Learning module:

Rights and freedoms Defining Moments, 1945–present

Investigation 1: Exploring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights through key Defining Moments

1.8 1965 Freedom Ride

It is 1965.

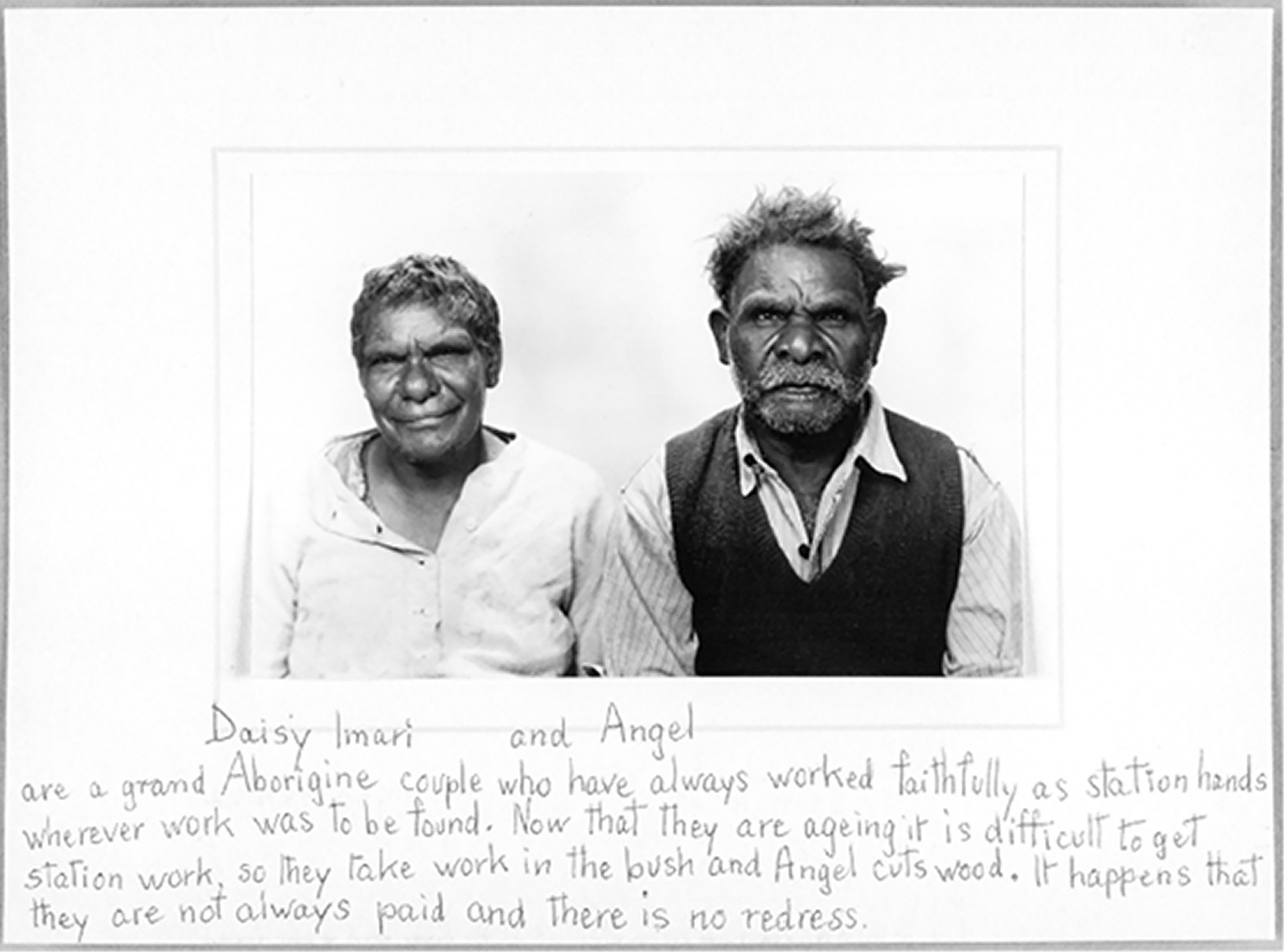

It is a period of increasing awareness of the terrible conditions in which many Aboriginal people live, especially around the edges of country towns, and the discrimination that these people suffer.

Globally it is a time of great social and political change, which includes a highly divisive war in Vietnam and increasing protests against systemic racism, particularly in the United States of America.

