Learning module:

Rights and freedoms Defining Moments, 1945–present

Investigation 1: Exploring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights through key Defining Moments

1.1 Your task

Since 1945 there have been many developments in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights in Australia.

Reactions to these have varied. A number of these changes have been controversial and contested, while some civil rights discussions are ongoing and unresolved.

Your task is to examine 27 of these key developments in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights in Australia and use your findings to evaluate the significance of these Defining Moments. To do this you will need to:

1. Understand the background to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights by 1945.

2. Examine 27 Defining Moments in Australian history related to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ rights and freedoms. Your teacher may decide to distribute these among the class.

For each event you need to:

- Read and understand the key elements of the situation by answering the questions listed with each Defining Moment.

- Think about how this Defining Moment impacts on the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights: has it helped it, obstructed it and/or opened up new areas and possibilities?

3. When you have looked at each of the Defining Moments, analyse the outcomes and impacts for each and decide which you think are the most important or significant.

4. Share your ideas with your classmates and then create a whole of class list of the most important Indigenous rights Defining Moments.

5. Then decide as a class which current Indigenous rights issues might become the next Indigenous rights Defining Moments and justify your choices.

6. Finally, complete the quiz to help you consider what this investigation has taught you about this aspect of Australian history.

To help you get started, read the Background Briefing of the state of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights up to 1945.

Background Briefing: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights to 1945

1788–early 1900s

Australia’s Indigenous peoples represent the oldest continuing cultures on Earth, and there are over 300 distinct Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural groups. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples inhabit all parts of the Australian continent, including 38 Torres Strait islands, as they have done for thousands of years.

Each group has its own language, laws, rituals, beliefs, traditions, tools and weapons — its own culture.

Prior to 1788 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups traded and met for special ceremonial occasions, recognising individual groups’ territory, or country. They managed natural resources according to the seasons and a complex understanding of the landscape. Some communities built permanent dwellings, while others travelled vast distances over their country according to hunting and growing seasons. Many of these cultural practices continue today, and this connection to country is reflected in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, languages, traditional practices and stories.

When Europeans arrived they rapidly expanded into Aboriginal territories, bringing with them new diseases and an appetite for the acquisition of land. Many times there was conflict resulting in terrible consequences, especially for Aboriginal people. Occasionally there was cooperation but this was often necessitated by the growing imbalance in the relationship between Europeans and Aboriginal people. The overall impact of the European spread was to disrupt and endanger Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures.

Later, governments and missionaries established missions and protectorates, partly out of a concern for the fate of Aboriginal people but also partly in an effort to ‘Christianise’ them. As a result, these further threatened Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, while also imposing restrictions on movement and behaviour that did not apply to European settlers.

