Learning module:

Making a nation Defining Moments, 1750–1901

Investigation 1: Contact and conflict

1.6 Case study: Frontier conflict perspectives

Introduction

In 1864 there were several clashes between European explorers and local Aboriginal people in the Roebuck Bay area of Western Australia, near modern-day Broome. These resulted in the deaths of both explorers and local Aboriginal people.

Imagine that you have been approached by descendants of some of those killed to create two memorial plaques.

The descendants have given you two packages of information. You need to use both packages to complete your task.

Work out the answers to these questions:

- Who is this plaque being created for?

- When were they killed?

- Where were they killed?

- Why were they there?

- How and why were they killed?

- Why is a memorial being dedicated to them? Why were they significant?

Take notes as you read the evidence files in the two packages and then answer the questions below. You will need to read all the evidence files for each package. Then use your notes to create the final memorial plaques.

You have limited space for each memorial plaque, so be accurate but also concise. The descendants are relying on you to create something that they can be proud of.

|

Skip to Evidence package B |

Evidence package A

Your task:

- Study everything in Evidence set A, making notes as you go

- Look at the questions in Evidence notes A

- Use your notes to create Memorial plaque A

Evidence set A

| A1 Background information |

A2 Location of Roebuck Bay |

A3 Some information about the European explorers |

A4 Roebuck Bay Pastoral and Agricultural Association Limited |

| A5 From the journal of FK Panter |

A6 Witness Peir ding marra |

A7 Maitland Brown |

A8 ‘Murdered in their sleep’ |

Evidence A1

Background information

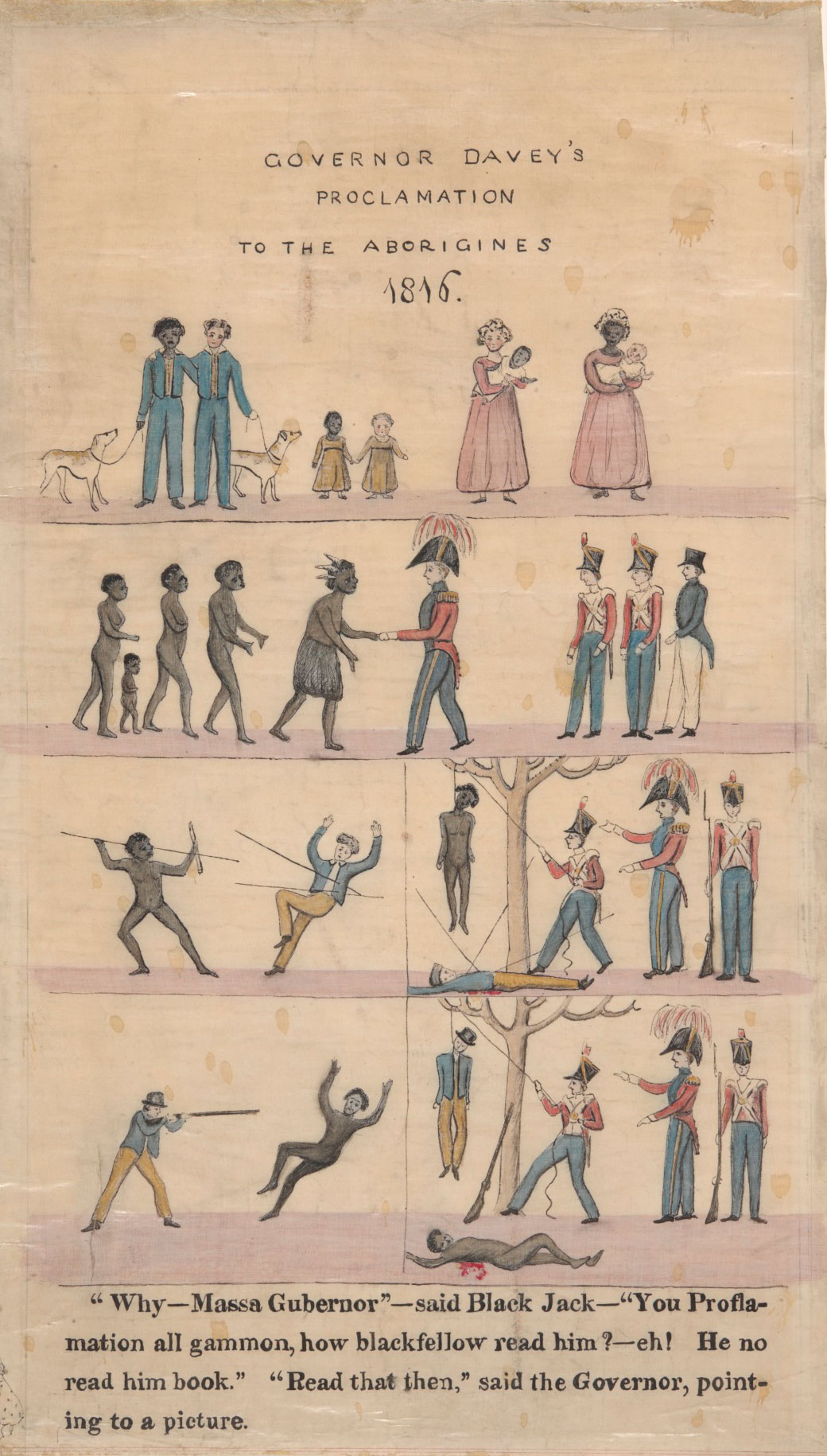

By 1864:

-

Aboriginal people had lived in and around the Roebuck Bay area of Western Australia, near modern-day Broome, for thousands of years.

