Learning module:

Rights and freedoms Defining Moments, 1945–present

Investigation 1: Exploring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights through key Defining Moments

1.5 1959 Social Services Act

It is 1959.

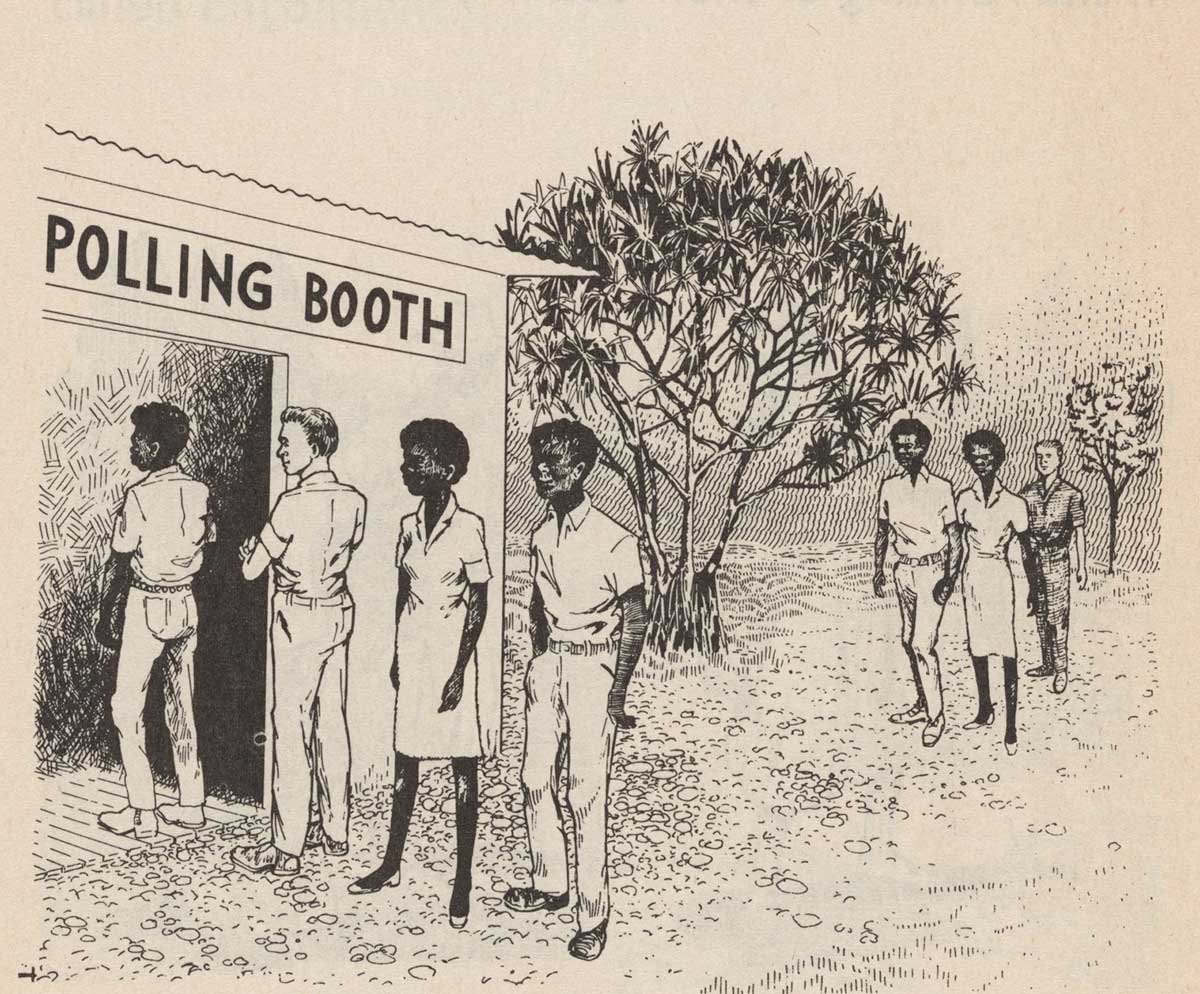

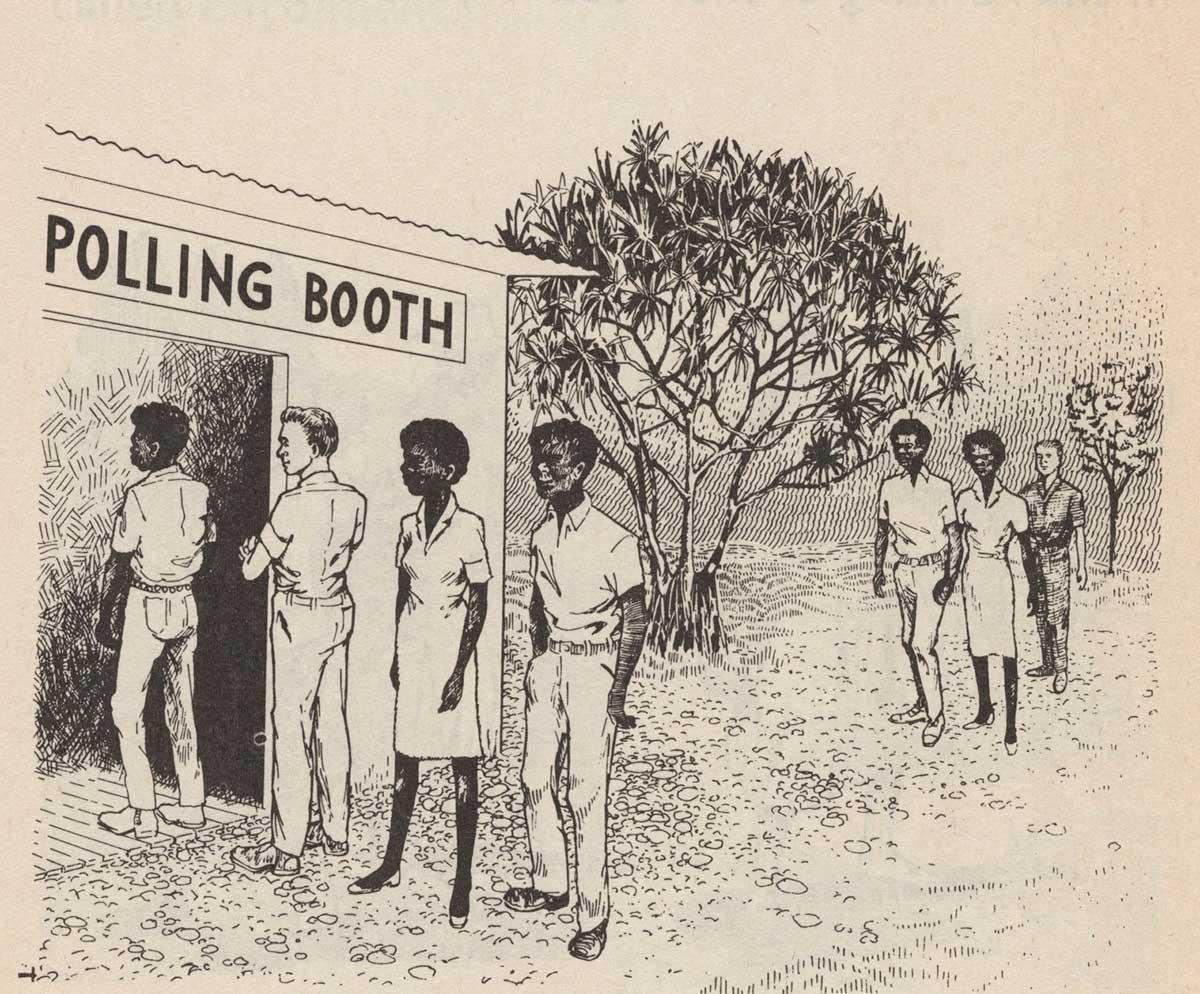

The Australian Parliament is meeting to consider whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians should be eligible for Commonwealth social service benefits, like old age pensions, maternity allowances and invalid pensions.

In the past, when these measures have been introduced, they have been hailed as progressive social justice developments — but they have always excluded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians from their benefits.

Will this Act finally create justice and equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in this area?

Read the information below from the National Museum of Australia’s ‘Collaborating for Indigenous Rights’ on the 1959 Social Services Act and answer the questions that follow.

