Learning module:

Second World War Defining Moments, 1939–1945

Investigation 2: The Australian military experience of the war

2.4 What was the soldiers’ experience of the Kokoda Trail?

| WARNING: This page contains some difficult and potentially distressing content |

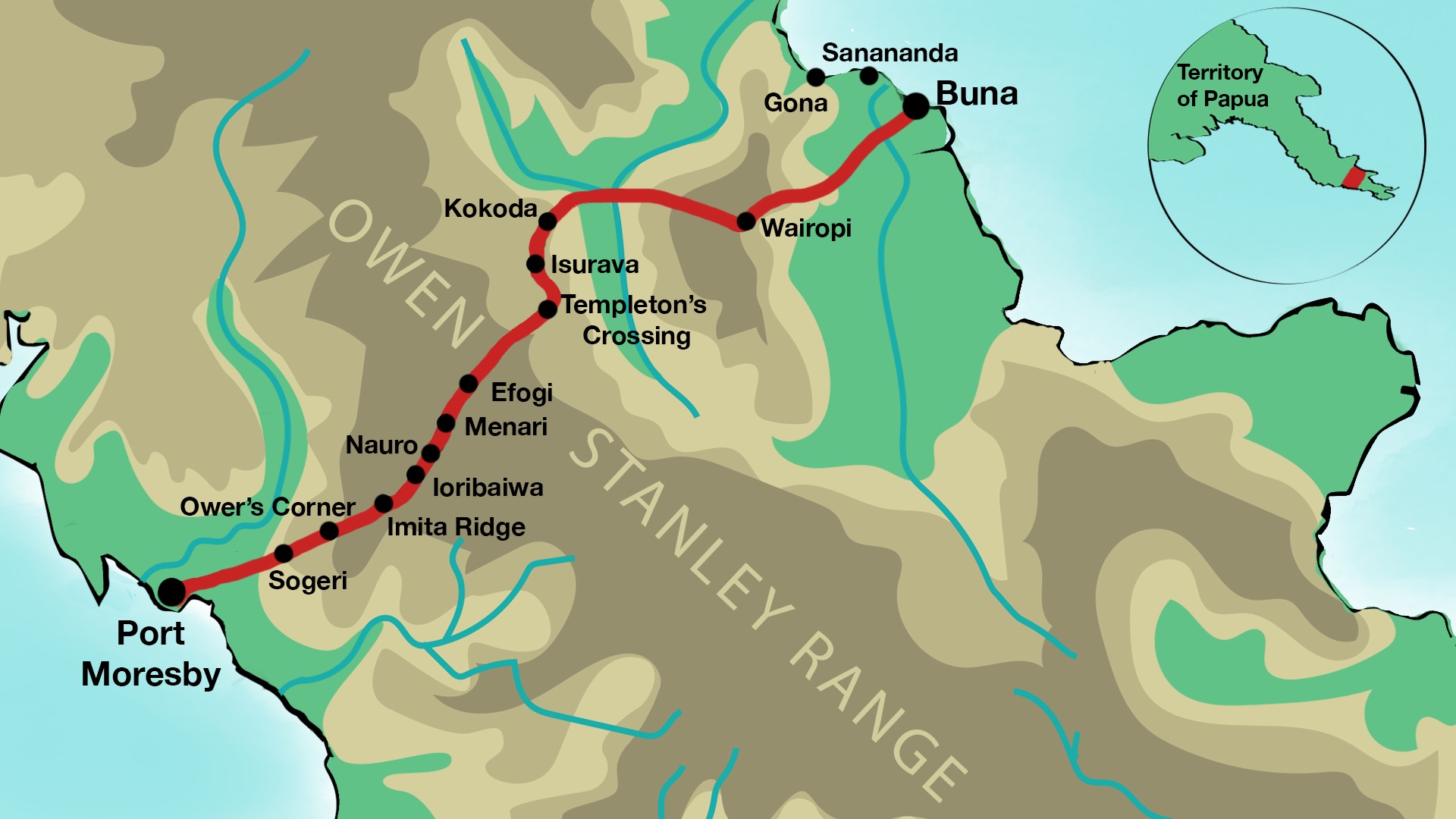

You will have read information about the Kokoda Trail campaign in the Defining Moment in Australian history: 1942 Japanese bomb Darwin but are halted on Kokoda Trail. But to understand the nature of the experience for the people involved we need to look at information from people at the time.