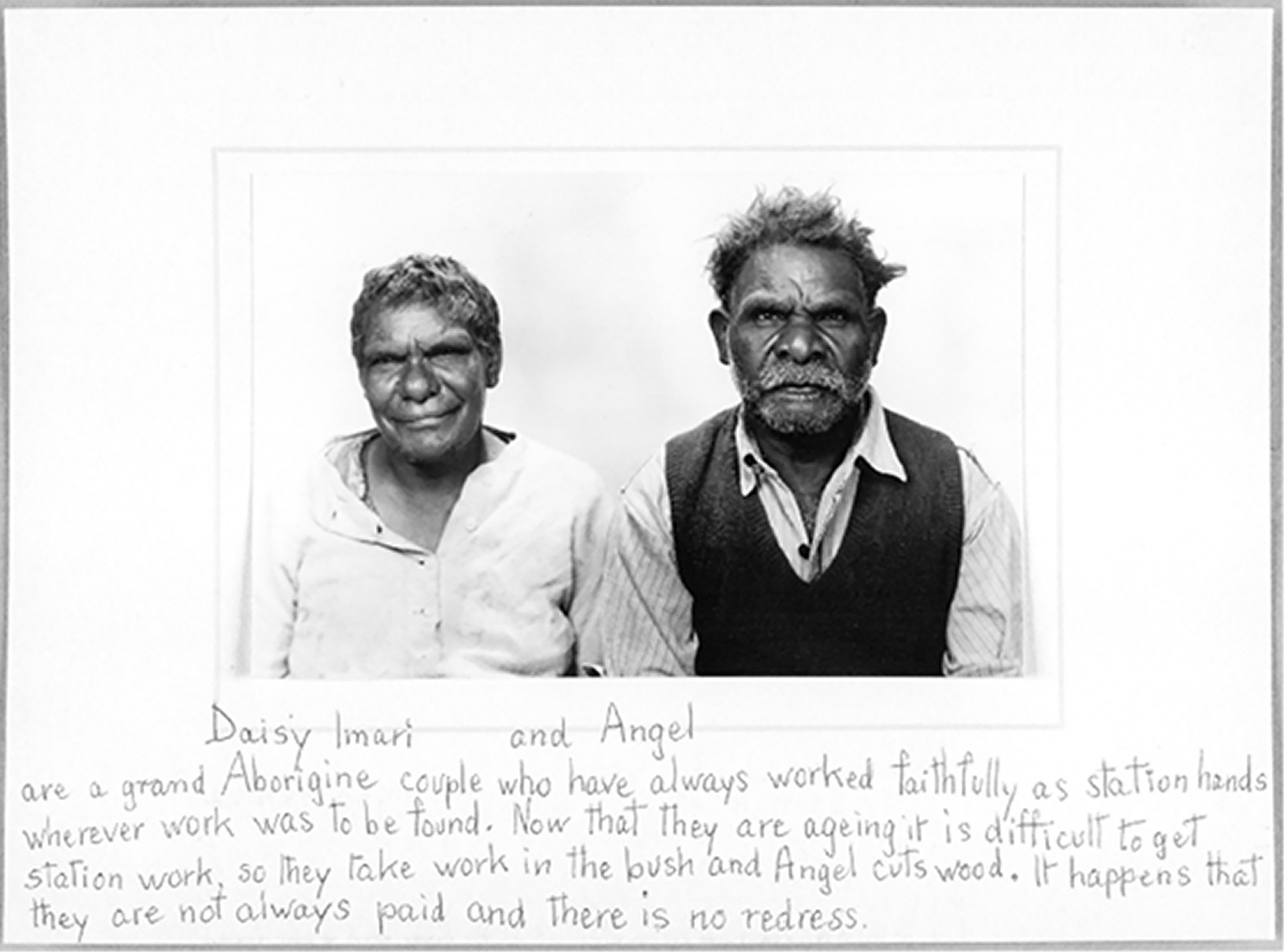

In some states and territories Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living on missions and protectorates were unable to marry freely. For example, Aboriginal women were unable to marry non-Indigenous men in the Northern Territory from 1918. Further, Aboriginal children were increasingly taken from their parents as a result of new laws passed by governments and enforced by authorities. Other rights, such as the opportunity to own property, were also denied in most states.

