Learning module:

Rights and freedoms Defining Moments, 1945–present

Investigation 1: Exploring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights through key Defining Moments

1.20 1993 Native Title Act

It is 1993.

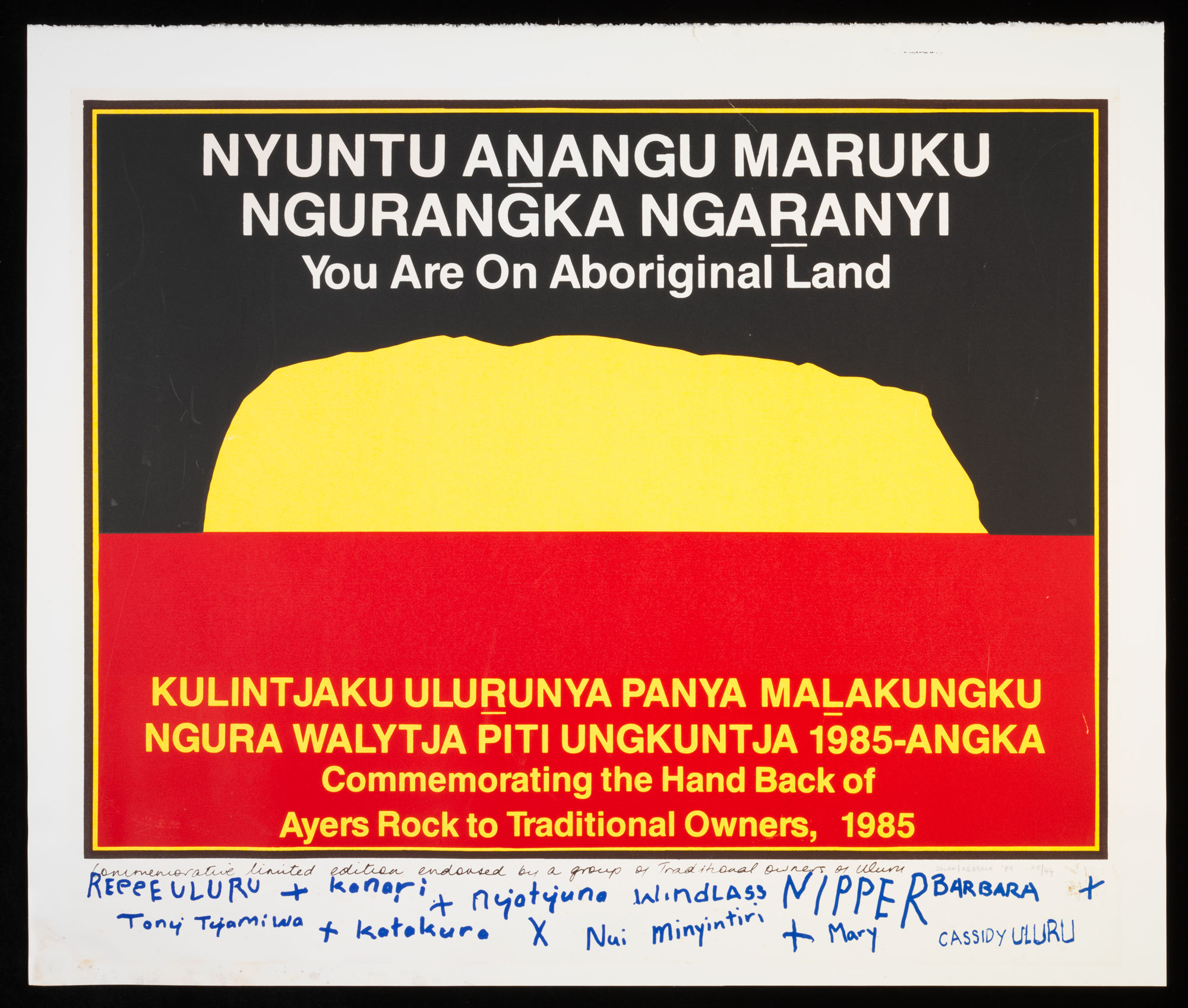

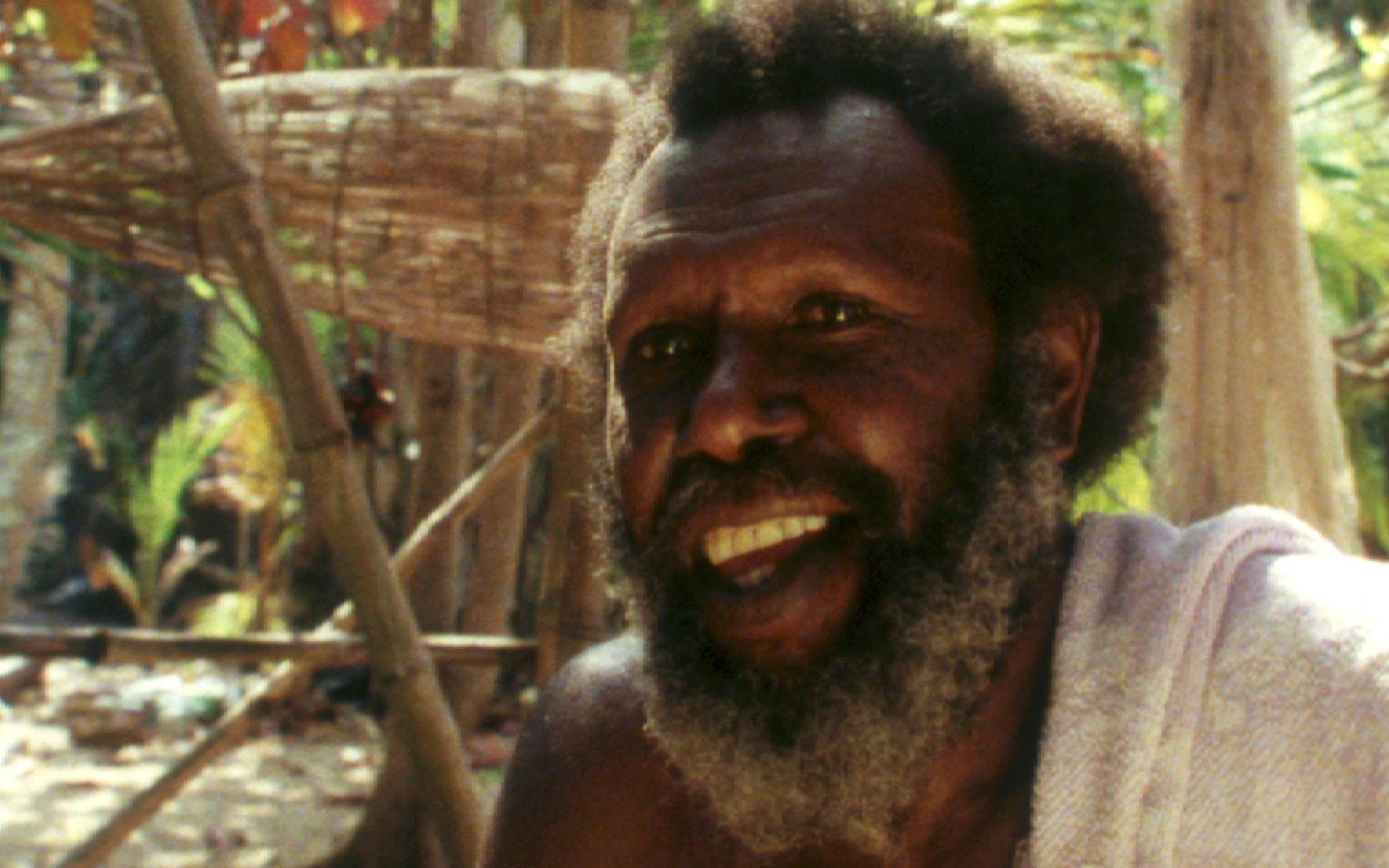

In the previous year a High Court decision challenged the legal basis on which much of the land of Australia was held. The case found that there could be circumstances in which the traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander owners still had legal title to their land.

How would the Australian Parliament deal with this matter, and create legal certainty over Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land ownership throughout Australia?

Read the information below on the 1993 Native Title Act, and answer the questions that follow.