Look at the following evidence to help you develop more detailed knowledge and understanding of Kokoda, and also develop a greater empathetic awareness of the experience. You will also find ideas and language that are unacceptable today. The evidence has been divided into 7 themes. Explore the evidence for each theme and answer the questions that follow. You might look at all the evidence, or divide it among your class and report back on what you have discovered.

1. The environment and living conditions

1. The environment and living conditions

A journalist describes the Trail

It is full of malaria, ague, dysentery, scrub typhus, obscure diseases; full of crocodiles and snakes and bloated spiders, leeches, lice, mosquitoes, flies, all the crawling, creeping, leaping, flying biting reptiles and insects that suck human blood (and in the morning you make a habit of knocking your boots to shake the scorpions out). Its breath is poisonous; it stinks of rotten fungus and dead leaves turning softly liquid underfoot; mould and mildew put their spongy paws over everything; shoes, papers, clothing, sprout with grey beards, and there is a mottling of brown measle-spots on the cigarette which sags from your mouth, if you’ve been lucky enough to find a cigarette.

Sometimes it’s so wet that wood won’t burn until it has been dried by the little flame which you keep smouldering almost permanently, like prehistoric man. Sometimes it’s so hot that sweat trickles like brine over the lips. Sometimes it’s so cold that your bones seem to chatter. Sometime it’s so high that your ears hurt, you can’t hear properly, you have to keep opening and shutting your mouth. At the end of the trail, the Japanese with knives and bullets. But the jungle enlists a thousand enemies before this last enemy of all. It is unending, unrelenting, unforgiving. It is maleficent. It is not made for man...

Kenneth Slessor in R Gerster and P Pierce (eds), On the War-path: An Anthology of Australian Military Travel, Melbourne University Press, 2004, p. 190

Mick Considine remembers

Most times you couldn’t use your tent, you sat in a hole in the ground and tried to sleep with mud, water, maggots ...You were working hard by day, then at night you couldn’t sleep. Mosquitoes were terrible. We used to try and wrap ourselves in our one blanket, which would be wringing wet, but our feet would stick out the bottom and we had no socks. The mosquitoes would bite your feet until they were red raw.

Vicnet, New Guinea, https://web.archive.org/web/20121020151854/http://home.vicnet.net.au/~a…, viewed 12 October 2020

a) What do these sources tell you about the New Guinea and Papua environments?

b) What impacts did the environment have on the living conditions of soldiers?

2. Nature of the fighting

Retreat from Ioribaiwa

The conditions under which the Australians retreated from Kokoda beggar description. Men were so rotten with dysentery that they walked clad only in their shirts. Small parties, cut off by the Japs, made their way back through the enemy lines at night, slaying little groups of Japanese soldiers as they slept and stealing their food. Men slept in the slush and the rain, and were roused from their sleep to retreat, and fight, and retreat again ... No prisoners were taken on either side. No quarter was asked and no quarter was given. Men who were wounded were left to die on the side of the trail.

G Reading, Papuan Story, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1946, p. 50

Soldier QX12104 remembers

I will never forget my first day in action against the Japanese in New Guinea. My knees were knocking, my heart was pounding, and I was FRIGHTENED all day, and to make things worse it was raining like hell. One day we were in single file like following the leader, wading in green slush and slime. I was nearly buggered, and when I stepped over the slimy log I sunk right down to my waist in the muddy water, and the so-called log slid around under my groin. When I looked down at it a Jap skull was looking up at me, with no eyes, no nose and a hole where his mouth was. Well my hair stood straight up, and my helmet tipped over my forehead. I grabbed a prickly vine for support, and my stomach coming up to my throat, but I had to keep on walking, or I would have been lost.