- European pastoralists wanted to move into these areas with their animals.

- Explorers had been in the area previously to find good pastoral land.

- Explorers had clashed with Aboriginal people before the 1864 expedition in the Broome area.

- The 1864 expedition was searching for good pastoral land.

- The 1864 group clashed with Aboriginal people during their search.

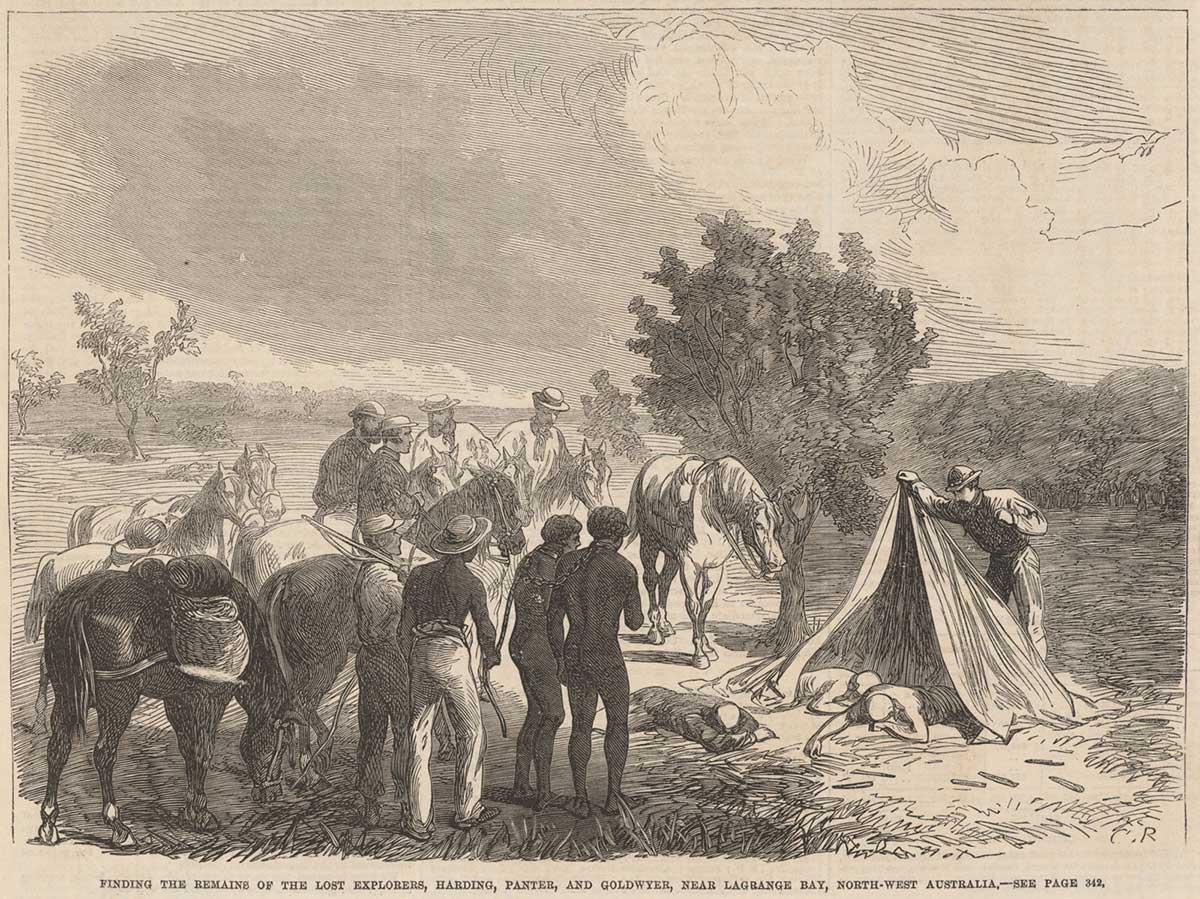

- Three explorers were killed by Aboriginal people.

- Four months later a new expedition, led by Maitland Brown, came to the area to find out what had happened to the missing explorers.

- There were clashes with Aboriginal people during and after the search and many Aboriginal people were killed.