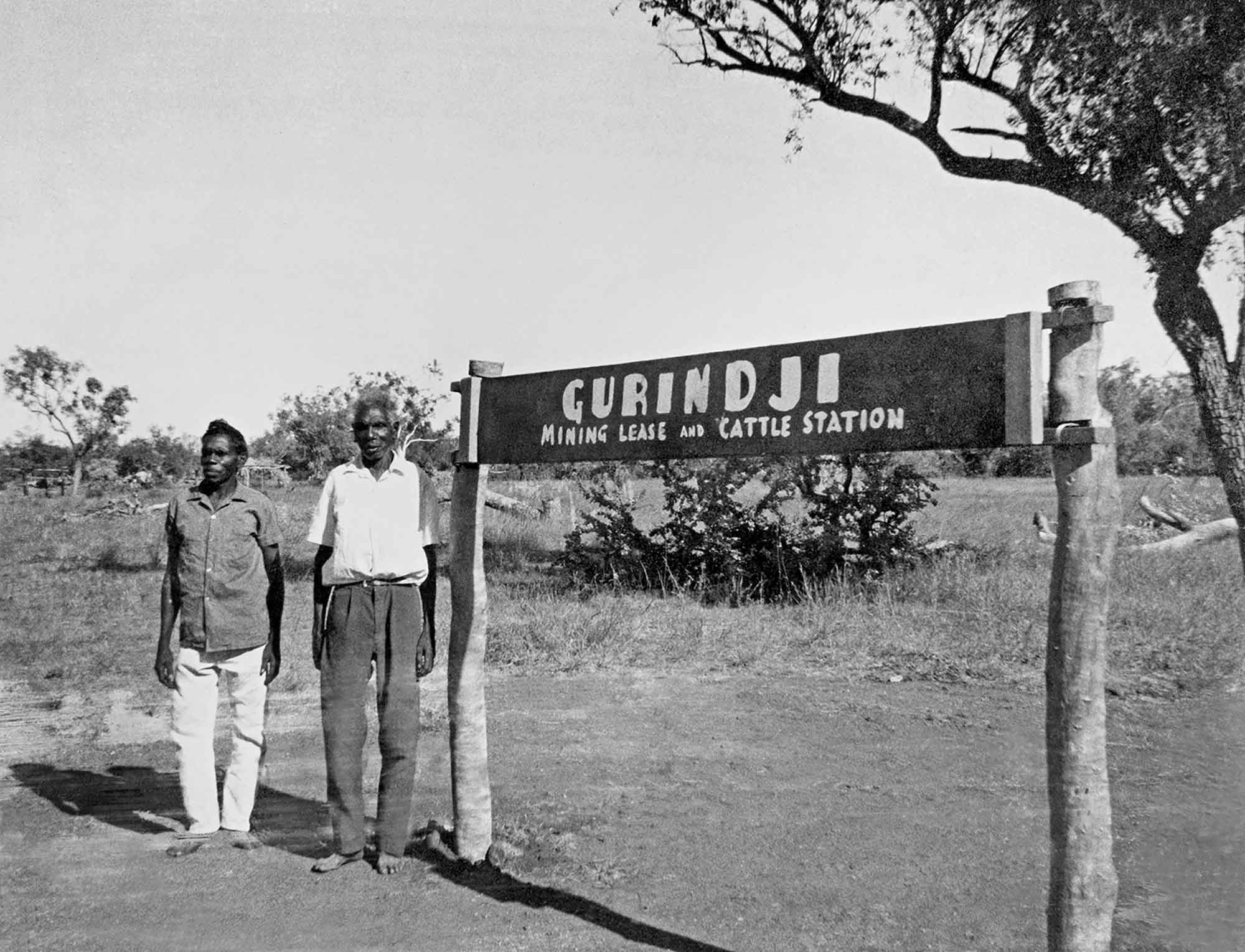

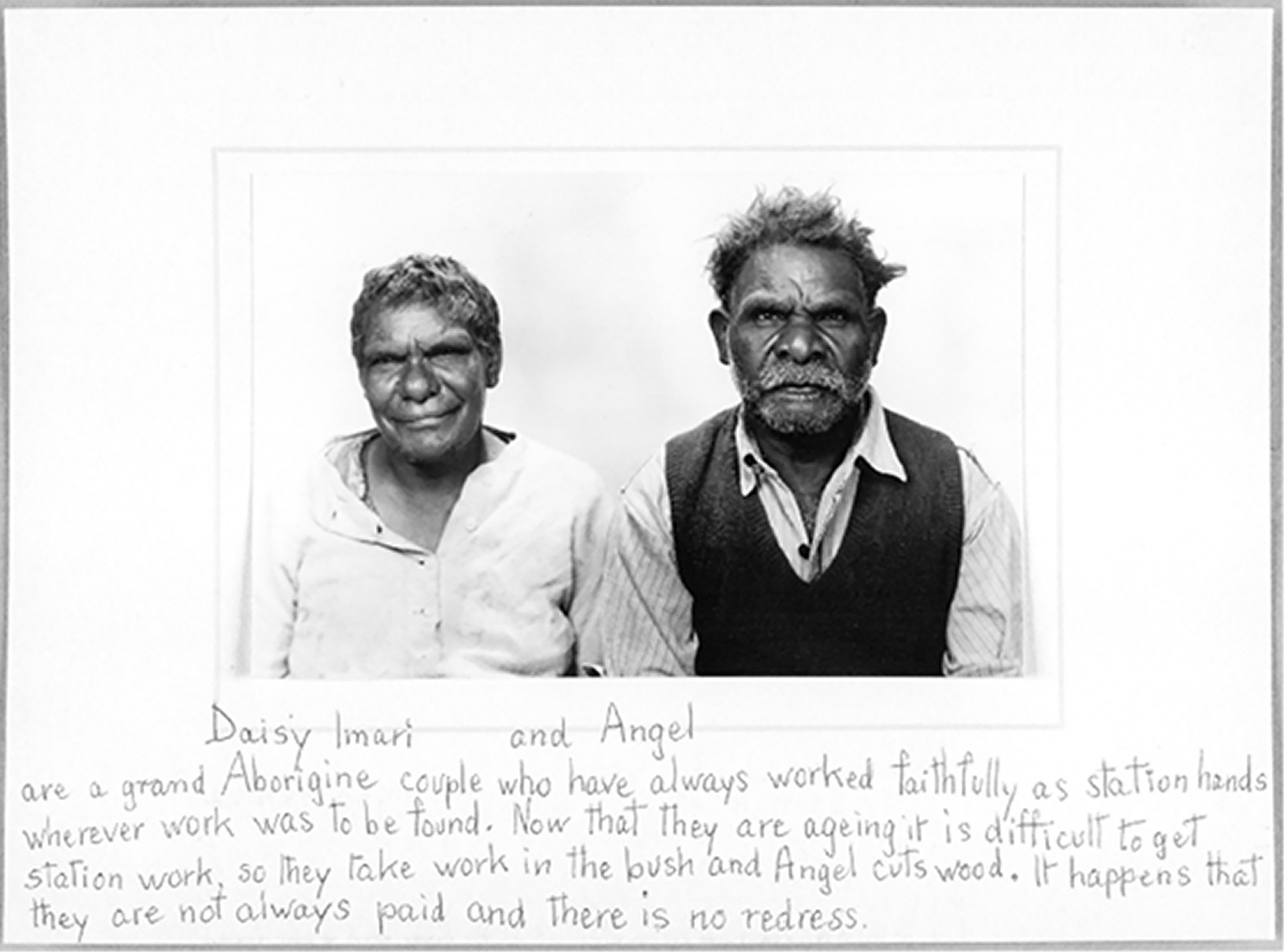

The old age pension and unemployment benefits were not available to Aboriginal Australians in the 1950s. The Social Services Act was amended in 1959 to include them but many impediments remained. Older people had no birth certificates so proof of age was difficult. Most people had not experienced Western education and were illiterate. They often didn’t know that benefits even existed. A further barrier was that, under the amended Act, benefits could not be claimed by people who were nomadic. Many Aboriginal people were, by necessity, workers who travelled from place to place and could be ruled ineligible for unemployment benefits when they were laid off after the muster.

An ongoing cause of dissatisfaction was that even when Aboriginal people were found to be eligible for pensions, they had to apply to the local police officer or magistrate in order to gain access to any of their entitlements.