J Barrett, We Were There, Viking, Melbourne, 1987, p. 67

Victor Austin remembers

After a few bursts of fire the order came to fix bayonets, and it was then, for the first time, I became really frightened. The clash in the village was short and sharp with a few killed and wounded on both sides. One Jap was lying beside the track with both legs chopped from the trunk of his body, and where his legs should have joined the trunk there was just a mass of blood – he had been cut in half by a burst of .45 ‘Tommy’ gun fire! His eyes were still open and had a terrified expression and he was moaning.

And then came the beginning of some of the terrible things that happen in combat. Our officer didn’t have the stomach to finish off the dying ‘Nip’ – instead he detailed me to do it, and I have lived to this day with those terrified eyes staring at me.

V Austin, To Kokoda and Beyond, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1988, p. 125

A war correspondent on the nature of combat

The whole battle had become a blind groping in a tangle of growth. It was seldom that anyone got a glimpse of the enemy. Most of the wounded were very indignant about it. I must have heard the remark ‘You can’t see the little bastards!’ hundreds of times in the course of a day. Some of the men said it with tears in their eyes and clenched fists. They were humiliated beyond endurance by the fact that they had been put out of action before even seeing a Japanese.

O White, Green Armour, Penguin, Melbourne, 1988, pp. 195–205

Papuan campaign deaths

Australian: 2410

American: 1435

Papuans: 40 while serving with Allies, 1200 while serving with Japanese

Japanese: 13600 (mainly at Buna-Gona-Sanananda)

Peter Williams, Kokoda for Dummies, Wiley, Richmond, 2012, pp. 200-202

a) What was the nature of the fighting on the Kokoda Trail?

b) How did Australians soldiers feel about the experience?

3. Medical and wounded

A war correspondent on the nature of combat

At Eora I saw a 20-year-old redheaded boy with shrapnel in his stomach. He kept muttering to himself about not being able to see the blasted Japs. When Eora was to be evacuated, he knew he had very little chance of being shifted back up the line. He called to me, confidentially: ‘Hey, dig, bend down a minute. Listen ... I think us blokes are going to be left when they pull out. Will you do us a favour? Scrounge us a tommy gun from somewhere, will you?’

It was not bravado. You could see that by looking in his eyes. He just wanted to see a Jap before he died. That was all. Such things should have been appalling. They were not appalling. One accepted them calmly. They were jungle war – the most merciless war of all.

