Learning module:

Rights and freedoms Defining Moments, 1945–present

Investigation 1: Exploring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights through key Defining Moments

1.11 1968 Equal wages decision

It is 1968.

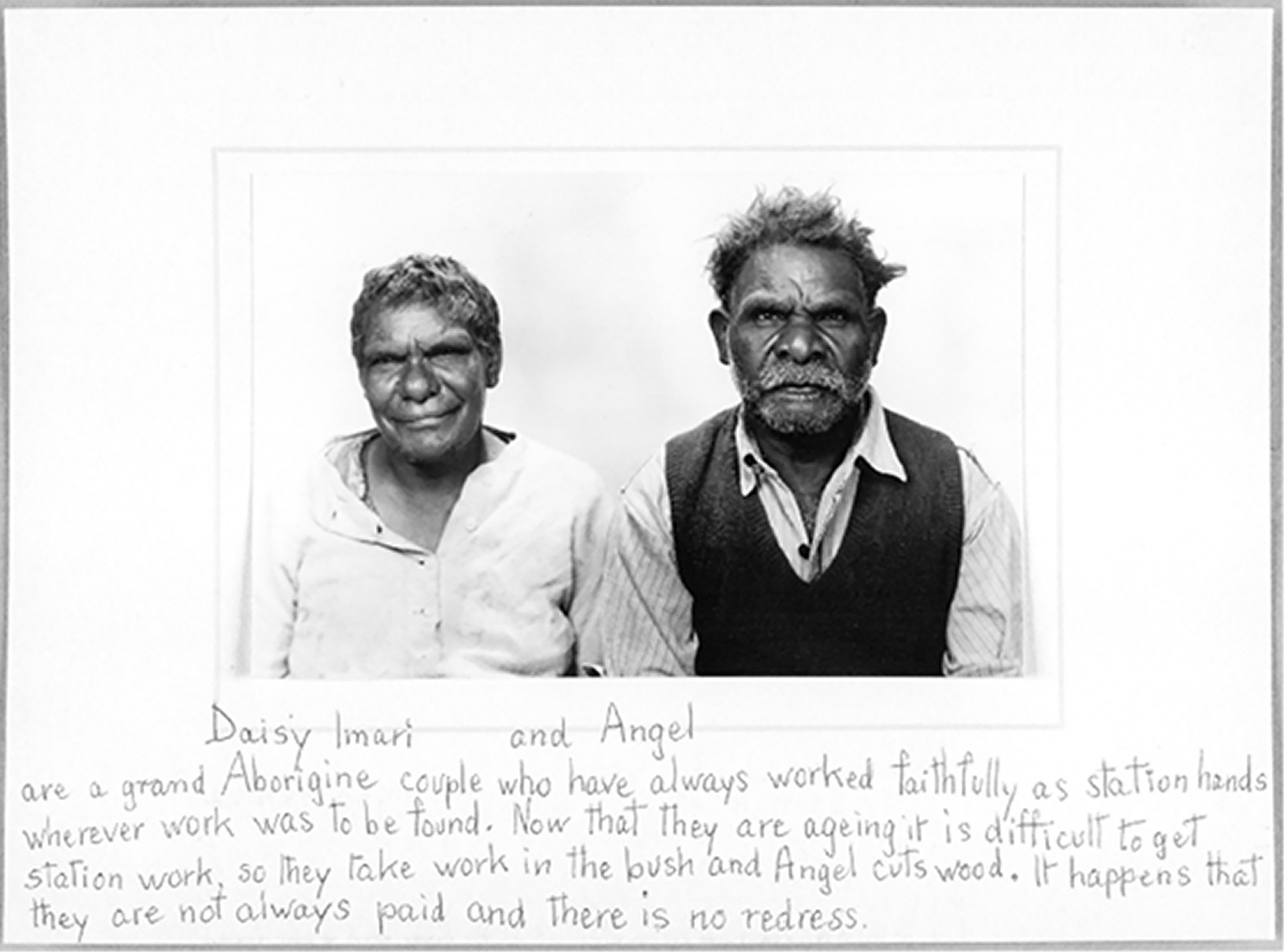

Aboriginal pastoral workers in the Northern Territory are paid far lower wages than non-Indigenous workers, and generally live in terrible conditions. This is an unjust situation.

