were still non-European groups in Australia under the White Australia policy: Aboriginal people, Chinese people in major cities, individual Chinese market-gardeners and traders in rural areas, Japanese pearl-shell divers in northern Australia, Afghan traders in remote areas, and those South Sea Islanders who were able to establish that it would be unfair to deport them back to their original island homes. These groups were discriminated against in various ways, such as being ineligible to vote or to receive the same social service benefits of other Australians. If they were considered citizens at all, they were second-class citizens.

You can find out more about this in Investigation 4.

First World War

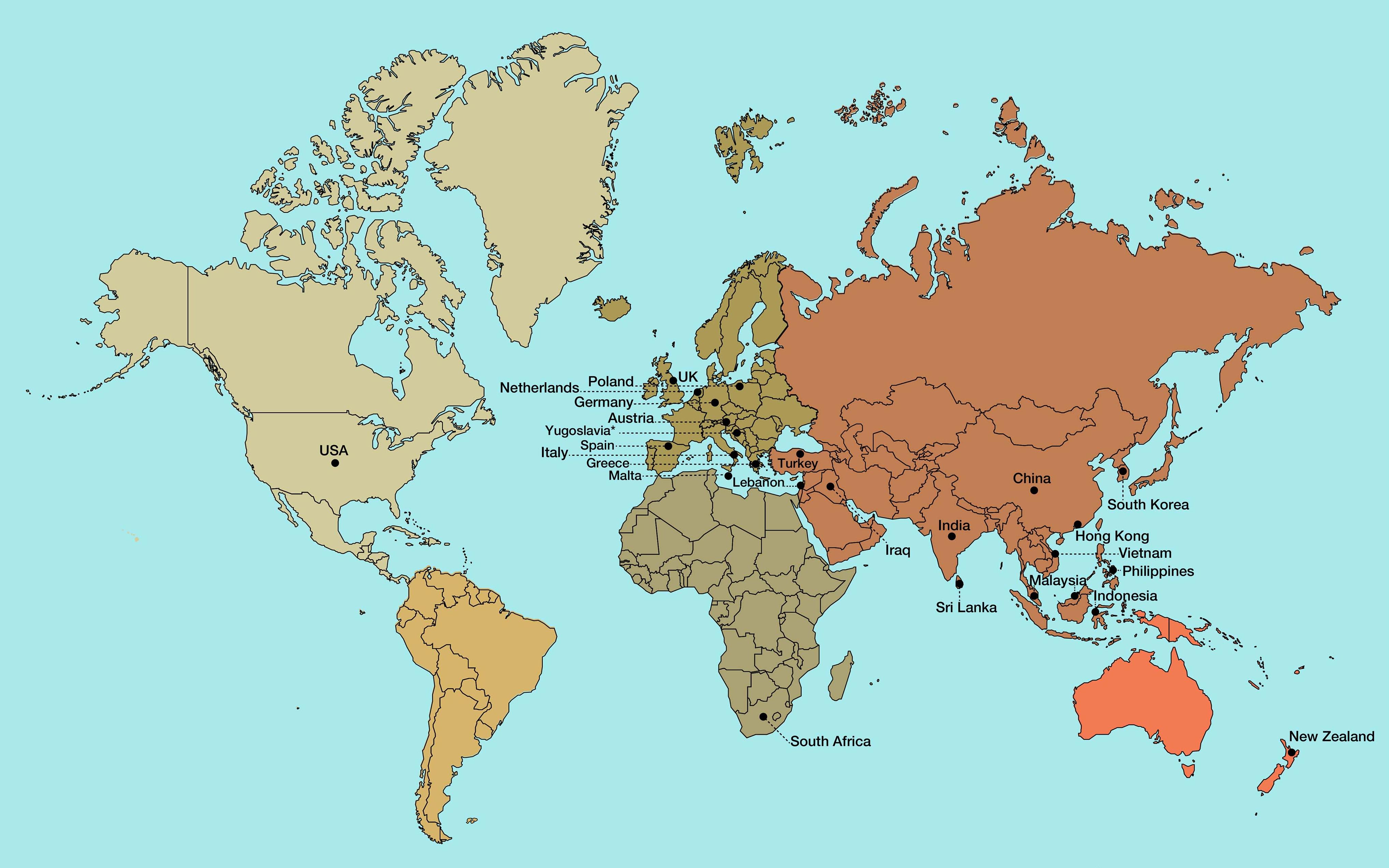

The Federation period had seen a continuation of efforts to encourage predominantly British migration. By 1911, of the 22 per cent of the population that were migrants, 78 per cent were from England, Ireland or Scotland. Four per cent were from Germany, four per cent from New Zealand, nearly three per cent from China, and less than one per cent from each of the remainder of the ‘top ten’ sources of migration to Australia: Italy, India, USA, Denmark, Sweden and Norway.

Second World War

The First World War, and then the Great Depression of the early 1930s, stopped nearly all migration to Australia. Then came the Second World War, and when the Japanese advanced through south-east Asia and much of the Pacific, Australians believed that their small population made them vulnerable to attacks from more populous Asian neighbours. In the postwar world, defence and population development were seen as reasons for increasing the intake of migrants.