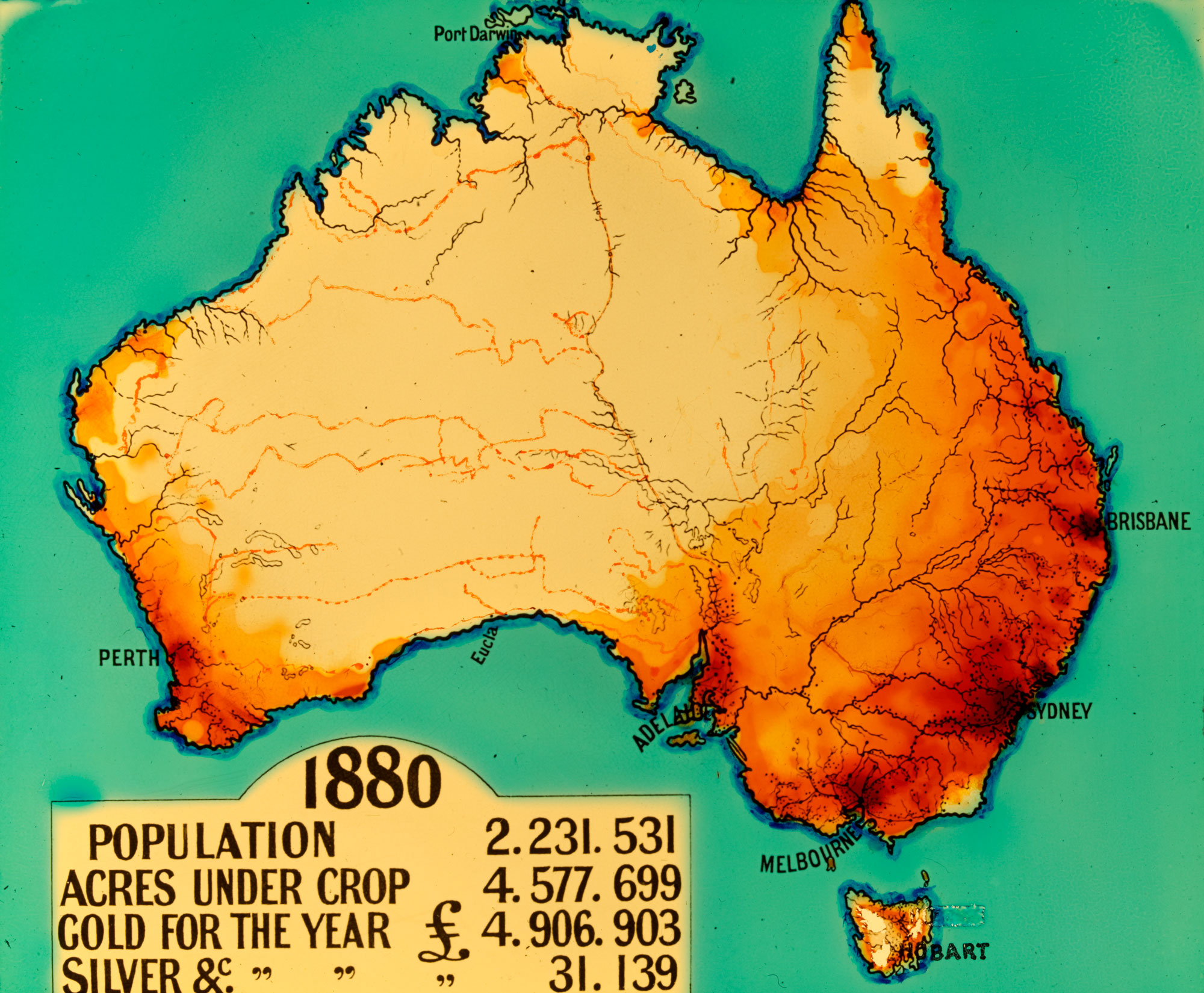

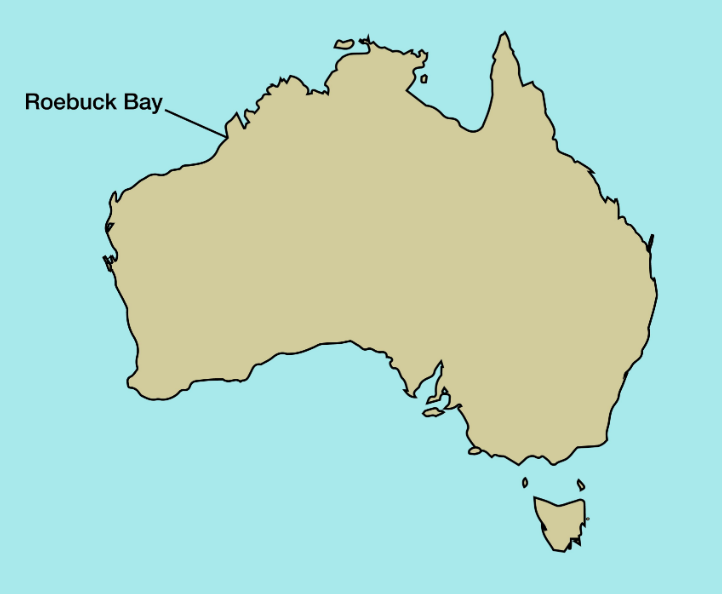

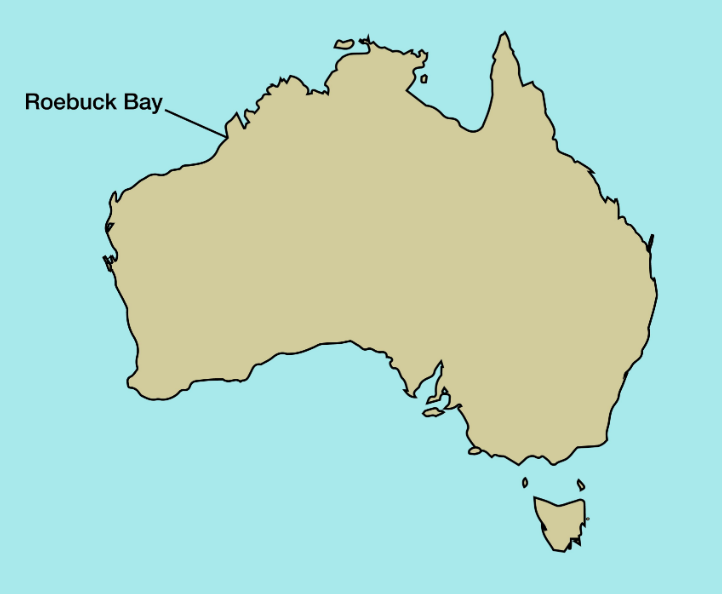

Evidence A2

Location of Roebuck Bay

Evidence A3

Some information about the European explorers

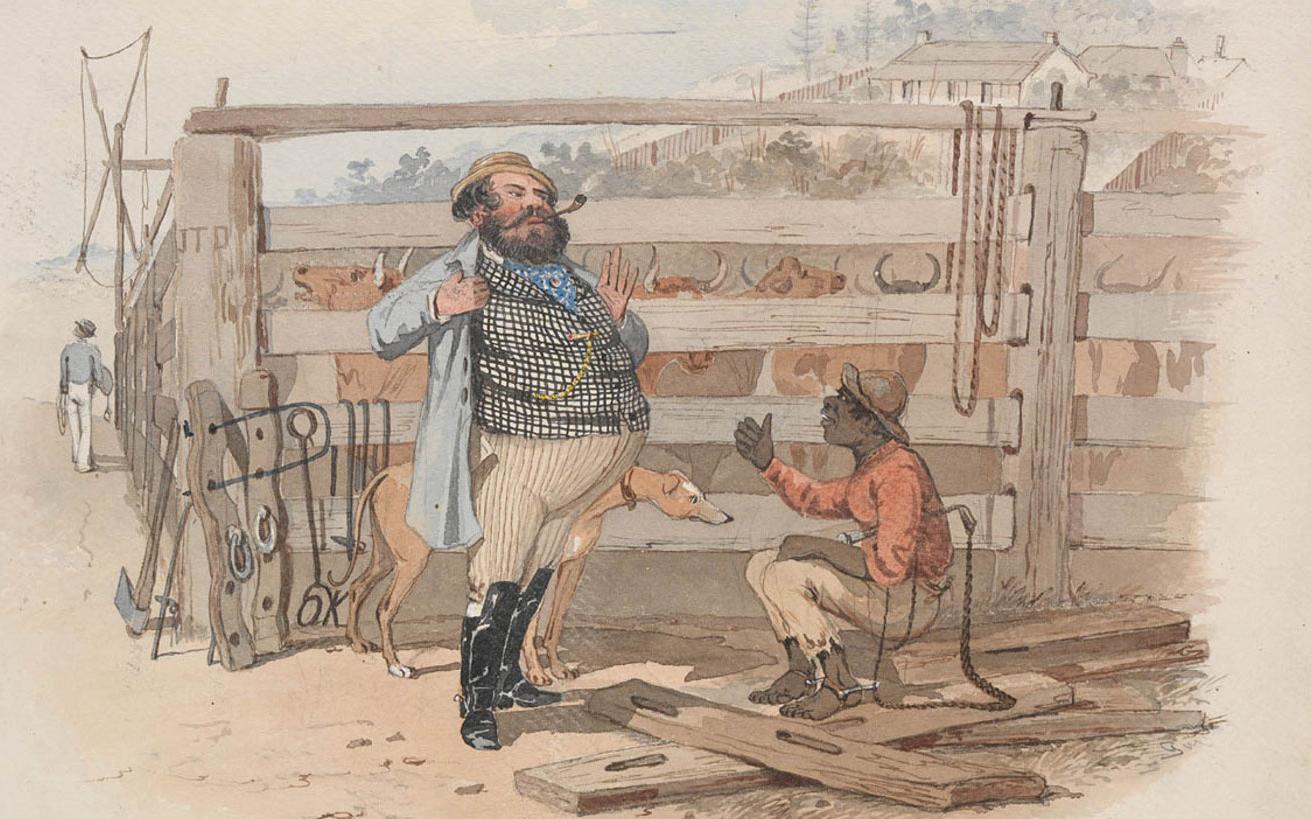

- Frederick Panter, born 1836, was an employee of the Roebuck Bay Pastoral Company. He had visited the area previously.

- James Harding was born in 1838 in England, and had emigrated with his family to Western Australia in 1846. He was to be the manager of the new settlement.

- William Goldwyer, born 1829 in England, was a sergeant of police, and had a wife and three children.

- They were experienced explorers.

Erickson, R., 1988. Bicentennial Dictionary of Western Australians, pre-1829-1888, vols 2 and 3

Evidence A4

Roebuck Bay Pastoral and Agricultural Association Limited

The object of the Association is to promote the colonisation of the recently explored country on the North-West Coast, by the formation of establishments and stations in localities best adapted for depasturing stock.

It is proposed, in the first instance, to secure sufficient land in the vicinity of Roebuck Bay for the purpose of the Association.

