Learning module:

Rights and freedoms Defining Moments, 1945–present

Investigation 1: Exploring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights through key Defining Moments

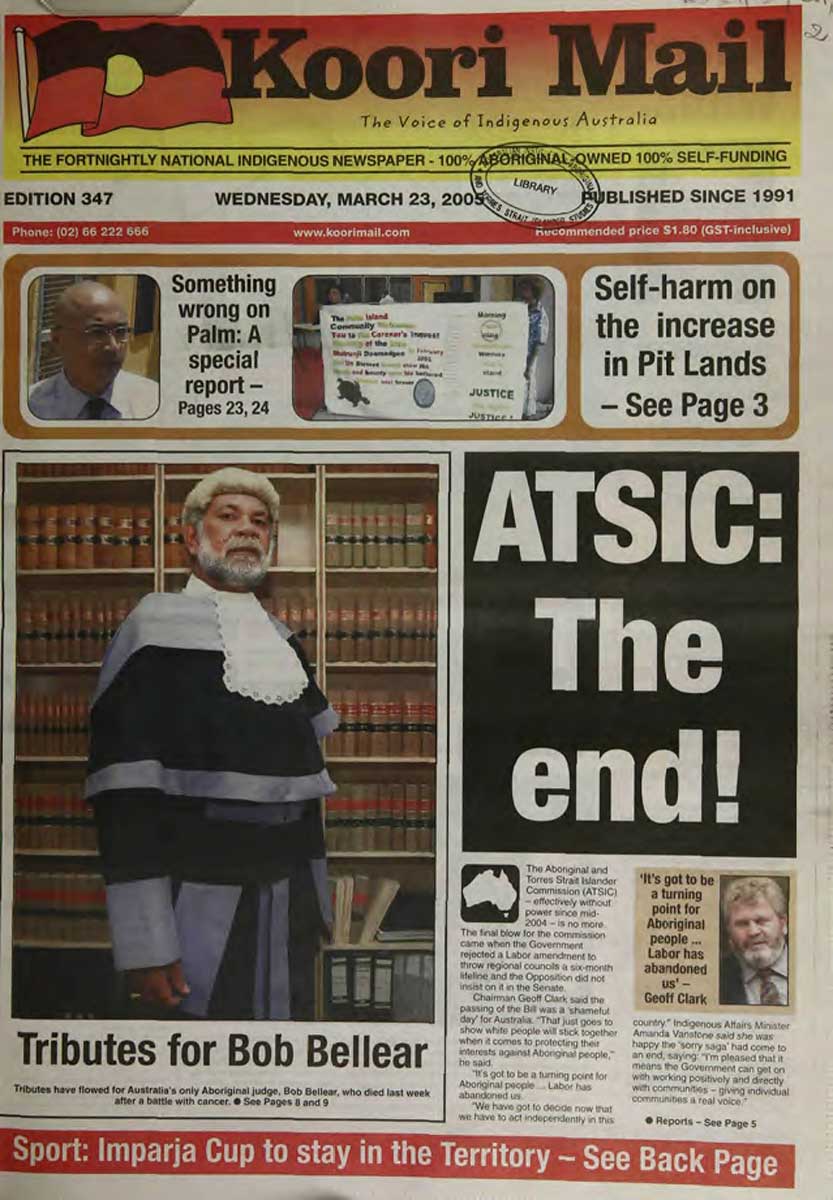

1.24 2005 Abolition of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC)

It is 2005.

The body that has provided an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice to the Australian Government, ATSIC, is to be abolished.

It has become a flawed advisory body, subject to financial corruption, and not truly representative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

But its abolition raised the question: was a special Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice needed?

Read the information below, from a report written at the time of the 2005 Abolition of ATSIC, and answer the questions that follow.

[One] of the key roles of the ATSIC Board, and its two precursors, the National Aboriginal Consultative Committee (NACC) and the National Aboriginal Conference (NAC), was to advocate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on various issues. In particular, these bodies were active in advocating and promoting debate on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander political rights issues.

[With its abolition,] it is now unclear what, if any, representation Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population will have in international forums previously attended by ATSIC representatives.

Is there no place for an elected body in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs? Is there a public relations aspect to the continuance of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s right to elect an organisation made up only of their own people? For a government, there might be more to be lost in its relations with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community than would be gained if this franchise right were taken away ... Creation of such a body might be less troublesome for a government than having prominent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people refusing to join an advisory body. One ATSIC Commissioner has suggested that such people would be seen by their peers as government lackeys, and has warned that the people will not recognise them.