Activist Shirley Andrews never forgot the story of a young Cairns woman’s experience:

‘I was very affronted to hear the story about this lass. She was a late teenager, she had gone and asked the policemen to buy, she wanted to buy another petticoat, and he said she had one; that was enough. And you know, I was really shocked at that and it was her own money, and what did he think she was going to do when it was in the wash?’

Such situations were common at this time, and for people who had not received an education the assistance of individuals or organisations was necessary if applicants were to have any chance of actually receiving their pensions.

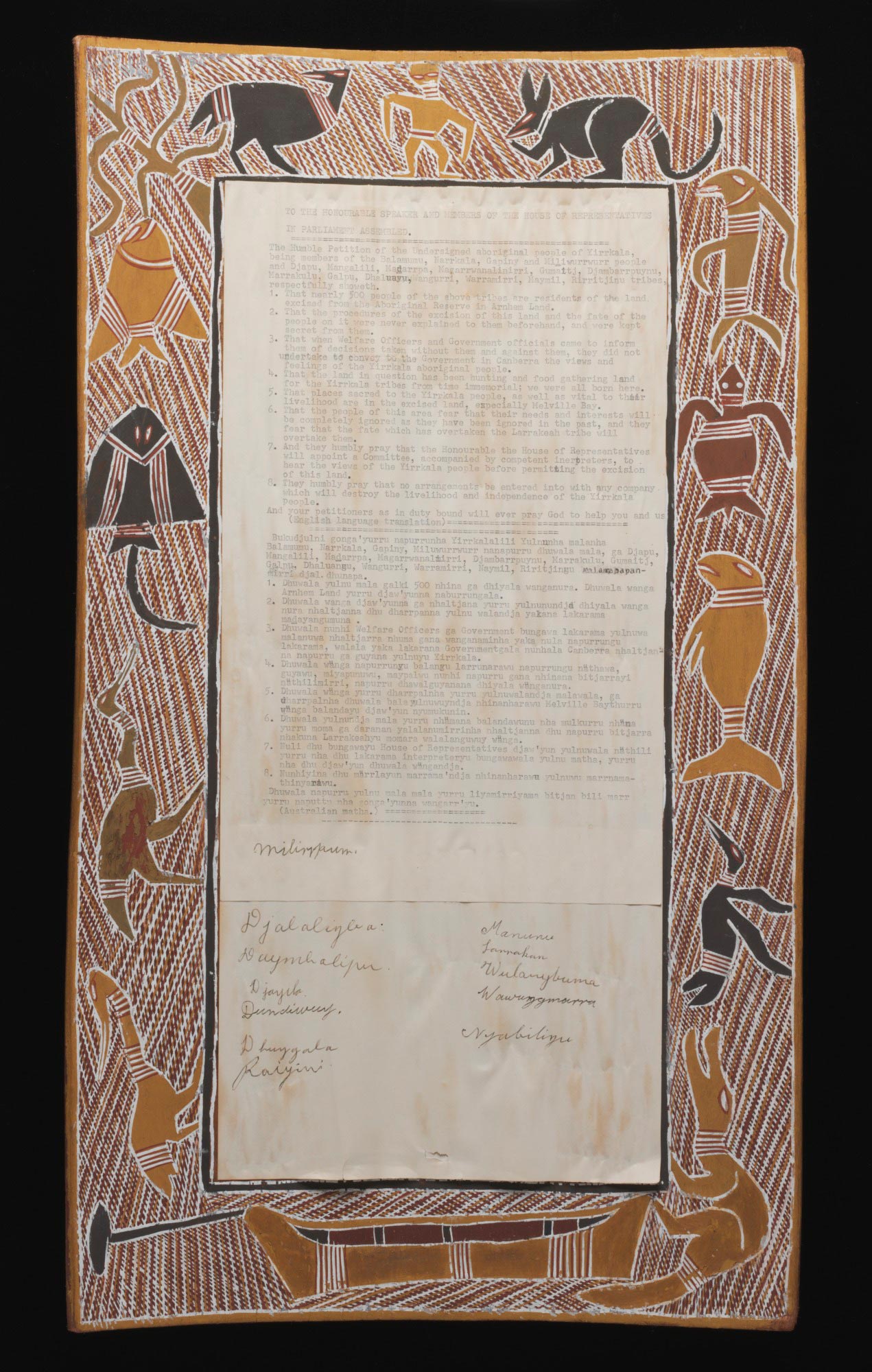

Campaigns in the 1950s by the Victorian Council for Aboriginal Rights, and later by the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement, led to amendments of the Social Services Act 1959, but racial limitations remained. While the new Act repealed the earlier restrictions, it added clause 137a which stated:

‘An Aboriginal native of Australia who follows a mode of life that is, in the opinion of the Director-General, nomadic or primitive, is not entitled to a pension, allowance, endowment or benefit, under this Act.’

The terms ‘nomadic’ and ‘primitive’ were not defined. But Shirley Andrews was quick to point out to the minister that a nomadic lifestyle did not stop other Australians from being eligible for social service benefits. Andrews saw this clause with its undefined terms as a further example of paternalism (restricting the freedom and responsibilities of Aboriginal people, as a father might to a child), which was open to abuse.

In questioning the government’s motives for such an exclusion, Andrews pointed out that people still living a traditional nomadic life would hardly be applying for benefits.

With the passage of the amended Act the campaigning focus took two directions. The first direction was provision of information to Aboriginal people about how to apply for an old age pension or any of the other benefits for which they were now eligible.

In 1963 Shirley Andrews and Rodney Hall (who would later become well known as a novelist) published A Yinjilli Leaflet: Social Services for Aborigines. This leaflet did what the government failed to do; it told Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers what benefits they could apply for and how and where to do this. The leaflet told Aboriginal readers:

‘You have the same rights as other Australians to claim social service benefits.’

The Federal Council distributed this leaflet to missions, reserves and cattle stations across the continent. The fact that many of the people it was addressed to were illiterate, however, meant that mission and reserve managers could control whether the information was passed on.

The second direction was to alert the Australian public as a whole to the fact that most Aboriginal pensioners did not receive the benefits to which they were entitled. Instead their benefits were paid to the missions or reserves where these pensioners lived...

Shirley Andrews pointed out that changing the law was not enough. People who were eligible for a pension but were living on a mission or government reserve were not paid directly. Instead the money went to the institution. This system was open to abuse and mismanagement.

A further valuable contribution which Andrews made to public knowledge was the data she compiled in, The Australian Aborigines: A Summary of their Situation in all States in 1962. This showed the many state laws governing people, variously defined by state governments as ‘Aborigines’, and the limitations to their rights — to move, to marry, to rear their children, to handle their earnings or to own property. This was circulated to interested bodies and provided the clear evidence of legislation which robbed people of basic rights. For example, in Queensland at this time the letters of Aboriginal people living in missions could be legally opened before being passed to the recipient. Shirley Andrews’ document was most likely the first attempt to make much needed information available to the public, at a time when the numbers of vocal critics of government failures in Aboriginal affairs was growing. It also strengthened the argument for encouraging the Australian Parliament to take a more active role.

Edited from Social Service benefits, 1954–64, Collaborating for Indigenous Rights, National Museum of Australia https://indigenousrights.net.au/civil_rights/social_service_benefits,_1…, viewed 14 October 2020

1. When was Australian law amended to include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in social welfare payments?

2. Why do you think Aboriginal people had been denied this citizenship right since the first social welfare payments in 1902?

3. What difficulties still existed for Aboriginal people to actually exercise their new citizenship rights?

4. What campaigns were carried out to let people know about their rights?

5. One of the campaigners was Shirley Andrews, someone whose name you may have never heard before. Why do you think she might be an unknown hero in Australian history?

6. Andrews said that her reason for her activities was:

‘Our ancestors have left us an unpaid debt to these people, and we must make a special effort to carry out our responsibilities, not with any spirit of “doing good”, but as a duty long neglected.’

What does Shirley Andrews mean by ‘a duty long neglected’? Why did she consider this important?

7. Why might some people in Australia at the time have thought that the lack of full citizenship rights to Aboriginal people was not an important issue?

8. The actions taken by the government towards Aboriginal people at the time is called ‘paternalism’. What is paternalism? Why might it exist?

9. What was the significance of the Social Service Act for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights?

10. How would this event have influenced the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights over time?