Roebuck Bay is selected because the land near the sea coast, and for many miles inland, has been declared by recent travellers to be admirably adapted for sheep; because there are facilities for landing stock; because water is easily obtainable in sufficient quantity; and because change of feed and situation may be easily obtained by securing some of the equally available country on the range of hills leading form Roebuck Bay to Dampier’s Land.

Inquirer, 3 August 1864.

Evidence A5

From the journal of FK Panter

November 12th 1864: Started at daylight across the plains for 6 miles, all of which was well grassed with 5 kinds; came to a [place] with water 10 inches from the surface and, I have no doubt, in some places on it; trees 50 – 60 feet high almost perfectly straight; at 3 miles farther came to a small lake (5 acres) with beautiful fresh water, thousands of cockatoos, ducks, & c., shot four. In the afternoon Mr. Harding and myself found more swamps at 3 miles distant in a S.E direction, there was not much water in them but splendid grass all round; we also found several strong springs...; kangaroo tracks very numerous; returned to camp before sunset; saw 12 flamingoes.

Nov. 13: Remained in camp. Early in the morning – natives came to us; gave them 5 cockatoos and 5 pigeons; they left soon after but in an hour returned with spears, &c., and as they appeared to be up to some mischief we frightened them away by firing a revolver; they kept whispering and making signs we could not understand. In another hour we again saw them sneaking behind some bushes, but when seen they ran away.