O White, Green Armour, Penguin, Melbourne, 1988, pp. 195–205

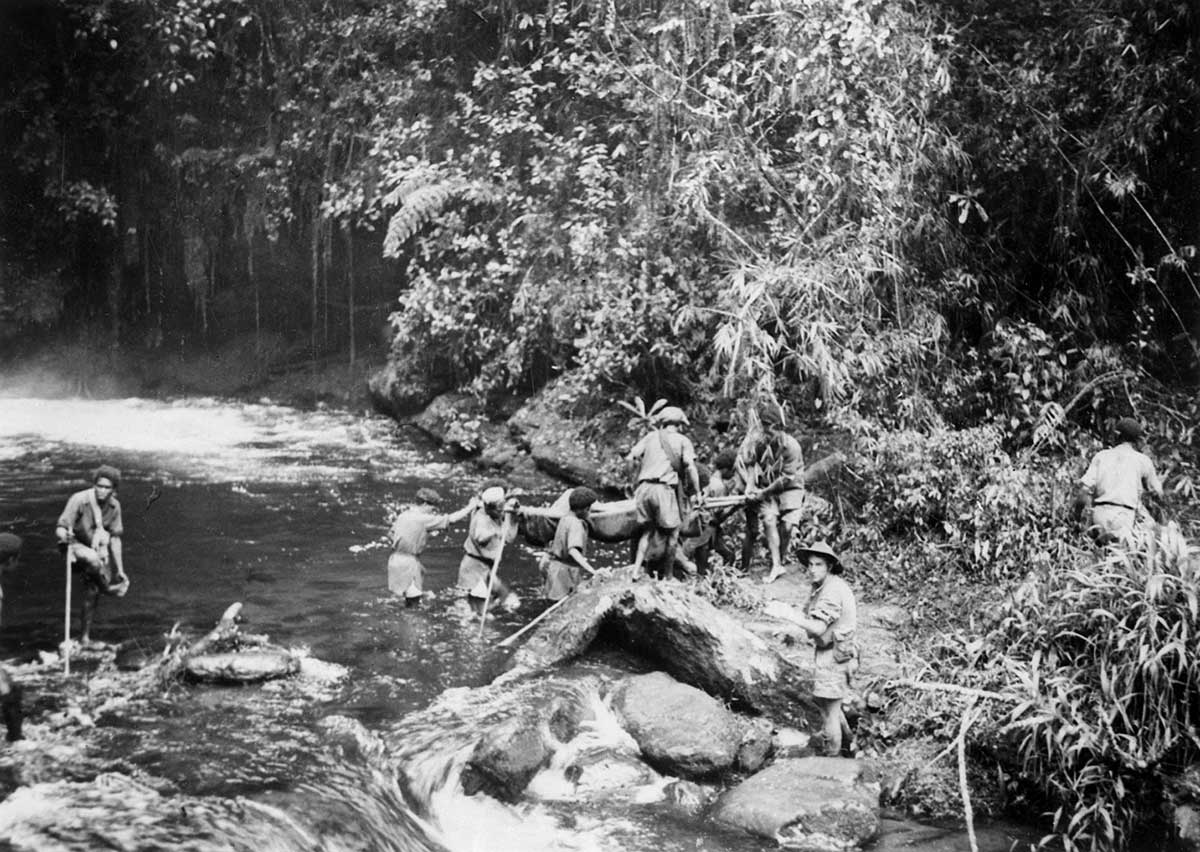

Papuan bearers

Every team of bearers was responsible for the patient, and they took pride in their sick patients and gave them every care – protecting them as far as possible from wet, and giving them drinks of water. At night the patient was made as comfortable as possible – if necessary, a shelter was built, the food provided was given to them – they themselves going without. Four natives slept on each side, and if the patient stirred or complained in the night – one native would investigate.

The carrying of the patients was one of the hardest tasks the natives were asked to do – some twelve hours per day – day after day – it took approximately ten days to carry wounded from Deniki to Base.

Papua Campaigns, ‘Report dealing with medical organisation 1942’, AWM 54 481/2/48

a) What impact did jungle warfare have on the wounded?

b) What was the main role of the Papuans and why was this important?

4. Food shortages and supplies

Jack Sim remembers

We were carrying a badly wounded mate on a stretcher and we were straggling along, see there were only seven of us and that affected the rotation, four and four.

That night we slept on the track somewhere in the jungle and I could see something glistening in the moonlight. And it was a tin of IXL blackberry jam. So we opened it up with our bayonets and scooped it out in handfuls and ate it with a biscuit. The most beautiful stuff I ever tasted in my life.

The poor bloke died that night. And although I’m ashamed to say it, in my heart and although no-one said it, we weren’t sorry.

Four Corners — The Men Who Saved Australia, ABC TV, 1988

Cannibalism

An Australian patrol found Australian bodies at Templeton’s Crossing. They were tied to trees, and pieces of their bodies cut off. Uneaten body parts were found in Japanese packs nearby.

Two Japanese diaries recorded:

‘No provisions. Some men are said to be eating the flesh of Tori [an abbreviation of Toriko, a captive] ...’

‘Because of the food shortage, some companies have been eating the flesh of Australian soldiers ... We are looking for anything edible now and are eating grass, leaves and the pith of [trees].’

In fact, a few Australian troops also succumbed to the temptation. An Australian patrol, lost and starving for weeks behind enemy lines, cannibalised one of their dead mates.