Would this emergence of the American civil rights movement and civil rights leaders such as Dr Martin Luther King Jr influence Australia and provide a model for improved Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights?

Read the information below on the 1965 Freedom Ride, taken from the National Museum of Australia’s ‘Collaborating for Indigenous Rights’, and answer the questions that follow.

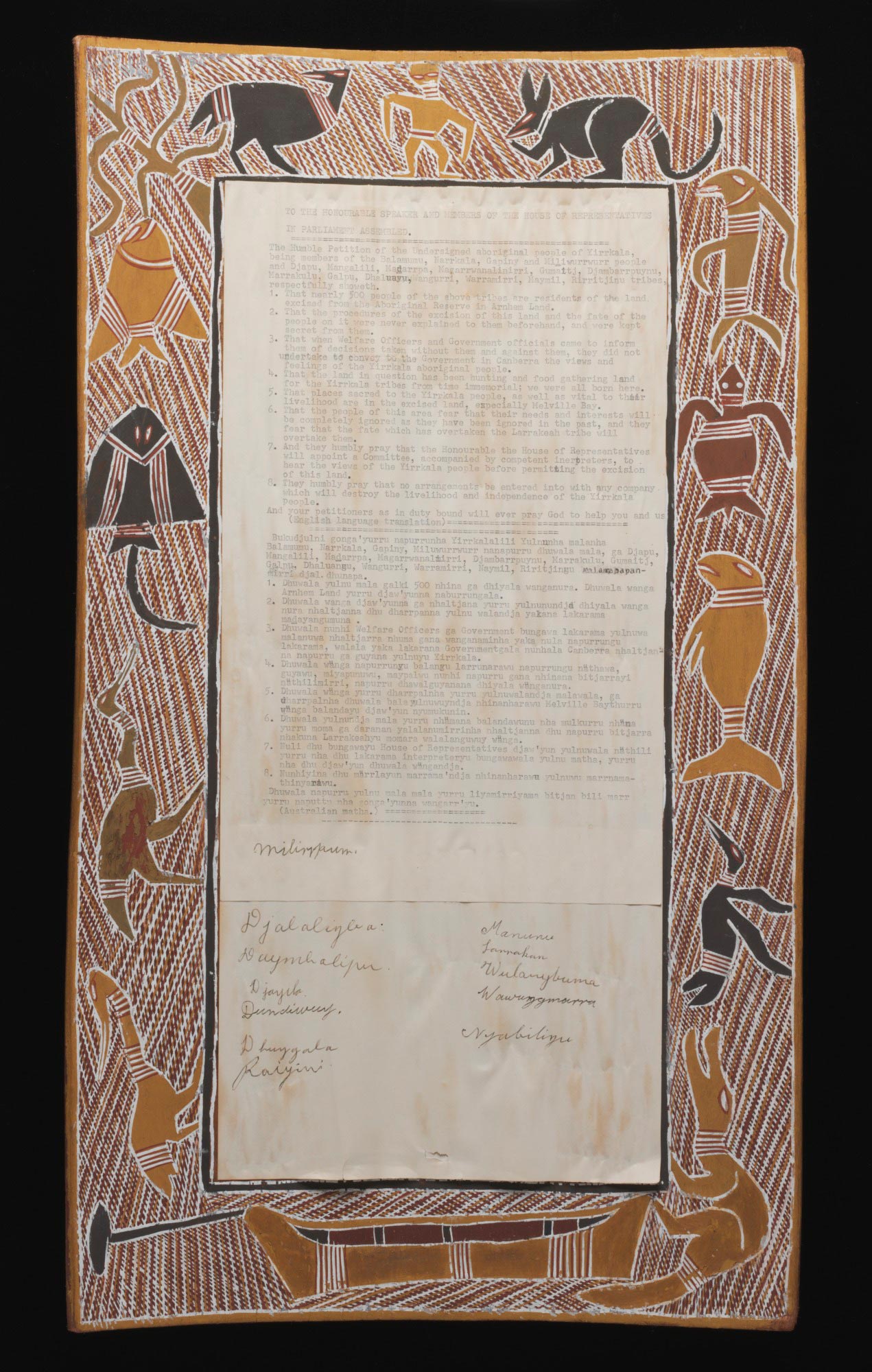

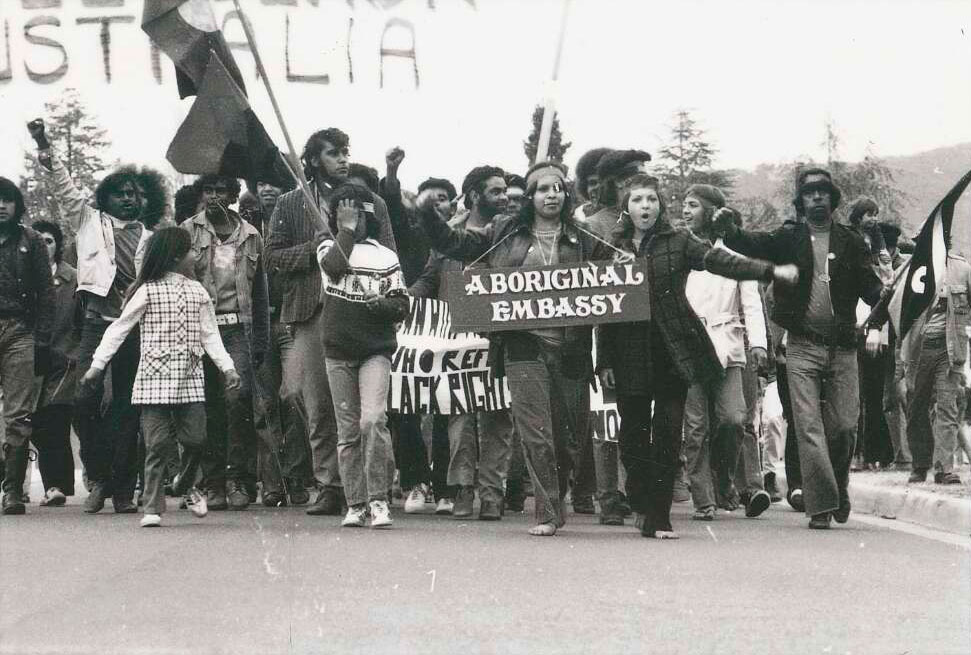

In February 1965 a group of University of Sydney students organised a bus tour of western and coastal New South Wales towns.