Perth Gazette and WA Times, 12 May 1865

Evidence A6

Witness Peir ding marra

11 March 1865: A native named Peir ding marra came a few days from the east, and told me that about four months ago three white men with four horses were seen one night about ten days journey to the eastward of this, by the Wiogararry tribe of natives, at a river called Boolu boolu; the white men slept there that night and next morning proceeded in this direction, but during the day were met and attacked by the natives who saw them the night before with others but the white men immediately shot and killed three of their number which caused the rest to run away; the white men did not come any further this way but returned that day to their camp of the night before, which was on a level plain near the bank of the river; to this place the natives followed them keeping out of sight, and then watched them until all fell asleep when with increased numbers stole upon them, stuck spears throw them all and tried to keep them pinned to the ground, but without success as they got on their feet in spite of their wounds and all the efforts made to prevent them, and killed fifteen of the natives and succeeded in driving the rest away.

These knowing the white men to be mortally wounded, collected more natives who were all through the night gathering from all quarters, and returned before daylight this time overpowering the white men who were unable to offer much resistance, by rushing upon them with spears and clubsticks.

The next day they killed the horses with clubs. They have not touched an article belonging to the white men.

Maitland Brown to Colonial Secretary De Grey River, 11 March 1865. CSR Acc 36, vol. 555, pp 169-70, Battye Library