P Ham, Kokoda, ABC Books, Sydney, 2010, pp. 346–7

a) How important was the provision of food and other supplies to the soldiers who fought on the Kokoda Trail? Explain your answer.

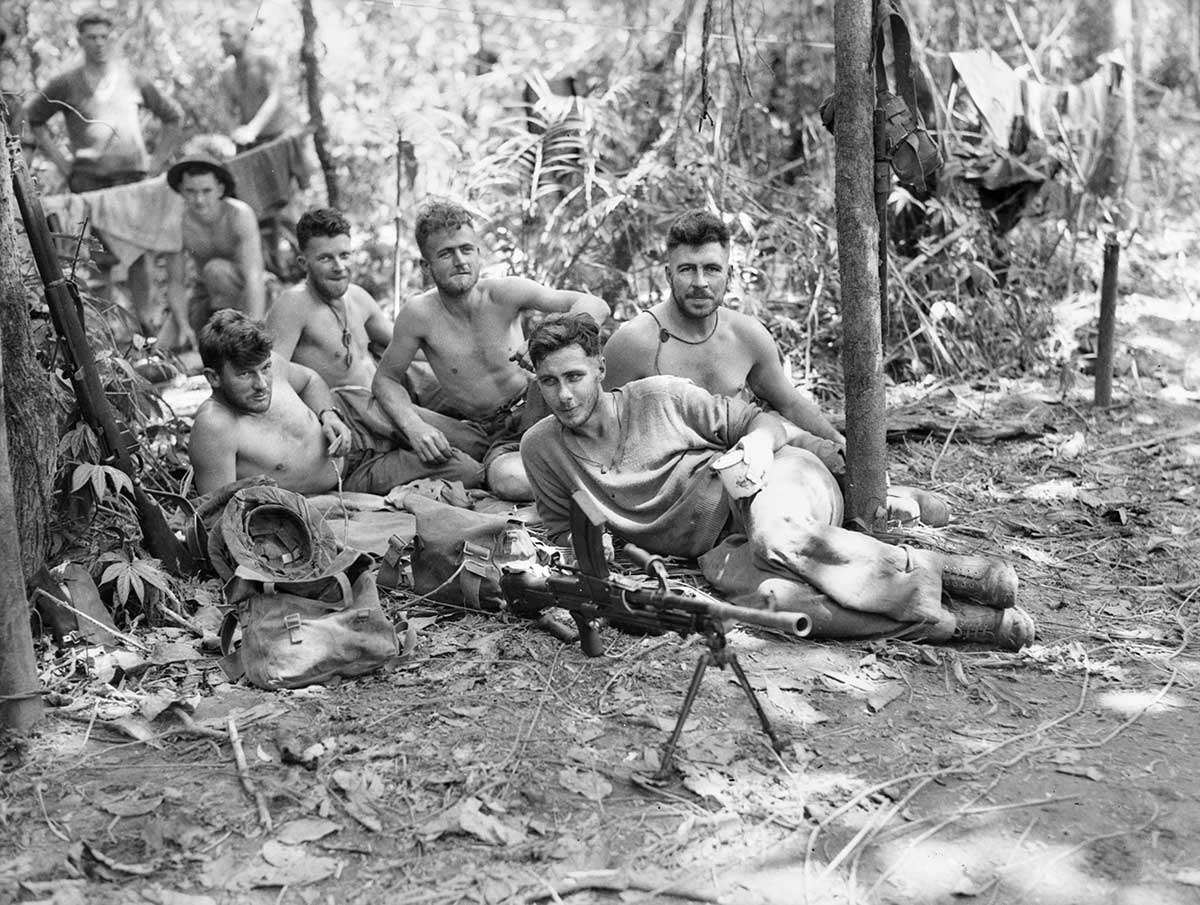

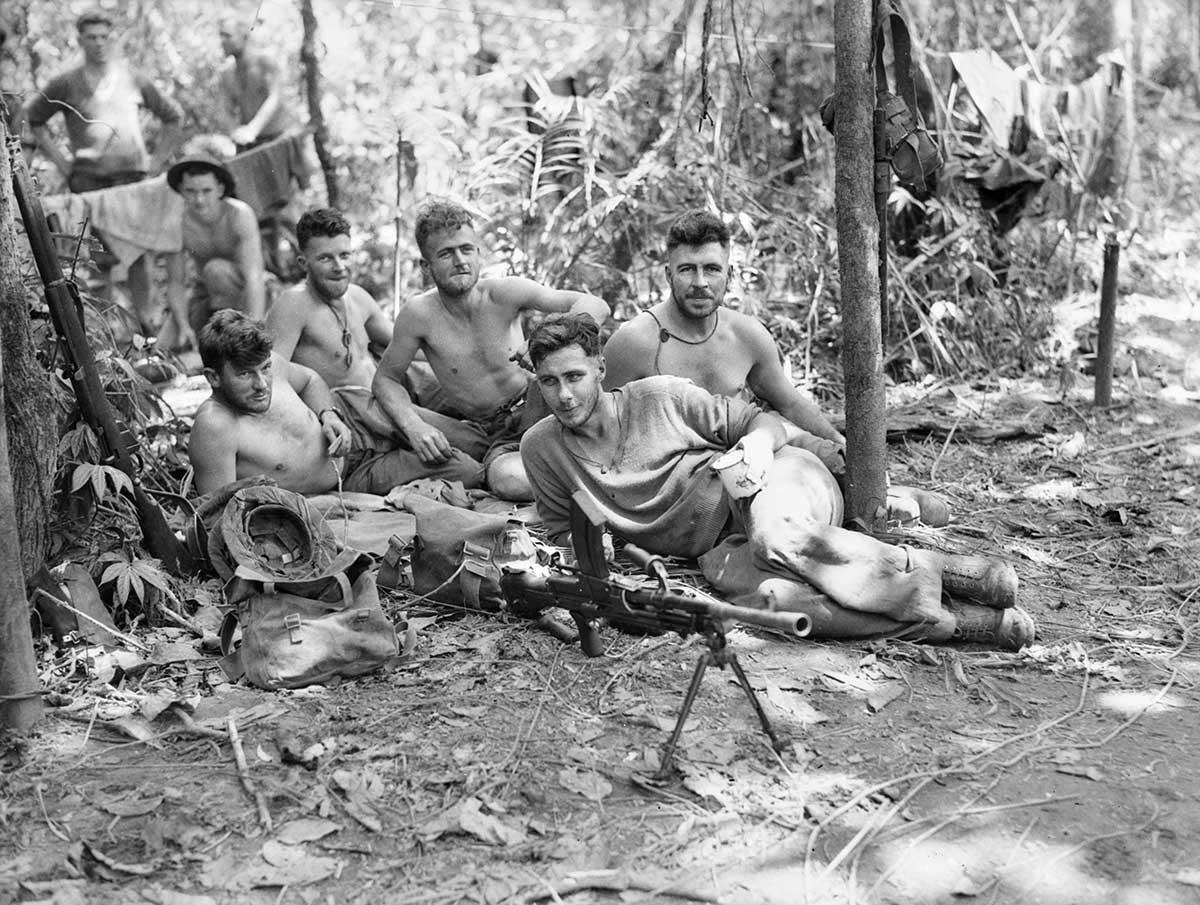

b) Compare the photograph above of soldiers resting on the Kokoda Trail with the source entitled ‘cannibalism’. How do you account for the difference between these two sources?

5. The Japanese soldiers

Jack Manol remembers

I struck this Japanese officer and he rose up from the kurnai [grass] and we were face-to-face with each other and I think he was just as bloody scared as I was, and I was just lucky that I could pull the bloody trigger first. That haunted me for years. When I went through the bloke’s equipment I found he had photographs of himself and his wife and three little kids.

Four Corners — The Men Who Saved Australia, ABC TV, 1998

The Japanese soldiers

There were sensitive natures [among the Japanese] but they had a different attitude ... They were part of a society where discipline was something so ingrained and their notion of honour as soldiers was such that they fought fanatically.