At the same time, the Aboriginal workers are allowed to live on the properties and their traditional land, maintain many cultural traditions, and have their families with them. They are also allowed time to carry out their cultural obligations. Employers say they pay lower wages because the Aboriginal workers work fewer hours and they are given the benefits of occupation of their traditional lands. If wages are increased, employers will no longer continue these ‘benefits’.

When there is a movement for what seems to be simple justice — the payment of equal wages — the conflict in this situation is exposed. Will equal wages benefit the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, or will it lead to their removal from their traditional lands?

Read the information below from the National Museum of Australia’s ‘Collaborating for Indigenous Rights’ on the 1968 equal wages decision and answer the questions that follow.

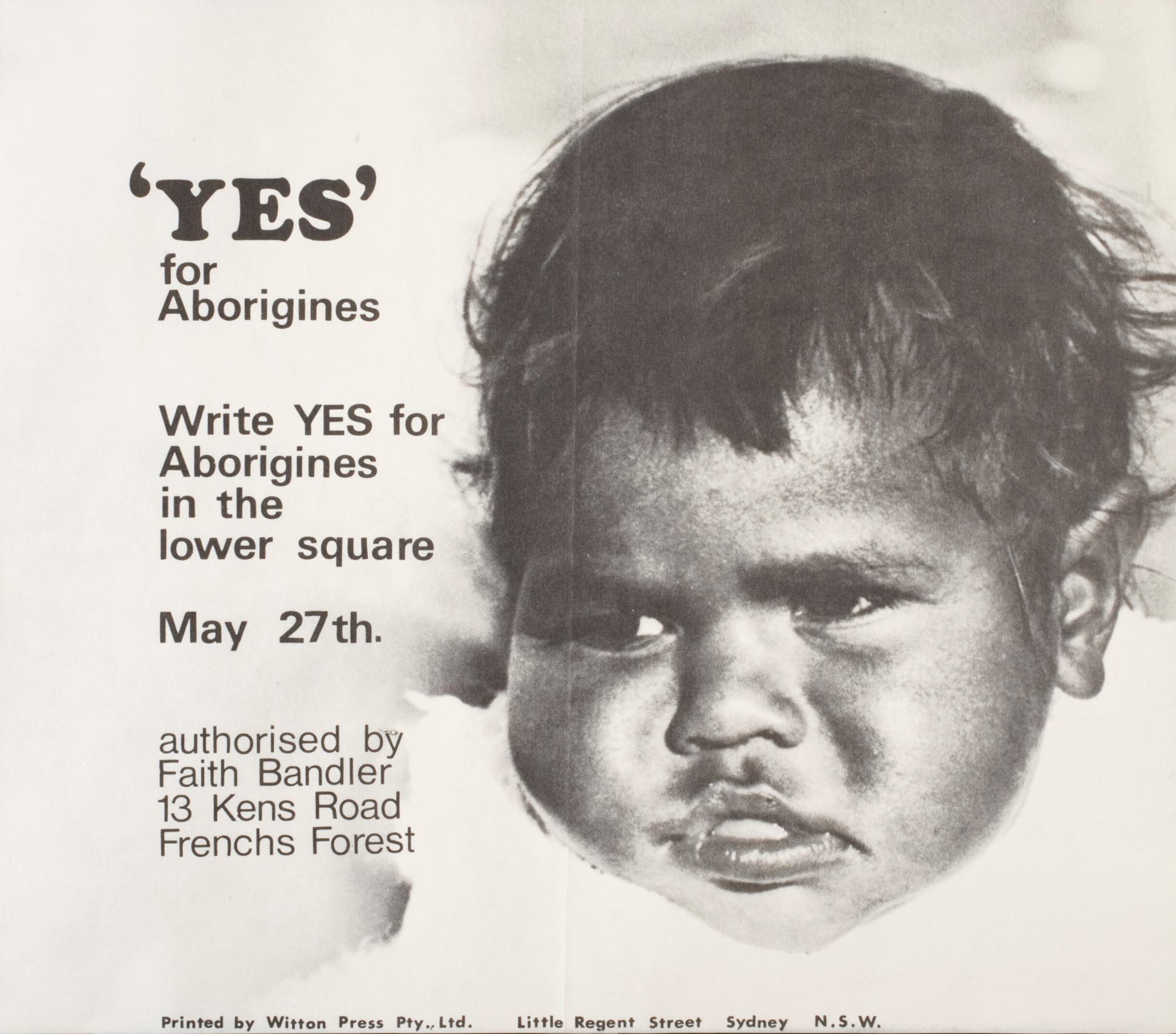

For white civil rights activists in the 1960s, equal pay was the basic marker of acceptance and social inclusion in Australian society ... people who were paid such a small proportion of the basic wage were not able to live like white people. This requirement was part of the government’s assimilation policy, which aimed to ‘absorb’ Aboriginal people into ‘white society’.