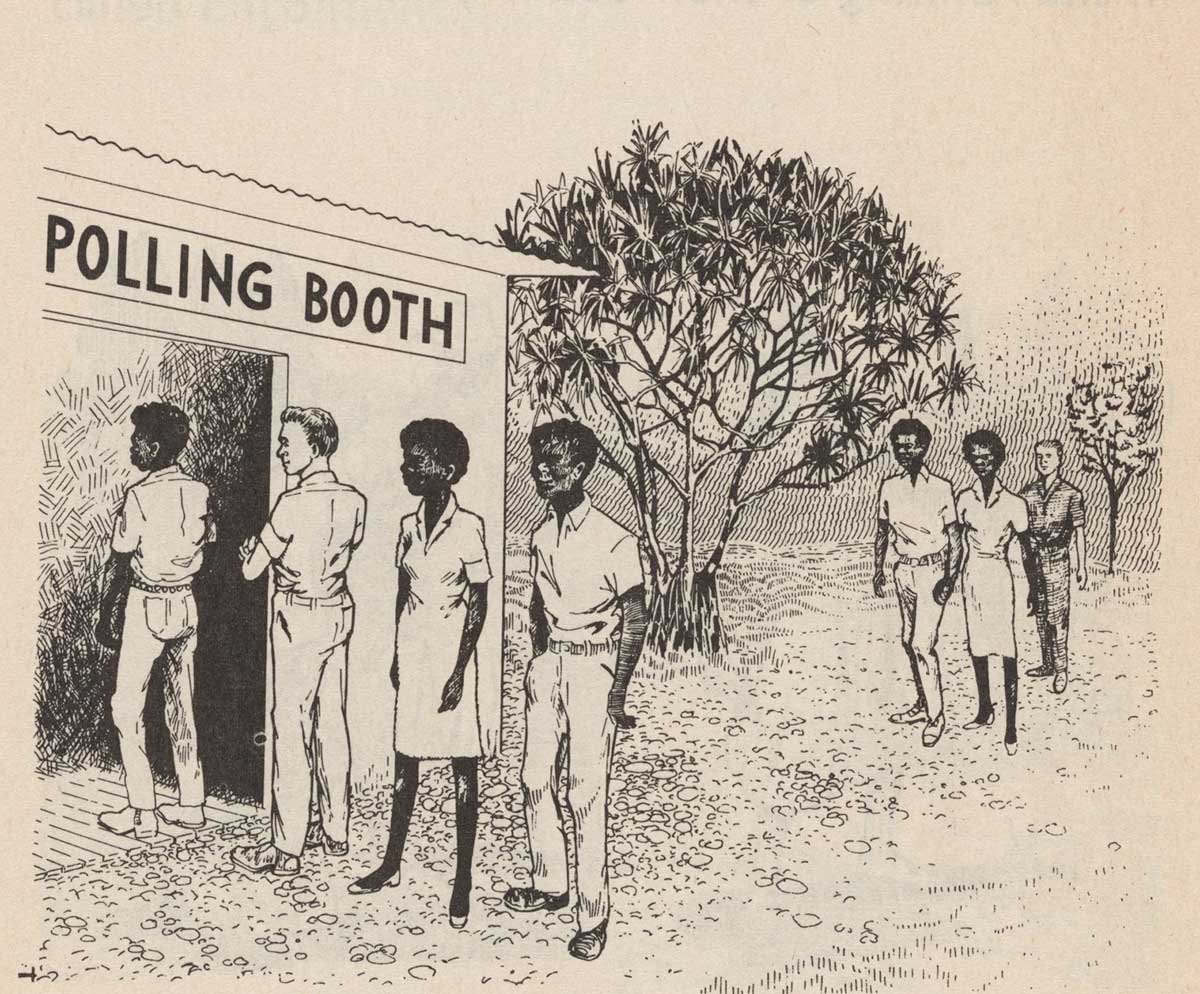

As the colonies developed their political and civil rights, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and other non-Europeans were often excluded from these rights. For example, Aboriginal men could vote in most colonies as they were automatically included in the male franchise laws, except in Queensland and Western Australia. Aboriginal women could vote in South Australia from 1894, but not in the other colonies. The majority of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people could not vote in federal elections until 1962.

Early 1900s–1960s

Conflict on the frontiers of European expansion continued into the twentieth century. The last recorded massacre of Aboriginal people occurred in 1928 at Coniston. Despite a royal commission investigation being held into these events, none of the non-Indigenous people involved in the killings were held responsible.

When Australia was called upon to fight in the First World War, over 1000 Aboriginal men volunteered, however only a handful of those who returned from the war were considered for soldier settlement farms. During the 1920s and 1930s demands for equal citizenship rights began to get stronger with a number of prominent Aboriginal leaders emerging along with the beginnings of political agitation and organisation. Activists such as Fred Maynard, Jack Patten and Pearl Gibbs were instrumental in raising awareness of Indigenous rights issues during this time. In 1938, when celebrations were held for the 150th anniversary of the landing of the First Fleet, a group of Aboriginal leaders declared it a Day of Mourning, not of celebration, and published demands for citizenship equality.

Despite this lack of citizenship equality, over 3000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women served in the Second World War. During this period many Aboriginal people received full and equal wages for the first time, gained the respect of others, and saw examples of equality that had not existed before. At the end of the war Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men who had served overseas were eligible to vote in federal elections. But many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continued to experience social exclusion and discrimination, especially in country towns, and wage and social services inequality.

Even as late as 1962, the Federal Council for Aboriginal Affairs reported that the situation facing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on missions with respect to civic rights was at best uneven and at worst highly discriminatory.