Evidence A7

Maitland Brown

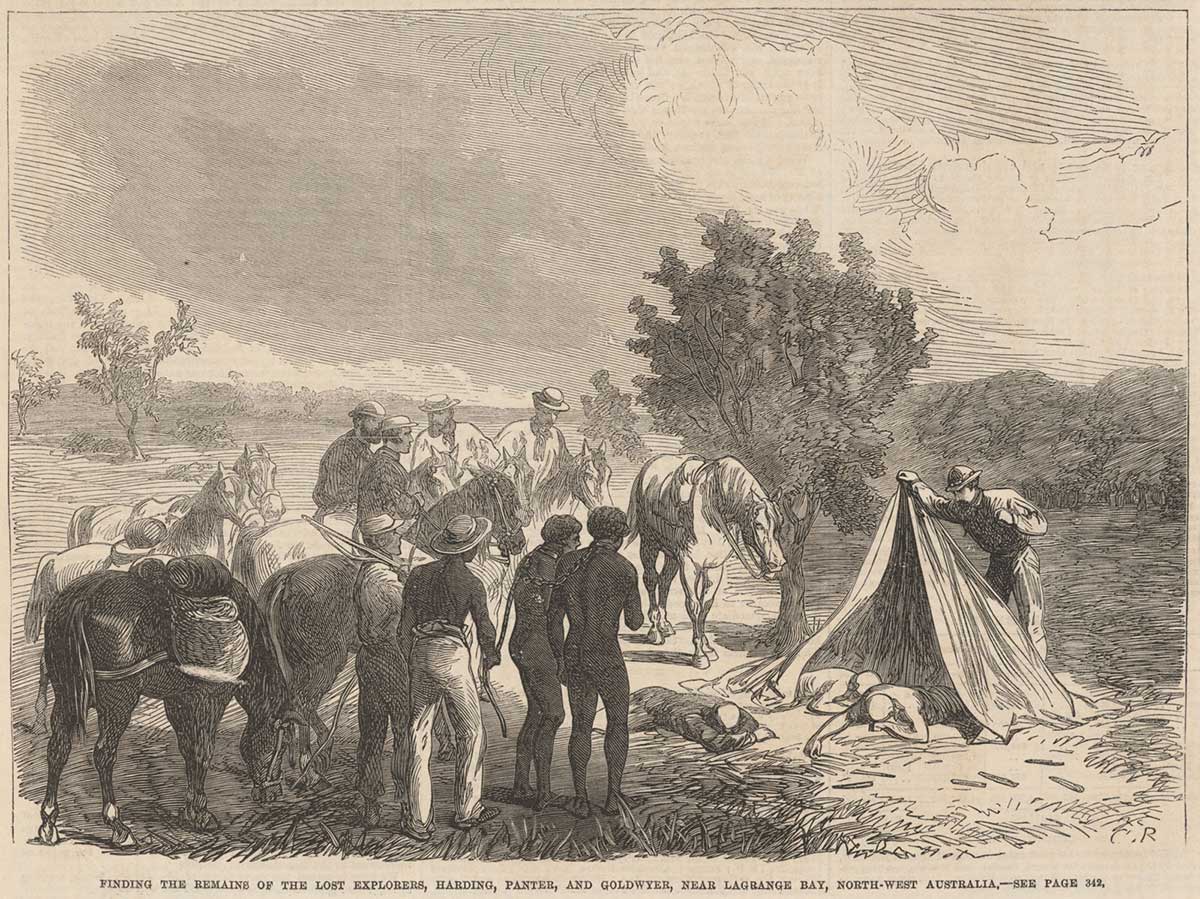

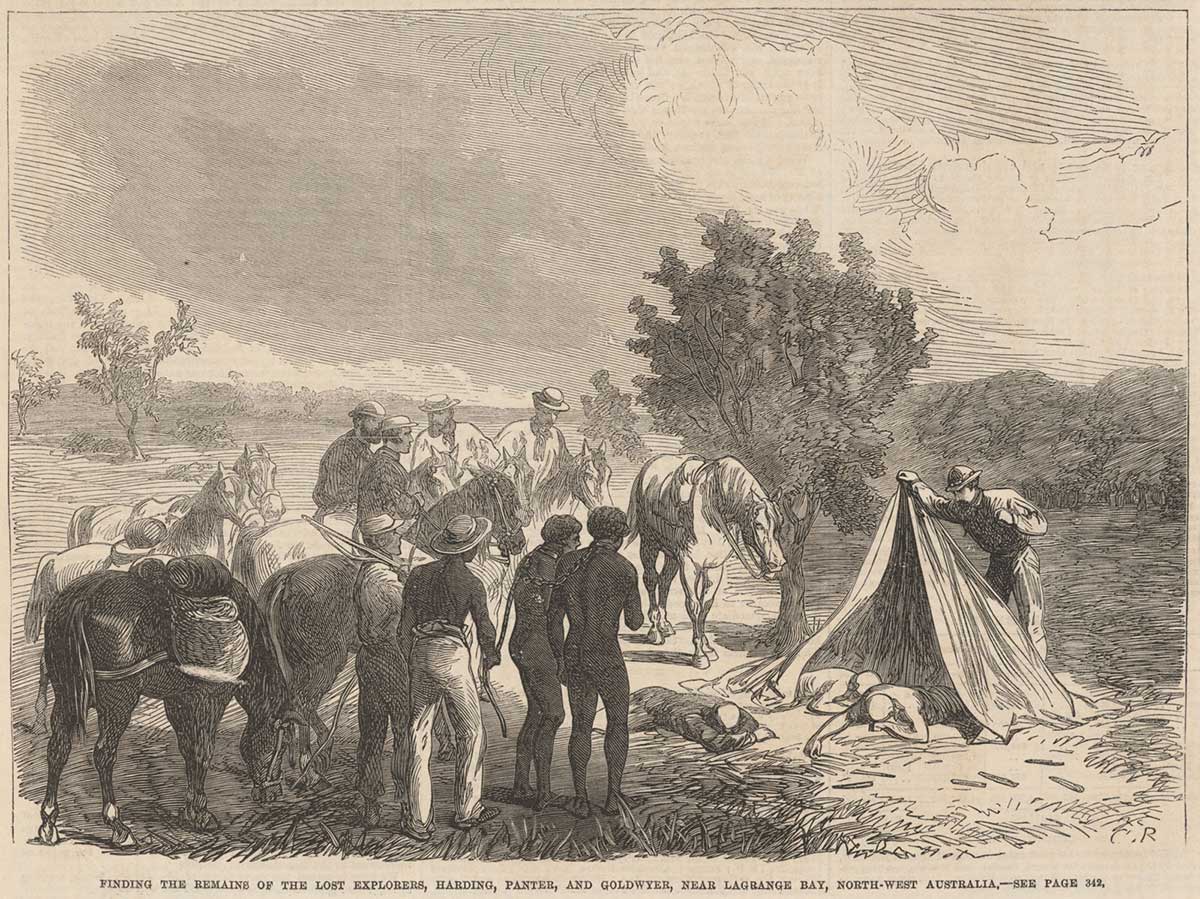

4th April 1865: With what dreadful anxiety we rode up to that tree; our feelings upon reaching it are beyond expression; there, at its foot, lay the dead bodies of our friends where they had been murdered while sleeping months before . . . Scattered round were broken pieces and splinters of spears and [clubs], three journal books, leather pack bags, pouches, powder flasks, rusted revolvers, rugs, boots, and usual traveling equipments. We sat for a few minutes on our horses looking sadly down nothing was spoken or heard but the oft-repeated “poor fellows, poor fellows,” in a tone which shewed how much everyone felt...

Maitland Brown, Journal of an Expedition in the Roebuck Bay District, Perth, 1865 p. 7

Evidence A8

‘Murdered in their sleep’

Evidence notes A

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| The plaque has been commissioned by: | Descendants of the three explorers killed in 1864. |

| 1. The people to be commemorated are: | |

| 2. Why they were in the area: | |

| 3. Where they were killed: | |

| 4. When they were killed: | |

| 5. Who killed them: | |

| 6. Why they were killed: | |

| 7. Their significance in history is: |

Memorial plaque A

Evidence package B

Your task:

- Study everything in Evidence set B, making notes as you go

- Look at the questions in Evidence notes B

- Use your notes to create Memorial plaque B

Evidence set B

| B1 Background information |

B2 Location of Roebuck Bay |

B3 Some information about the Aboriginal people of the area |

B4 Journal of FK Panter |

B5 Witness Peir ding marra |

| B6 From the journal of Maitland Brown |

B7 From the journal of Maitland Brown |

B8 From the journal of David Francisco |

B9 From the journal of Maitland Brown |

Evidence B1

Background information

By 1864:

-

Aboriginal people had lived in and around the Roebuck Bay area of Western Australia, near modern-day Broome, for thousands of years.

-

European pastoralists wanted to move into these areas with their animals.

-

Explorers had been in the area previously to find good pastoral land.

-

Explorers had clashed with Aboriginal people before the 1864 expedition in the Broome area.

-

The 1864 expedition, including Panter, was searching for good pastoral land.

-

The 1864 group clashed with Aboriginal people during their search.

-

The three explorers were killed.

-

Four months later a new expedition, led by Maitland Brown, came to the area to find out what had happened to the missing explorers.

-

There were clashes with Aboriginal people during and after the search and many Aboriginal people were killed.

Evidence B2

Location of Roebuck Bay

Evidence B3

Some information about the Aboriginal people of the area

-

The area is the traditional land of the Karajarri group.

-

Their land is the desert region between Roebuck Bay and Eighty Mile Beach.

-

They lived a nomadic life in family groups, relocating periodically to take advantage of different resources available in various places at different times of the year.

-

Fresh water is rare in the area, and wells are a vital resource.