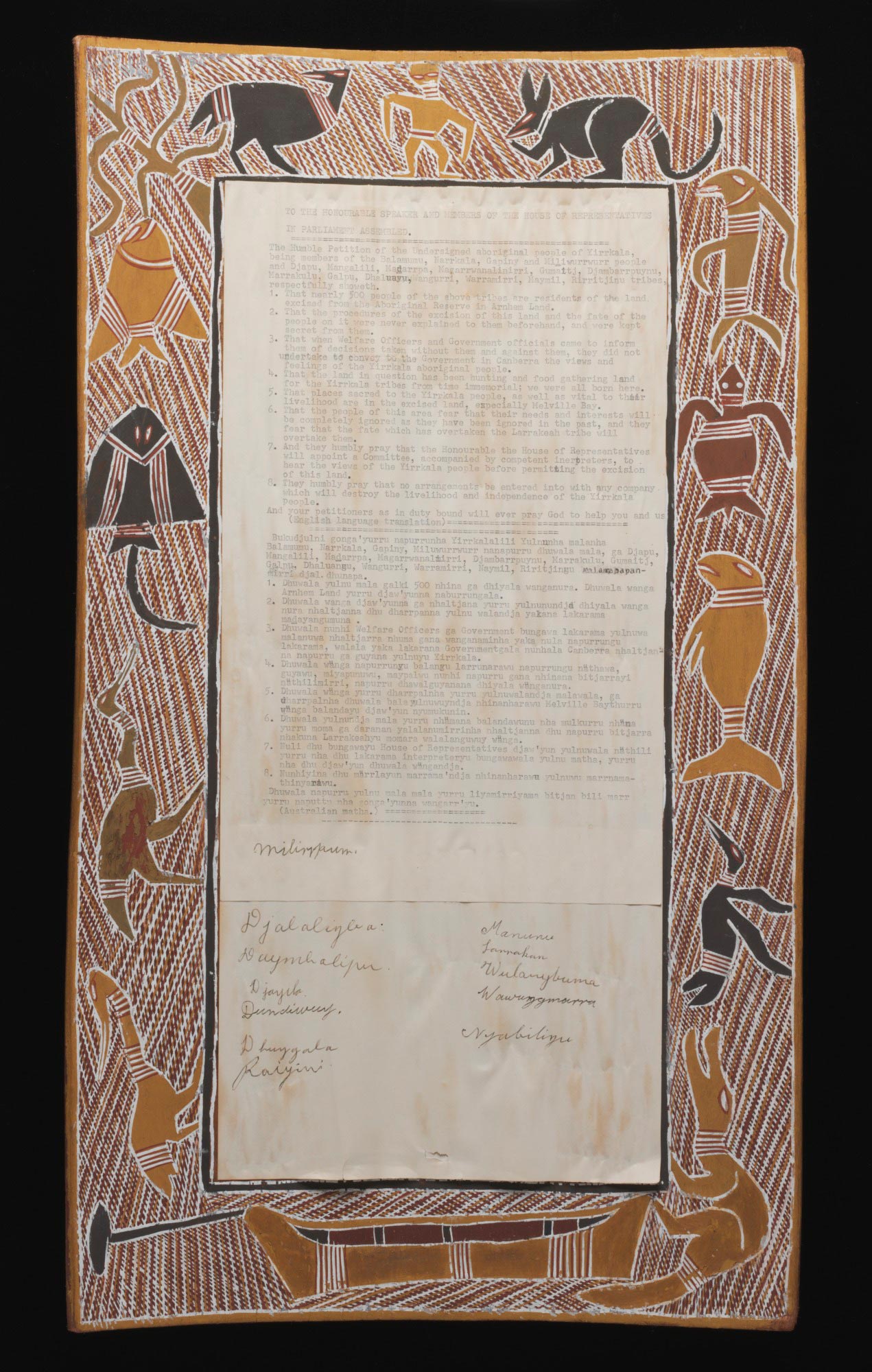

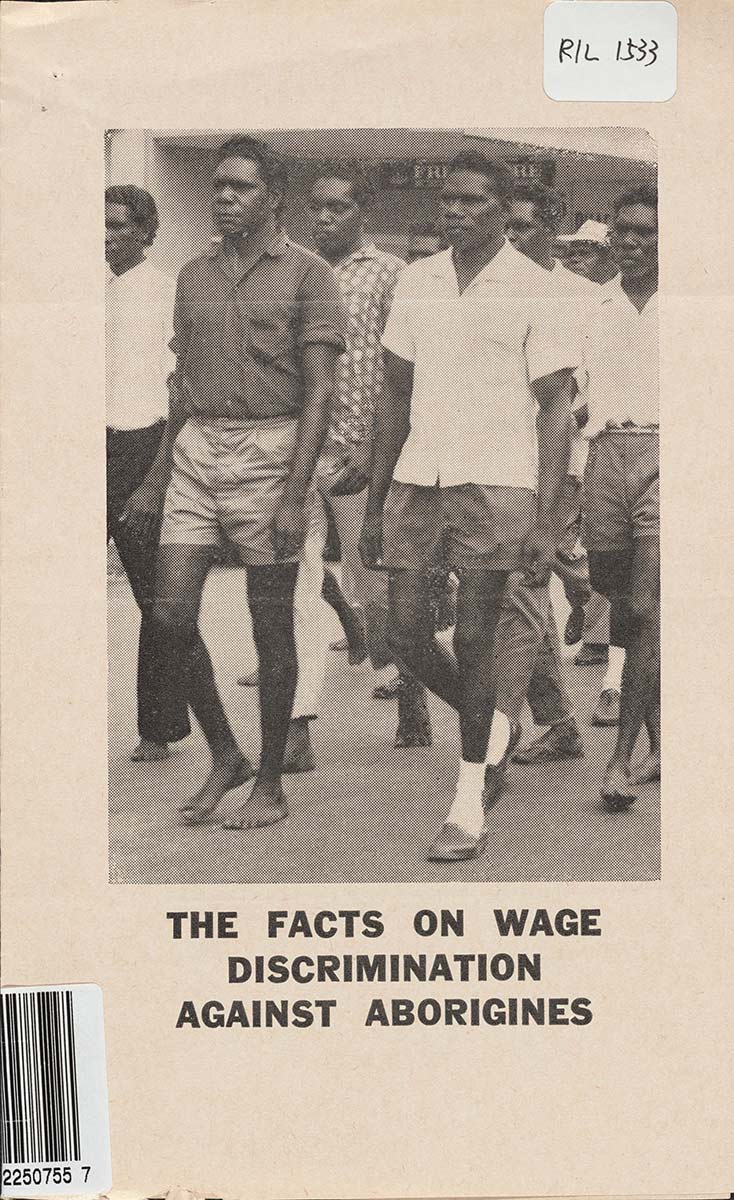

At the 1962 Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement (FCAA) conference, Shirley Andrews gave a powerful address setting out the facts on wage discrimination and arguing that trade unionists had a responsibility to get involved in campaigns to bring Aboriginal workers under the award system, which guaranteed a fair wage. The next year, Andrews and others lobbied Australian Council of Trade Union (ACTU) delegates, and the ACTU put out a policy position announcing ‘there must be an end to wage discrimination’. Union representatives joined the Equal Wages for Aborigines Committee and helped finance a leaflet ‘Equal wages for Aborigines: there must be an end to wage discrimination’. The leaflet urged unionists to protest to the Minister for Territories about the low wages for Aboriginal pastoral workers in the Northern Territory.