With ATSIC’s demise it is now pertinent to ask: just what is the place of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in the political system? From one standpoint, the opportunity now exists for repairing what is seen as earlier damage to the political system. Former Liberal Minister for the Environment, Aborigines and the Arts (1971–2), Peter Howson, claims that elected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representation is no longer justified, and that politically Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population should be treated the same as other Australians. In response to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander claims that this would be to head back towards the pattern of assimilation, wherein the policy goal would be to assimilate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians into the mainstream society, Howson claims it would in fact accord with the realities of modern Australian society:

‘The majority of Aborigines [sic] are part of the wider community. Their extensive integration [into Australian society] is reflected in the 70 per cent now married to non-indigenous spouses and professing Christianity, in the majority being of mixed descent, and in almost all speaking a non-indigenous language at home; more than 70 per cent live in urban areas and Aboriginal employment rates there are not markedly lower than for others.’

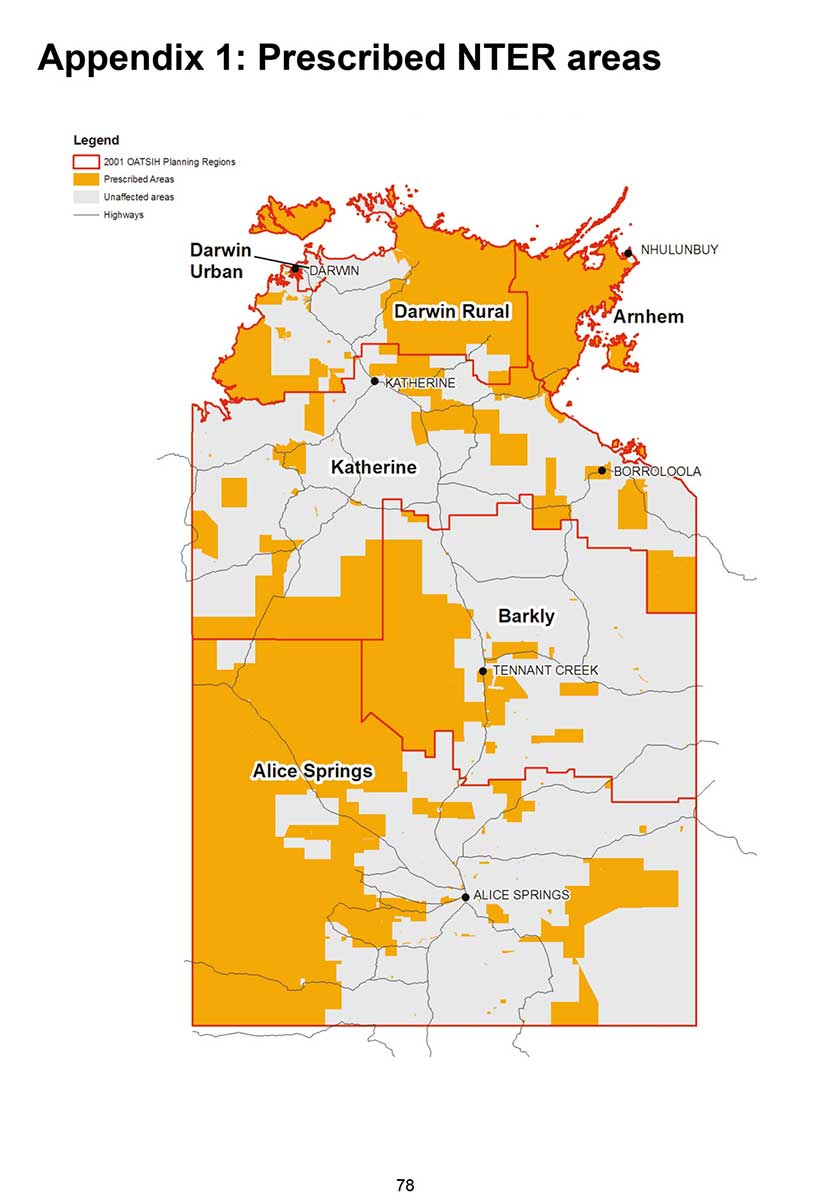

While his data may be correct, Howson’s view ignores the symbolic importance of the fact that successive governments have continued to reaffirm that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a place in the nation that is different from the vast majority of citizens. This is partly because of their status as the first inhabitants, and partly as the consequence of their requiring particular assistance from government. By any yardstick Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s conditions of living fall well behind those of the rest of the Australian population. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner’s Social Justice Report 2003 has made this quite clear. In a wide range of indicators this could be measured: infant mortality, life expectancy, participation in the workforce, education retention rates, incarceration rates and child abuse figures are just a few.

Angela Pratt and Scott Bennett, The end of ATSIC and the future administration of Indigenous affairs, Current Issues Brief no. 4, 2004–05, Parliament of Australia

1. What was ATSIC?

2. What was its main role?

3. Why was it abolished?

4. What impact did this have on the representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues to the Australian Government?

5. Why do some see an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice as unnecessary?

6. Why do some see an Indigenous voice as essential?

7. What was the significance of the abolition of ATSIC for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights?

8. How would this event have influenced the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights over time?