Rights and freedoms Defining Moments, 1945–present

- Year level 10

- Investigations 1

- Activities 30

- Curriculum topic Rights and freedoms

1. Overview of the learning module

Introduction

This learning module provides resources and classroom activities for teachers to use in their Australian Curriculum: Humanities and Social Sciences year 10 classrooms.

It supports the History knowledge and understanding strand, Depth Study 2, Rights and Freedoms (1945–the present).

The learning module focuses on starting points for investigating the key inquiry question in the history element of the curriculum:

- How was Australian society affected by other significant global events and changes in this period?

The learning module is self-contained, and can be used in any of the following ways:

- as whole class activities with all students studying a number of Defining Moments in Australian History that help them understand aspects of Australia’s history

- distributed between small groups, with students reporting back on their findings to the whole class

- as selected enrichment activities for individual students.

The module’s single investigation provides a rich digital resource for classroom use. It includes contextual information, documents, images, scaffolded comprehension, analytical and extension questions, and individual, group and class activities. Using these materials and activities, students can explore aspects of twentieth century Australian history through text, images and objects.

The learning module has been designed to draw on the National Museum of Australia’s Defining Moments in Australian History, together with some supplementary resources.

What constitutes a defining moment in Australian history, and why some issues and situations can be considered more significant than others, is an underlying theme that can be raised with students throughout the module.

Module snapshot

The learning module can be used to create a set of preliminary ideas, understandings and questions that will help students investigate the topic in more detail.

It contains:

- Setting the scene

All students engage in the introductory ‘tuning in’ activity. This activity helps students understand the concept of loss of rights — citizenship rights, land rights and cultural rights (or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights).

- Investigation 1.1–1.28

Students are set the task of examining 27 Defining Moments and deciding which of these have been the most important in helping to achieve lasting change in the development of Indigenous rights in Australia.

To make the task more manageable, teachers can divide the 27 Defining Moments amongst the class and then have each group report their findings to each other.

There is a summary table to aid with the classroom discussion. The discussion could cover areas such as:

- What have been the most significant ways in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s rights in Australia have changed over time?

- What have been the most powerful influences in achieving those changes?

- Why have some rights been resisted?

- Do Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a right to sovereignty and self-determination, or are these exclusive to the Australian nation as a whole?

After students have examined and discussed all 27 events and chosen the events they think were most important, they can discuss their ideas with classmates and create a ‘whole class list’ of the 5–10 most important Indigenous rights Defining Moments.

Finally students decide as a class which 2–3 current Indigenous rights issues might become the next Indigenous rights Defining Moments, justifying your choices.

- Bringing it together

Reflections and class discussion

Students will consider which of these events have been the most influential in improving the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and whether there are rights that still need to be achieved.Quiz

When students have finished they take part in a quiz to test their understanding of all the events on the journey.

2. Student activities

Student activities

3. Relevant Defining Moments in Australian History

The learning module draws on the resources on the Defining Moments in Australian History website, together with supplementary materials.

Defining Moments that are relevant to the inquiry questions in the curriculum include:

Simplified versions of many of the relevant Defining Moments are also available:

4. Australian Curriculum level and focus

Historical knowledge and understanding

Students will cover the following areas:

- The origins and significance of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including Australia’s involvement in the development of the declaration (ACDSEH023)