-

There are areas of special ceremonial or spiritual significance that only fully initiated tribal members can visit.

Horton, David (ed) 1994, The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia, AIATSIS, Canberra, vol. 1 p. 534

Evidence B4

Journal of FK Panter

November 12th 1864: Started at daylight across the plains for 6 miles, all of which was well grassed with 5 kinds; came to a [place] with water 10 inches from the surface and, I have no doubt, in some places on it; trees 50 – 60 feet high almost perfectly straight; at 3 miles farther came to a small lake (5 acres) with beautiful fresh water, thousands of cockatoos, ducks, & c., shot four. In the afternoon Mr. Harding and myself found more swamps at 3 miles distant in a S.E direction, there was not much water in them but splendid grass all round; we also found several strong springs...; kangaroo tracks very numerous; returned to camp before sunset; saw 12 flamingoes.

Nov. 13: Remained in camp. Early in the morning – natives came to us; gave them 5 cockatoos and 5 pigeons; they left soon after but in an hour returned with spears, &c., and as they appeared to be up to some mischief we frightened them away by firing a revolver; they kept whispering and making signs we could not understand. In another hour we again saw them sneaking behind some bushes, but when seen they ran away.

Perth Gazette and WA Times, 12 May 1865

Evidence B5

Witness Peir ding marra

11 March 1865: A native named Peir ding marra came a few days from the east, and told me that about four months ago three white men with four horses were seen one night about ten days journey to the eastward of this, by the Wiogararry tribe of natives, at a river called Boolu Boolu; the white men slept there that night and next morning proceeded in this direction, but during the day were met and attacked by the natives who saw them the night before with others but the white men immediately shot and killed three of their number which caused the rest to run away; the white men did not come any further this way but returned that day to their camp of the night before, which was on a level plain near the bank of the river; to this place the natives followed them keeping out of sight, and then watched them until all fell asleep when with increased numbers stole upon them, stuck spears thro them all and tried to keep them pinned to the ground, but without success as they got on their feet in spite of their wounds and all the efforts made to prevent them, and killed fifteen of the natives and succeeded in driving the rest away.

These knowing the white men to be mortally wounded, collected more natives who were all through the night gathering from all quarters, and returned before daylight this time overpowering the white men who were unable to offer much resistance, by rushing upon them with spears and clubsticks.

The next day they killed the horses with clubs. They have not touched an article belonging to the white men.

Maitland Brown to Colonial Secretary De Grey River, 11 March 1865 CSR Acc 36, vol. 555, pp 169-70, Battye Library

Evidence B6

From the journal of Maitland Brown

3rd April 1865: Rested the horses all day; went on board the ‘Clarence Packet’ with Mr.Burgess, Williams, and... two... prisoners... I feel sure they are... guilty, and consequently know where to take us to; kindness shall at first be used to induce them to shew us what we want, if that fails they should be put to tests which shall prove positively their innocence or guilt.

Evidence B7

From the journal of Maitland Brown

I trust that throughout the whole trip there will be no necessity for capture — that not only amongst this lot, but also amongst all others we may meet, the guilty natives, if such there are, will either attack us or resist us in such a manner as will of itself justify us in exterminating them.

Evidence B8

From the journal of David Francisco

Wednesday 5th April 1865: After breakfast returned to Boola Boola to pack up and remove the remains whilst we were all thus engaged the two native prisoners bolted and native Tom started in pursuit. As they entered the thicket Tom fired his revolver at them and as they continued to run, he fired a second shot and they both fell. It was then found that they were both mortally wounded, one dying almost immediately and the second about ten minutes afterwards, acknowledging his guilt with his last breath. Dined off a Kangaroo shot by Dugal, Tom also shot a large bird, very much resembling a Flamingo.

Typescript 919 414 ROE Battye Library

Evidence B9

From the journal of Maitland Brown

[We encountered] 70 natives, men, women and children... In ten minutes those of the natives who were able had gained the mangroves and all was over; six remained upon the plain dead and dying and about 12 others stood little chance of recovery. The only damage to our side, was a serious wound inflicted by a [club] on William's mare's head ... It was evident that this was the first lesson taught the natives in this district, of the superiority of civilised men and weapons over savage and that as is the nature of all savages, they had attributed the kindness and forbearance exercised towards them by Harding and his comrades to fear...

Maitland Brown, Journal of an Expedition in the Roebuck Bay District, Perth, 1865 page 21

Evidence notes B

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| The plaque has been commissioned by: | Descendants of the Aboriginal people killed in 1864. |

| 1. The people to be commemorated are: | |

| 2. Why they were in the area: | |

| 3. Where they were killed: | |

| 4. When they were killed: | |

| 5. Who killed them: | |

| 6. Why they were killed: | |

| 7. Their significance in history is: |

Memorial plaque B

Bringing the evidence together

1. Compare your notes and memorials for the two different versions of this event. How do you explain the differences between them?

2. Each group has often used the same evidence, but responded to it and interpreted it differently. Explain why this can happen.

This activity has actually been done in real life for these events. Here is a memorial in a park in Fremantle, Western Australia, to the memory of the three explorers and the group that was sent to discover their fate — especially Maitland Brown, whose bust is on top of the memorial.

There are two plaques on the memorial. The first plaque was created in 1913. The second plaque was created in 1994. Below are photographs of the two plaques with transcriptions of the words.

1913 PLAQUE

THIS MONUMENT WAS ERECTED BY CJ BROCKMAN AS A FELLOW BUSH WANDERER'S TRIBUTE TO THE MEMORIES OF PANTER, HARDING AND GOLDWYER.