Victor Austin in P Ham, Kokoda, ABC Books, Sydney, 2010, p. 528

Extracts from Japanese soldiers’ diaries and notebooks

I am tired of NEW GUINEA, I think only of home, I wish I could eat a belly-full. I have hardly eaten for 50 days, I am bony and skinny, I walk with faltering steps, I want to see my children.

Whenever and wherever I die, I will not regret it because I have already given my soul and body to my country and I have said farewell to my parents, wife, brother and sister.

To the enemy officer: I am sorry to trouble you, but I beg you to bury my body, placing the head towards the north west. I fought bravely till the last. The situation was unfavourable to us. My end has come.

A Study of the Japanese Soldier, AWM 54 411/1/38

a) What do these sources tell you about the characteristics of Japanese soldiers?

b) How did these characteristics affect the nature of the battlefield contest?

6. The Australian soldiers

‘Throwing in the sponge’

Surprisingly few lost their minds. Mental collapse was quite rare … [there were] only a few cases during the retreat of ‘blokes throwing in the sponge’...

A few troops were accused of self-inflicted wounds ... [one medical officer claimed that] of small hand and foot wounds [that] did flow into Queensland hospitals in suspiciously large numbers ... between 10 and 25 per cent ... were intentional. There has been no investigation.

P Ham, Kokoda, ABC Books, Sydney, 2010, p. 206

Extracts from the poem Jungle Patrol by Corporal Peter Coverdale

With senses keen all nerves alert,

we move along the track,

With weapons gripped in ready hands,

all ready for the trap;

. . .

Not a word is spoken as we file along,

unbroken the jungle’s gloom.

. . .

Tensed for the impact of a shot,

from a hidden sniper’s lair.

Ready for the deadly booby traps

to take the innocents unaware.

Scanning the tops of nearby trees,

ready to clear the track

And reply with chattering Owen gun,

to the sniping rifle’s crack.

…

We fan out from the narrow trail,

leave some to watch our flank,

And sneak upon those rude grass huts,

through jungle green and dank.

We work in pairs from hut to hut,

find trace of recent foe.

Black fires still warm, and half cooked rice,

on cautious way we go.

A sudden roar as a lone sick Jap,

holds grenade against his chest,

thinking he’ll take us with him too,

to that heathen warrior’s rest.

No wonder we’re callous, hard at heart,

no pity for the wounded Jap.

Many a brave Australian life,

was taken by the same trap.

Corporal Peter Coverdale, ‘Jungle Patrol’, All Poetry, https://allpoetry.com/Jungle-Patrol

Heroism at Isurava

The Australians had neither the numbers nor the ammunition to withstand the onslaught. They were gradually overwhelmed, but not without a string of extraordinary last stands, which yielded more Allied decorations than in any other single battle in the Pacific.

These were not blind heroics; they were calculated initiatives by Australian privates, corporals and platoon commanders determined to hold off the enemy as their units withdrew. Thus Private Wakefield, a Sydney wool worker, held up a Japanese charge as his section fell back; he won the Military Medal. Thus Captain Maurice Treacy, a shop assistant, ‘parried every thrust levelled at him’. He got a Military Cross. Though wounded in the hand and foot, Corporal ‘Teddy’ Bear, a die-cast operator from Moonee Ponds, killed a reported 15 Japanese with his Bren gun at point blank range; he was later awarded the Military Medal and the DCM. Lieutenant Mason, a draftsman, led his platoon in four counterattacks that afternoon; as did Lieutenant Butch Bissett, a jackaroo, whose platoon fought off fourteen Japanese charges.

P Ham, Kokoda, ABC Books, Sydney, 2010, pp. 175–7

a) What do these sources tell you about the characteristics of Australian soldiers?

b) Do you think these characteristics were important to the eventual outcome of the fighting?