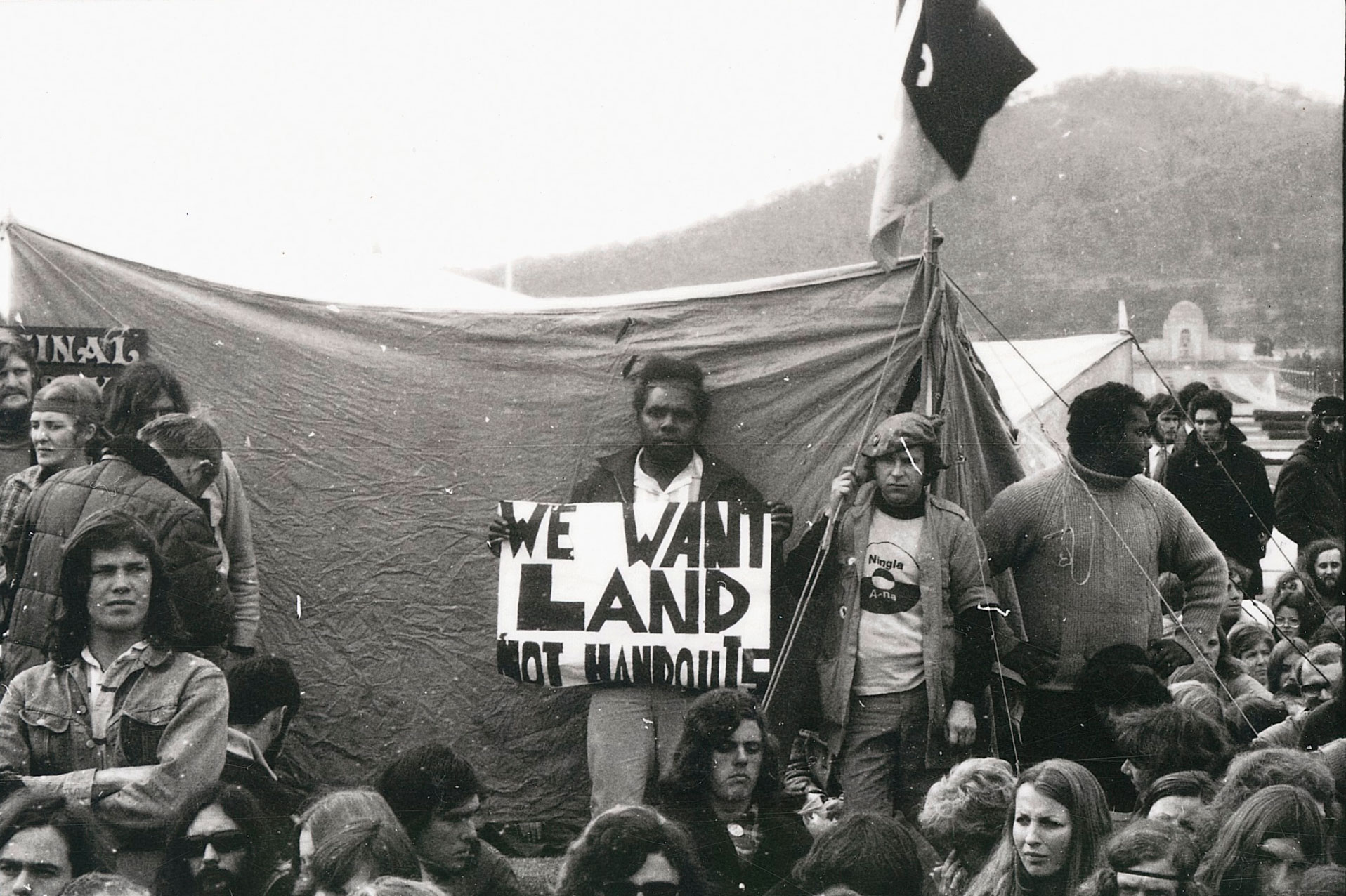

Their purpose was threefold. The students planned to draw public attention to the poor state of Aboriginal health, education and housing. They hoped to point out and help to lessen the socially discriminatory barriers which existed between Aboriginal and white residents. And they also wished to encourage and support Aboriginal people themselves to resist discrimination. The students had formed into a body called Student Action for Aboriginal people (SAFA) in 1964 to plan this trip and ensure media coverage. Charles Perkins, an Arrernte and Kalkadoon man born in Alice Springs, who was a third year arts student at the university, was elected president of SAFA.