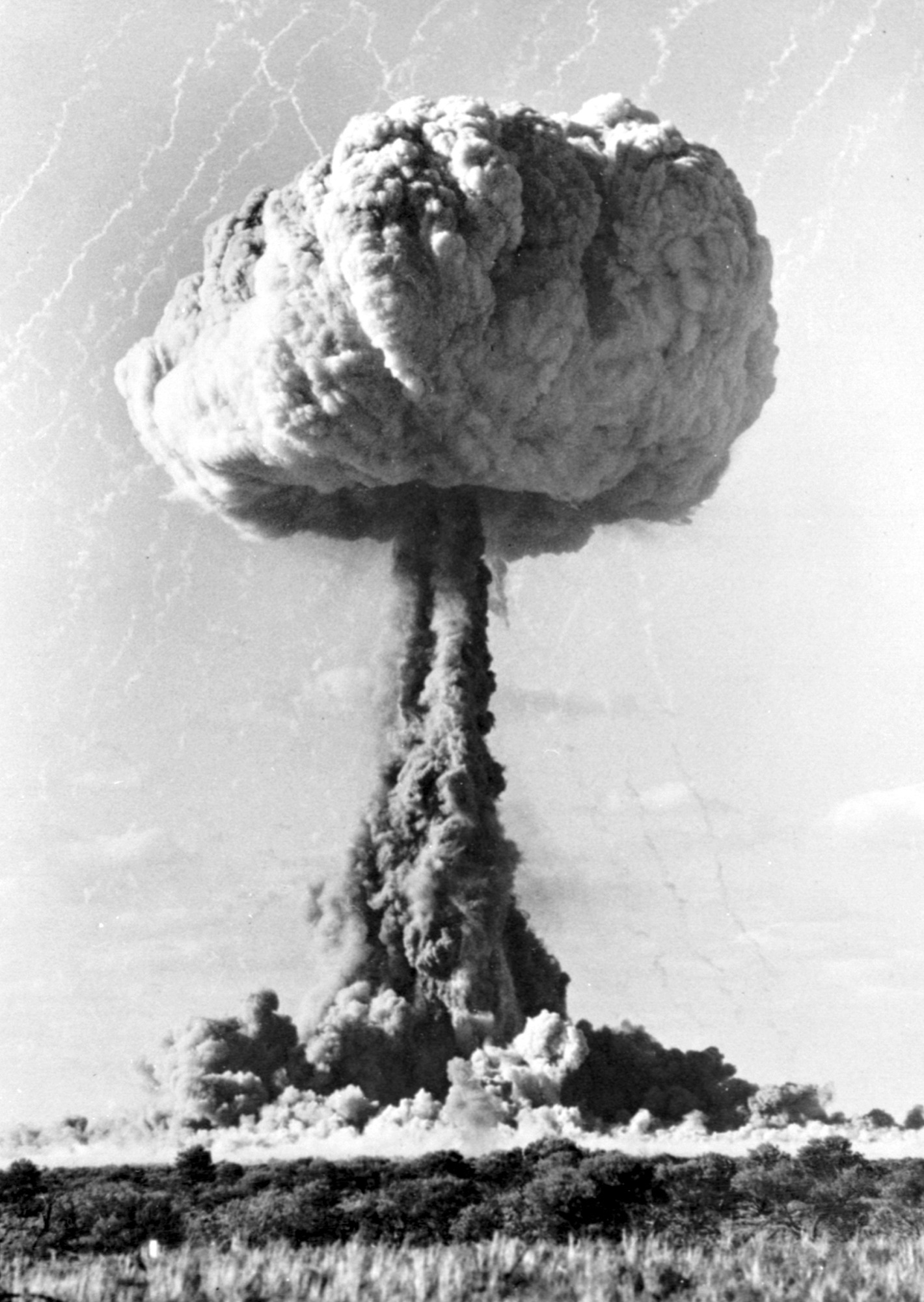