This table shows the rights available to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in different states and territories in 1962:

|

Civic rights |

NSW |

VIC |

SA |

WA |

NT |

QLD |

|

|

Vote in state elections |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Marry freely |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

|

|

Control own children |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

|

Move freely |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

|

Own property freely |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

|

|

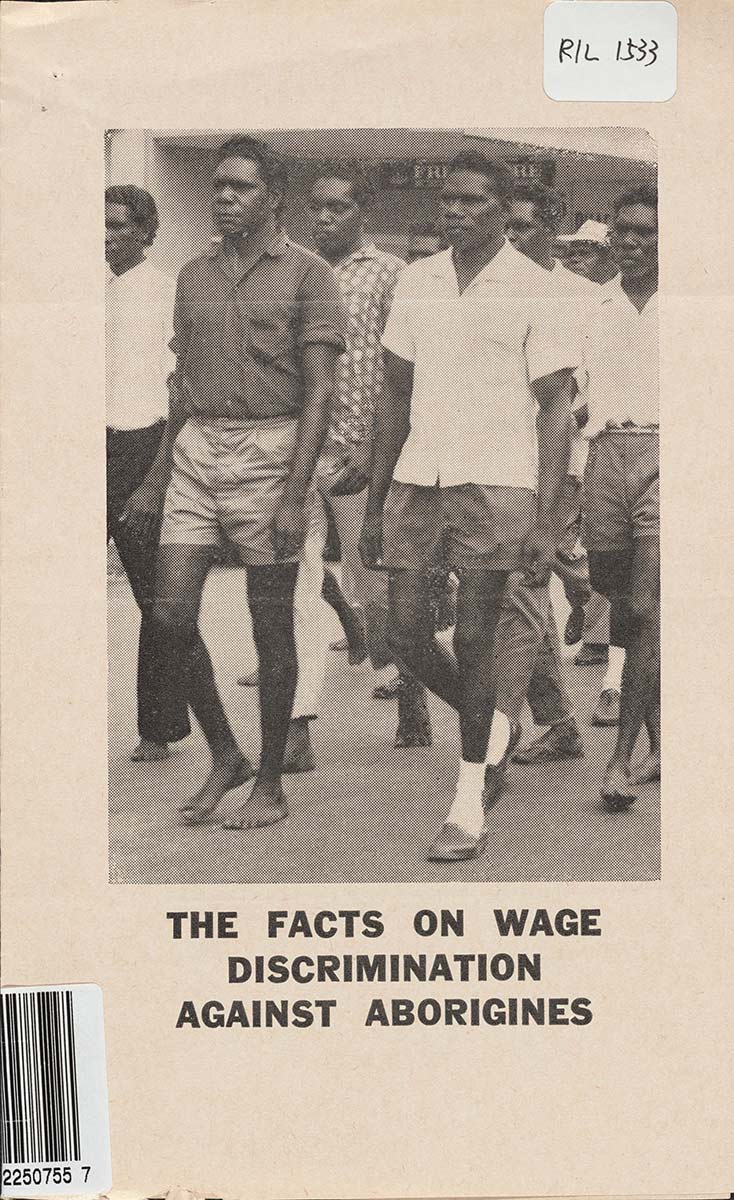

Receive award wages |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

|

Alcohol allowed |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

|

Note: There is no data available for Tasmania.

‘The Australian Aborigines: a summary of their situation in all states in 1962’, prepared by Shirley Andrews, campaign organiser, Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement

Source: Box 3/4, Council for Aboriginal Rights (Vic.), Papers, MS 12913, State Library of Victoria

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

In 1948 the new world body, the United Nations, published its Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This declaration reflected the developments in human rights over hundreds of years, dating back to the rights established in Magna Carta in 1215, through the development of parliamentary democracies, of the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolutions, the British, French, American and Russian Revolutions, the Industrial Revolution, and the war against fascism and totalitarianism.

In the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, rights and freedoms received their most concise description to date.

How would Australia respond to this international expectation of equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people?

Here are 28 key Defining Moments to help you understand the path that the many developments in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights in Australia have taken.

Investigate each of these by reading the explanations and answering the questions that follow. Your teacher may decide to distribute these Defining Moments among the class.