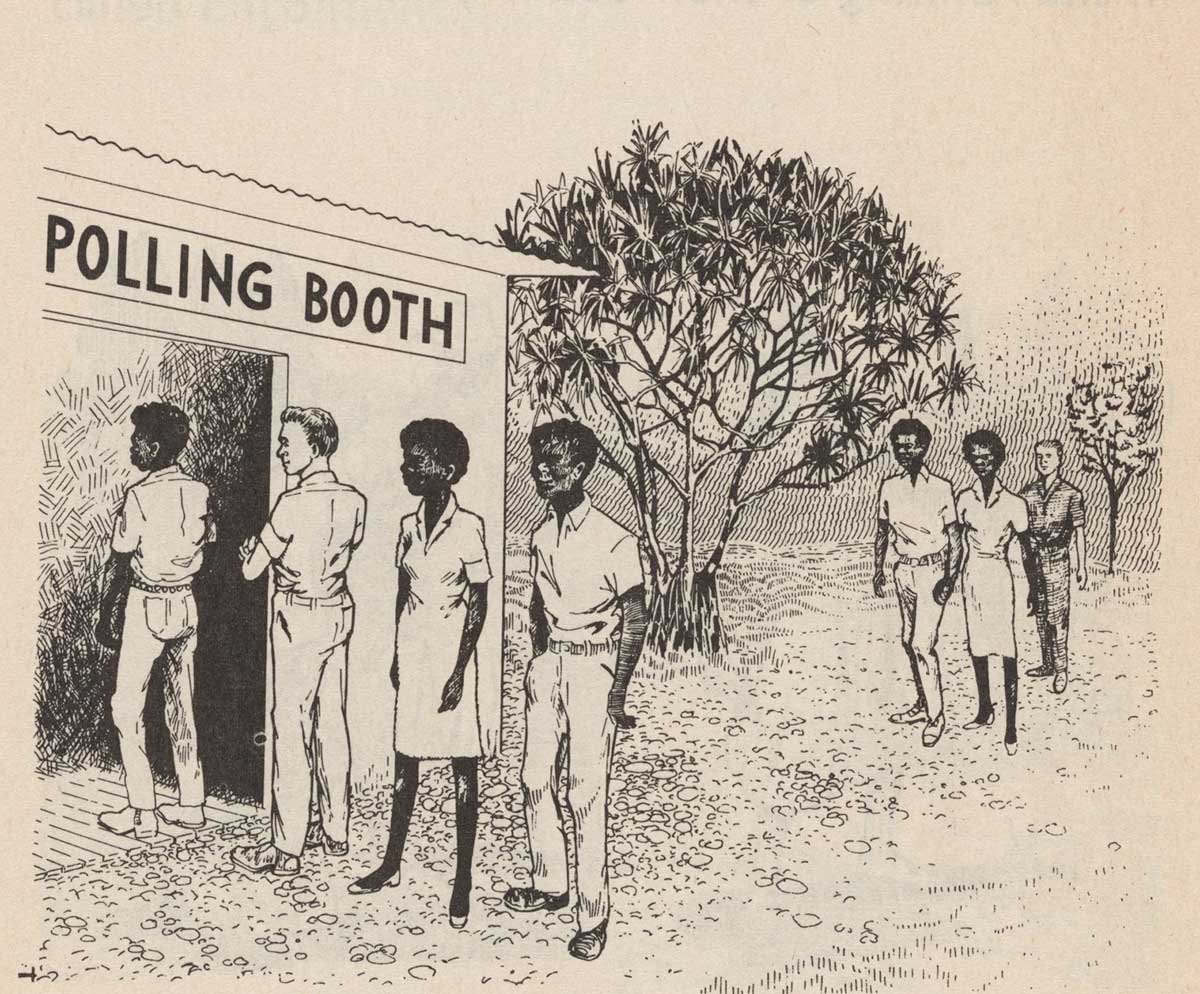

The Freedom Ride, as it came to be called, included visits to Walgett, Gulargambone, Kempsey, Bowraville and Moree (map of the places visited by the Freedom Rides). Students were shocked at the living conditions which Aboriginal people endured outside the towns. In the towns Aboriginal people were routinely barred from clubs, swimming pools and cafes. They were frequently refused service in shops and refused drinks in hotels. The students demonstrated against racial discrimination practised at the Walgett Returned Services League, the Moree Baths, the Kempsey Baths and the Bowraville cinema. They not only challenged these practices, but they ensured that reports of their demonstrations and local townspeople’s hostile responses were available for news broadcasts on radio and television.

Outside Walgett Jim Spigelman trained his home movie camera on the hostile convoy of cars which followed the bus out of town at night and ran it off the road. Darce Cassidy recorded the angry conversations and filed a report to the ABC.

Captured on tape was the vice-president of the Walgett Returned Service League Club who said he would never allow an Aboriginal to become a member. Such evidence was beamed into the living rooms of Australians with the evening news. It exposed an endemic racism. Film footage shocked city viewers, adding to the mounting pressure on the government.

The central role of the film camera in this campaign demonstrated the growing sophistication of activists who recognised the need to show city dwellers what was happening in country towns. The campaigners drew parallels with civil rights movements elsewhere in the world, especially the United States. The news coverage punctured Australian smugness, borne of ignorance, that racism did not exist in Australia.

At Moree (northern New South Wales), which was known to be a town where segregation was practised, the students focused on the swimming pool. The pool became a scene of tension and aggression as they attempted to assist Aboriginal children from the reserve outside town to enter the pool while locals angrily defended the race-based ban.

Charles Perkins reported these events to a crowd of 200 attending the 1965 Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) conference in Canberra. Conference goers heard that one positive result of the students’ activities was that the New South Wales Aborigines Welfare Board publicly announced that it would spend sixty-five thousand pounds on housing in Moree.

The Freedom Ride through New South Wales towns and the publicity it gained raised consciousness of racial discrimination in Australia and strengthened the campaigns to eliminate it which followed.

National Museum of Australia, Freedom Ride, https://indigenousrights.net.au/civil_rights/freedom_ride,_1965, viewed 14 October 2020

1. What was the ‘Freedom Ride’ of 1965?

2. Who was involved in it?

3. What were the aims of the Student Action for Aboriginal people group?

4. What happened during the ride?

5. How were the events during the ride made public?

6. What were the outcomes of the ride?

7. What was the significance of the Freedom Ride for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights?

8. How would this event have influenced the development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights over time?