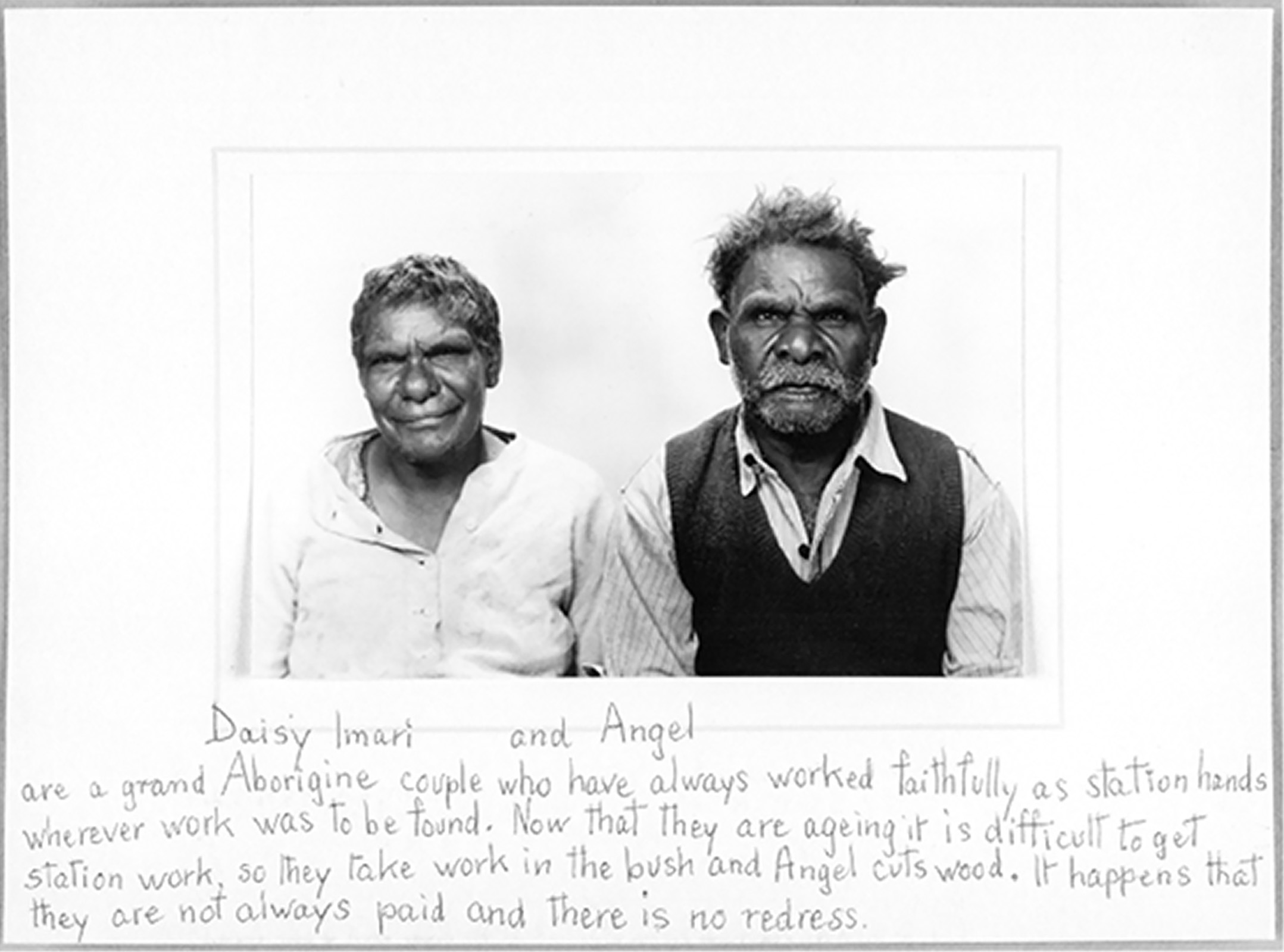

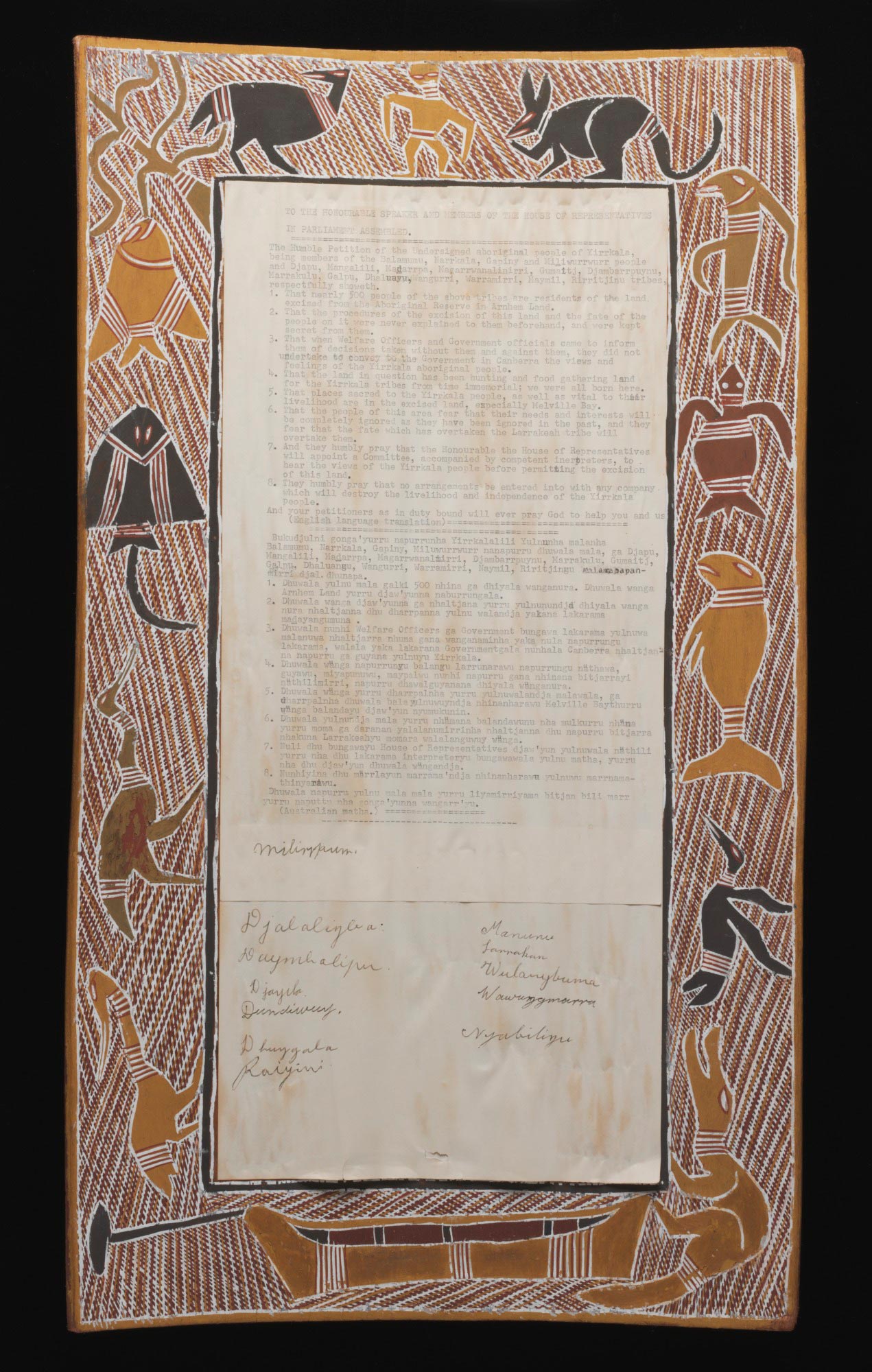