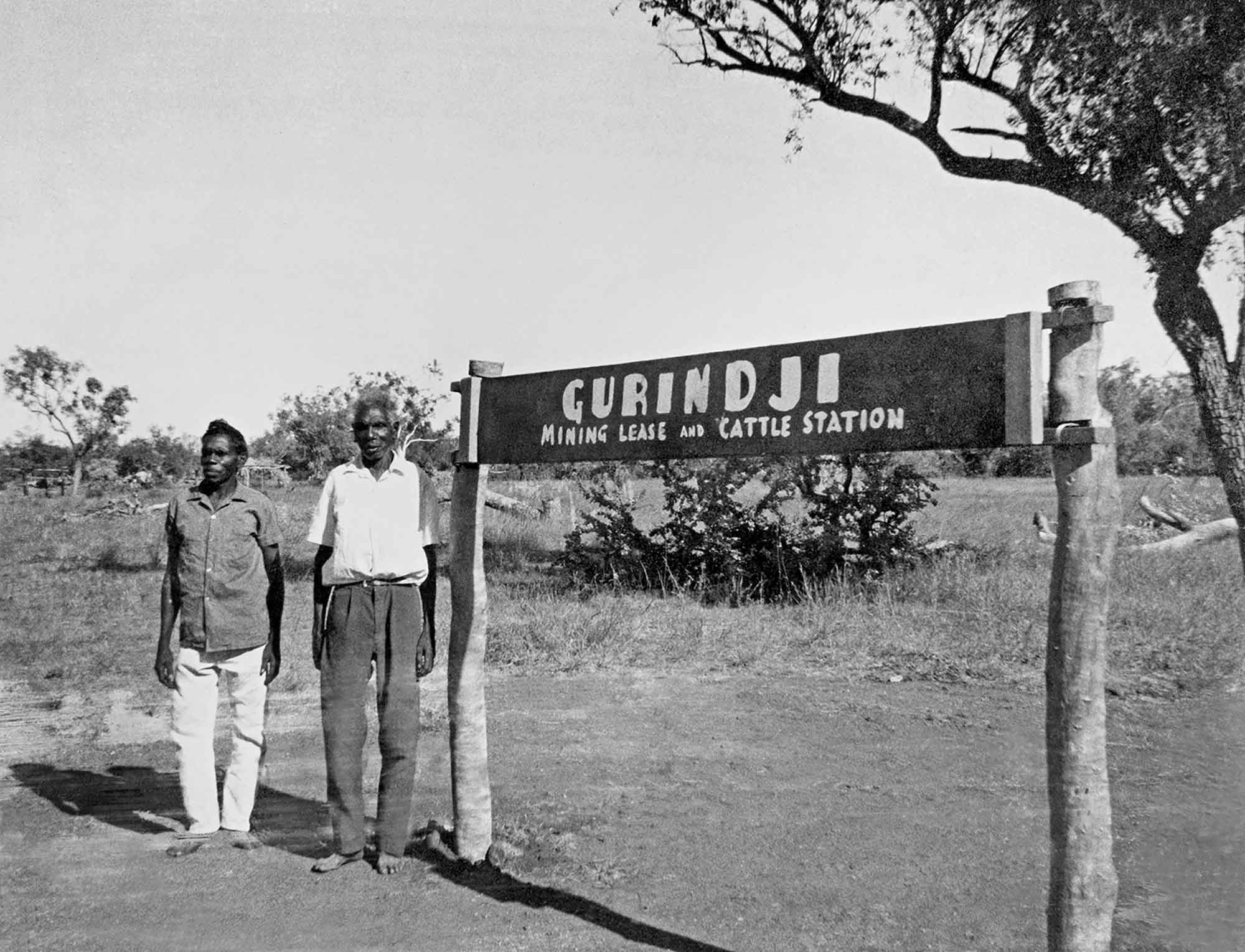

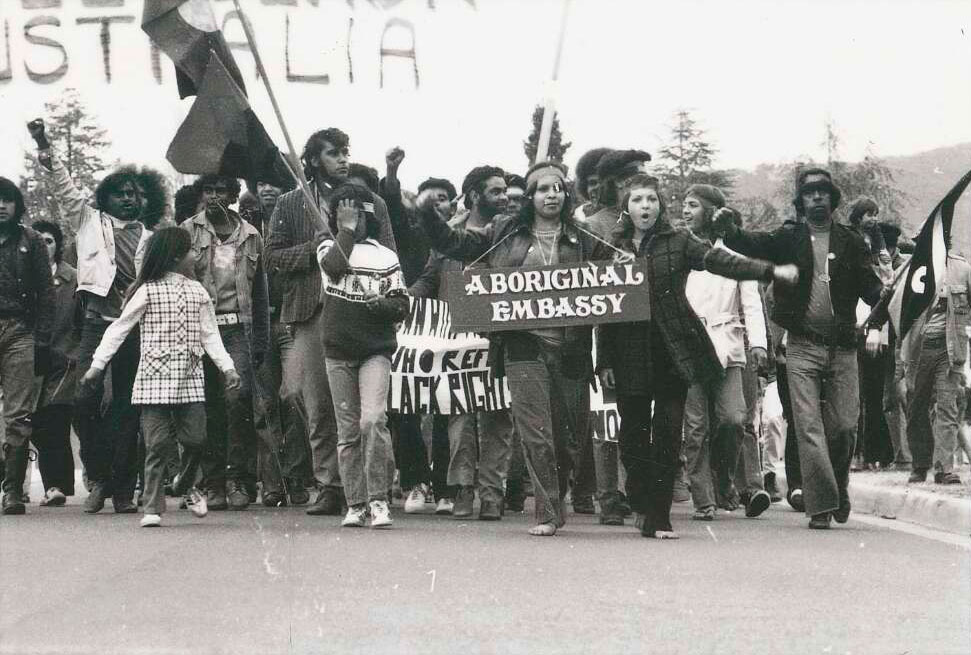

Aboriginal workers had concerns other than wages. For example the Gurindji pastoral workers were unhappy about their appalling living conditions. They had to live on a poor diet that consisted of salt beef, damper, sugar and tea. There were also regular incidents of white stockmen coming back into camp, when the Aboriginal stockmen were still out with the cattle, to sexually assault Aboriginal women.

In 1964 the North Australian Workers Union presented a case for equal wages for Aboriginal pastoral workers. The cattle industry, the largest employer of Aboriginal labour, was not legally required to pay Northern Territory Aboriginal drovers more than £3. 3s. 3d perweek. White drovers got five times this amount. The North Australian Workers Union case before the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission would, if successful, end this discrimination.