EARLIEST EXPLORERS AFTER GREY AND GREGORY OF THIS TERRA INCOGNITA. ATTACKED AT NIGHT BY TREACHEROUS NATIVES THEY WERE MURDERED AT BOOLA BOOLA NEAR LA GRANGE BAY ON THE 13 NOVEMBER 1864.

ALSO AS AN APPRECIATIVE TOKEN OF REMEMBRANCE OF MAITLAND BROWN ONE OF THE PIONEER PASTORALISTS AND PREMIER POLITICIANS OF THIS STATE. INTREPID LEADER OF THE GOVERNMENT SEARCH AND PUNITIVE PARTY. HIS REMAINS TOGETHER WITH THE SAD RELICS OF THE ILL FATED THREE RECOVERED WITH GREAT RISK AND DANGER FROM LONE WILDS REPOSE UNDER A PUBLIC MONUMENT IN THE EAST PERTH CEMETERY.

LEST WE FORGET.

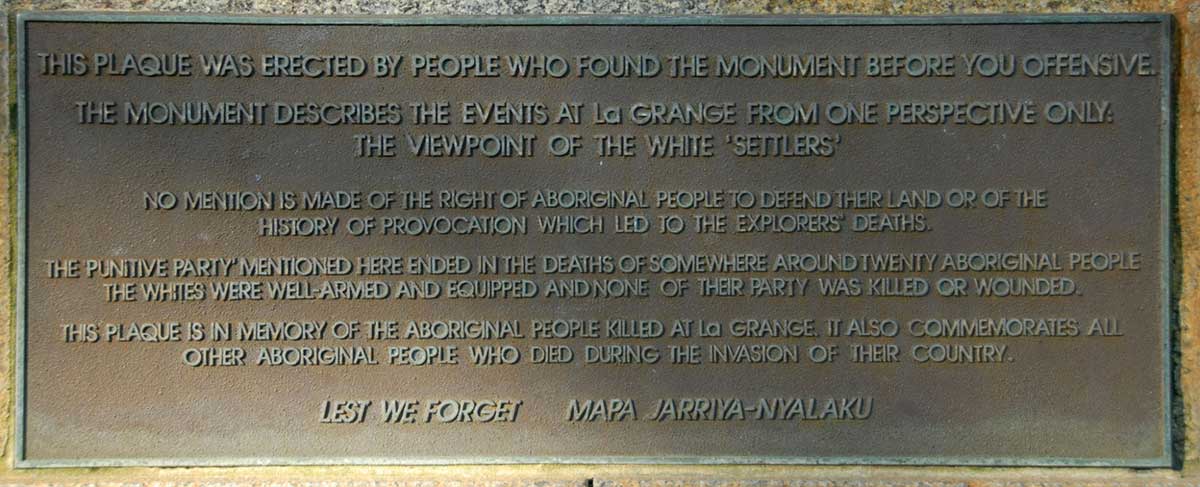

1994 PLAQUE

THIS PLAQUE WAS ERECTED BY PEOPLE WHO FOUND THE MONUMENT BEFORE YOU OFFENSIVE. THE MONUMENT DESCRIBES THE EVENTS AT LA GRANGE FROM ONE PERSPECTIVE ONLY; THE VIEWPOINT OF THE WHITE 'SETTLERS'. NO MENTION IS MADE OF THE RIGHT OF ABORIGINAL PEOPLE TO DEFEND THEIR LAND OR OF THE HISTORY OF PROVOCATION WHICH LED TO THE EXPLORERS' DEATHS. THE 'PUNITIVE PARTY' MENTIONED HERE ENDED IN THE DEATHS OF SOMEWHERE AROUND TWENTY ABORIGINAL PEOPLE. THE WHITES WERE WELL-ARMED AND EQUIPPED AND NONE OF THEIR PARTY WAS KILLED OR WOUNDED.

THIS PLAQUE IS IN MEMORY OF THE ABORIGINAL PEOPLE KILLED AT LA GRANGE. IT ALSO COMMEMORATES ALL OTHER ABORIGINAL PEOPLE WHO DIED DURING THE INVASION OF THEIR COUNTRY.

LEST WE FORGET.

MAPAJARRIYA-NYALAKU

3. List some of the emotive words used in each plaque.

4. How are these emotive words meant to influence your response to the events described?

5. The final words of each are ‘Lest We Forget’. Where is this phrase usually to be found in Australia? What is it that the different plaques want us to remember?

6. Why do you think only one story was told until 1994?

7. Which version of the memorial better represents the situation as you now understand it? Why?

8. Can you accept all or part of either version of the story? Explain your reasons.

9. Rae Minnicon, an Aboriginal student who worked with the Bidyadanga community on the project for the second plaque, said these words at the unveiling ceremony in 1994:

This particular monument is a window into our past. It is a window into the way in which our country was invaded and the atrocities which have taken place with that invasion. But it is not only a window into our past, it is also a window into our present and if we want to understand the particular situation which we as Aboriginal people and non-Aboriginal people face in this country, then we would do well to look into and explore the windows of the past. Monuments like this are dotted all across the Australian landscape.

Many old memorials have stories or versions of events that would now be considered inaccurate and offensive. What should be done about these memorials as our understanding of those events change? Should they be left as they are, added to or removed altogether? Discuss this and decide what your suggestion would be.

10. If you are able to, look at the memorials in your own or a nearby community. Apply a similar analysis to them, asking such questions as:

- Whose ‘voice’ does it present?

- What is its message for us today?

- Might others have a different interpretation of the story it represents?

- How fair and accurate is it as a representation of the event?