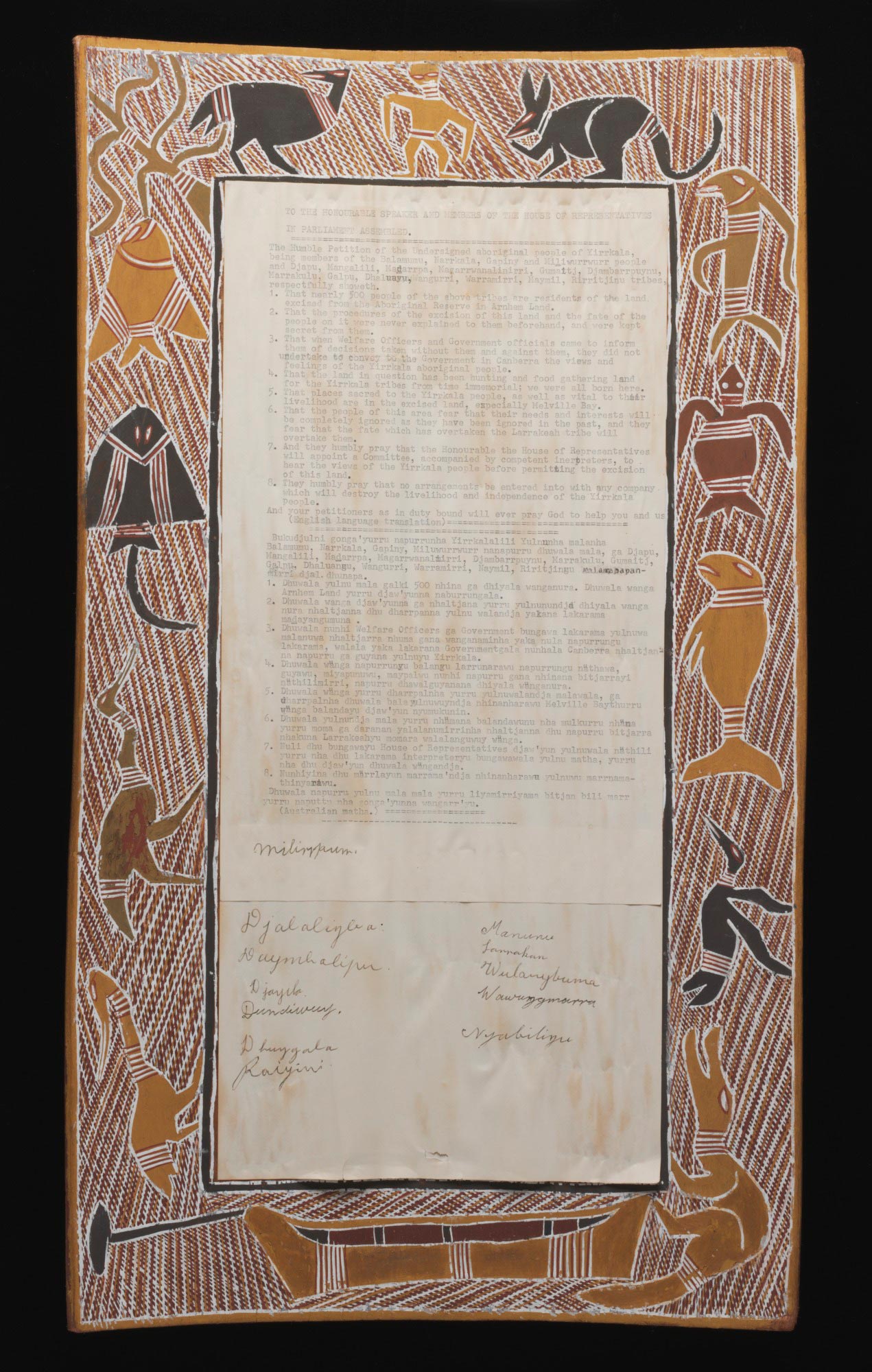

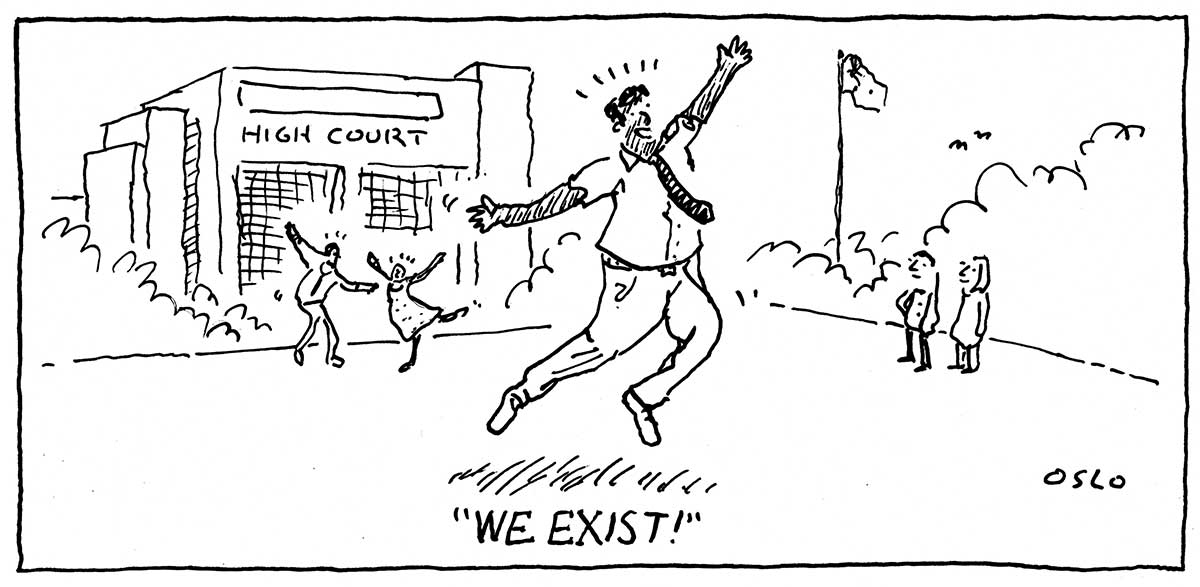

The 1993 Commonwealth Native Title Act was passed by the Australian Parliament in response to the 1992 High Court Mabo decision.

That decision had created the legal concept of native title in that case, but the decision applied only to that case. Aware that the further native title claims would likely occur in court cases using the Mabo decision as a precedent, the Australian government created its native title bill to try to address this issue. The resultant Act ensured that the legal principle of native title would apply to all other situations where that principle applied.

The Act received both support and opposition. Supporters saw it as the appropriate way of implementing the principle of native title in the most efficient and effective way; opponents saw it as possibly threatening to take potentially productive land away from economic development. Many of the opponents did not realise that native title could not be claimed where the land has been previously legally alienated, or legally sold; so there was never a threat to people’s homes and land. The land involved was land that was still owned by the Crown (the government) and leased out, not sold.

The Act set up a tribunal for claimants to apply for native title. Where the tribunal was satisfied that there was a continuing association with land that had not been legally granted to other people, then the claim would be granted. The land would then legally belong to the group of traditional landowners, and give them the right to make decisions about how they wanted their land to be used — for example, for mining. They would share in the benefits of that use through, in such a case, royalty payments by the miners to the traditional landowners.

Native title tribunals were set up in all states. In many cases the process of establishing proof of native title has been long and difficult, partly by the need to provide proof of traditional occupation, partly through the complications of overlapping traditional owner claims, and partly because of the devastation to cultural integrity as a result of colonial settlement.

About 37 per cent of the land mass of Australia is now held under native title, with more claims still to be resolved.

Edited from Australian Law Reform Commission, Review of the Native Title Act 1993, https://www.alrc.gov.au/publications/review-native-title-act-1993-cth, viewed 14 October 2020

1. What is ‘native title’?

2. How was it established?

3. What did this Act do with the legal principle established in the Mabo case?

4. Why was this legislation needed?

5. Why was there both support for and opposition to the legislation?

6. What did native title involve?

7. What was the effect or impact of this Act?

8. What was the significance of the Native Title Act for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights?

9. How would this event have influenced the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights over time?