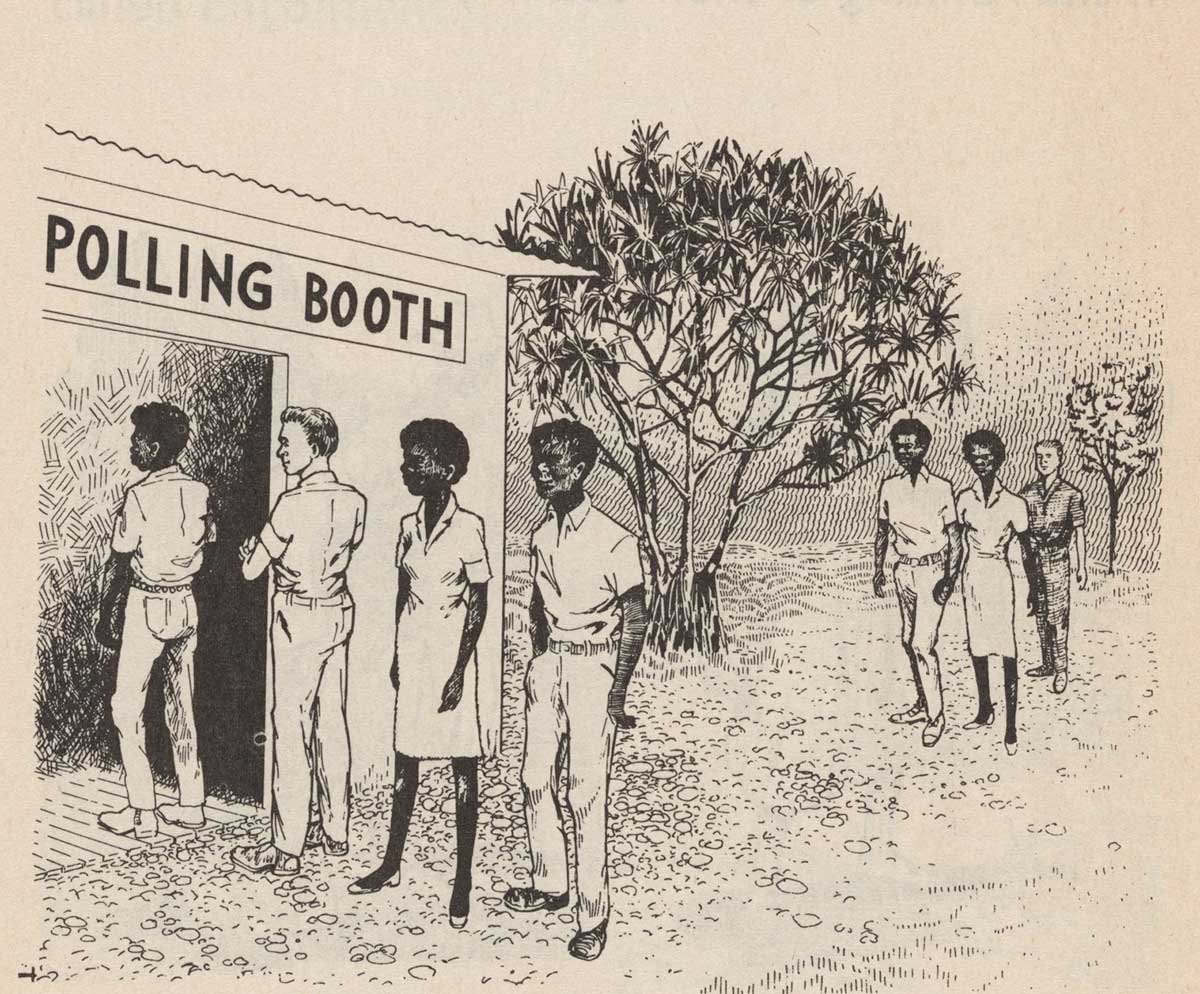

Two years earlier the Electoral Act had extended voting rights to Aboriginal people, but industrially they were still outside the award structure which guaranteed fair wages to workers. The Australian industrial system, built up over more than half a century, also laid down working conditions, annual and sick leave and workers’ compensation. Aboriginal workers, however, were specifically excluded from awards in jobs where they were most represented, such as in the pastoral industry.

In March 1966 the Commission made its long-awaited decision on the proposed variations to the Cattle Station Industry (Northern Territory) Award 1951. It agreed to the deletion of the clauses which excluded Aboriginal pastoral workers from the award but delayed the date when it would put into practice to 1 December 1968. The Commission’s judgment explained that this was to give Aboriginal workers and the Australian Government ‘time to prepare’ for the change. It added, ominously, that it was also necessary ‘to give the pastoralists an opportunity to consider the future of their Aboriginal employees and to make arrangements for their replacement by white labour if necessary’ ... This did happen and many Aboriginal stockmen faced unemployment for the first time.

Reflecting later on the wages campaign, however, Shirley Andrews thought that some critical factors had been missed:

‘One of the mistakes, you know I always feel bad about, was feeling that you had to get equal rights and that wasn’t what was wanted. Because I always felt on the question of wages, you see, that we made a mistake pressing just for equal pay on the cattle stations because we should have realised that what was needed was something different where the Aboriginal people, a whole group of them, you know were paid en masse or something and then they decided what was to be done with the money. Because what happened was that they [the pastoralists] got rid of everyone except their very skilled workers, when they were required to