7. Strategic importance of the Kokoda Trail

Jack Manol remembers

Oh my God, that walking! The first half hour I thought, ‘No, I’ll never do this. ‘I was exhausted! But I didn’t like to show it, to anyone, particularly to the country blokes, because they were going along all right.

At one stage I remember looking around at my few mates in the section and they’re yellow skinned and a dirty, scruffy lot and I thought: ‘Christ, there’s no-one between us and Moresby, and if the Japs get through us and get to Moresby there, Australia’s gone’.

Four Corners — The Men Who Saved Australia, ABC TV, 1998

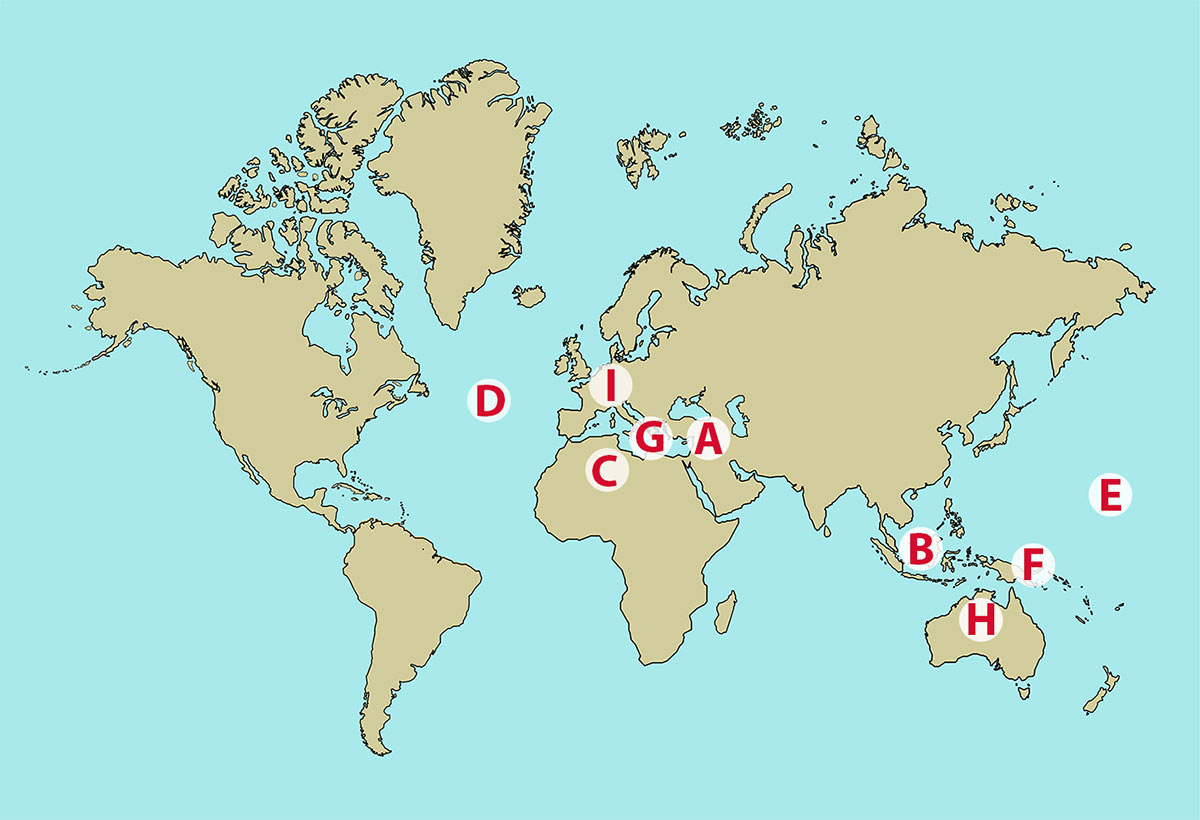

a) Where is Papua located in relation to Australia?

b) Do you agree that the Kokoda Trail was of strategic importance to Australia? Explain your answer.

Conclusion

8. Overall, what was the experience of Australian soldiers on the Kokoda Trail and how did this experience affect the soldiers who fought there?