pay better pay but it was always very bad to see that situation where this great big industry with people like Lord Vestey making a fortune and paying twenty pounds income tax or something you know it was all done with Aboriginal labour and skilled labour and dangerous jobs you know, so that always seemed a real sort of sore on the face of the continent more or less that something should be done about. But unfortunately, also as we got better pay, or the unions got the better pay, the cattle industry just happened to strike a downturn as well so it was a disaster in a lot of ways. You know, you can sometimes think you’re doing the right thing and you don’t understand all the factors being so much more complicated particularly for city slickers you know.’

The achievement of equal wages in the pastoral industry thus turned out, for many, to be a hollow victory. Families and whole communities were turned off properties where they had worked for generations. People drifted into towns and were given ‘sit down’ money (unemployment benefits). They were no longer able to fulfil obligations to their country.

Edited from National Museum of Australia, Equal wages, 1963–66, https://indigenousrights.net.au/civil_rights/equal_wages,_1963-66, viewed 14 October 2020; National Museum of Australia, Shirley Andrews, https://indigenousrights.net.au/people/pagination/shirley_andrews, viewed 14 October 2020

1. How did the wage system discriminate against Aboriginal workers in the Northern Territory pastoral industry?

2. How did station owners justify this?

3. Who opposed the injustice?

4. What decision did the court reach on equal payment?

5. What consequences did this have for the Aboriginal workers and their families?

6. How did the decision affect the Aboriginal people’s relationship with their land?

7. What was the significance of the equal wages decision for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights?

8. How would this event have influenced the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights over time?