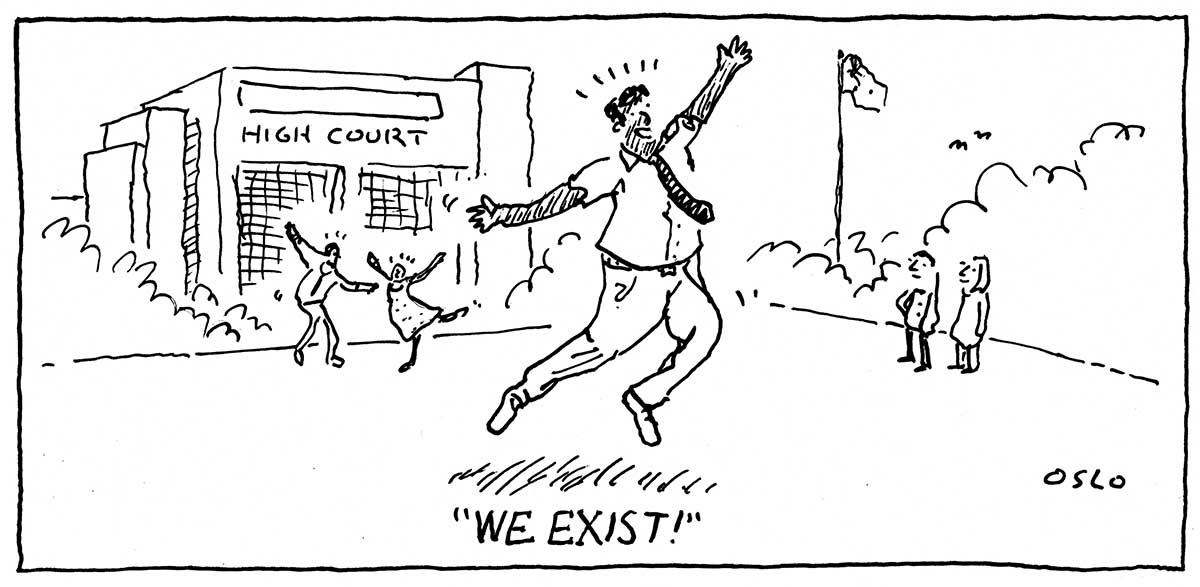

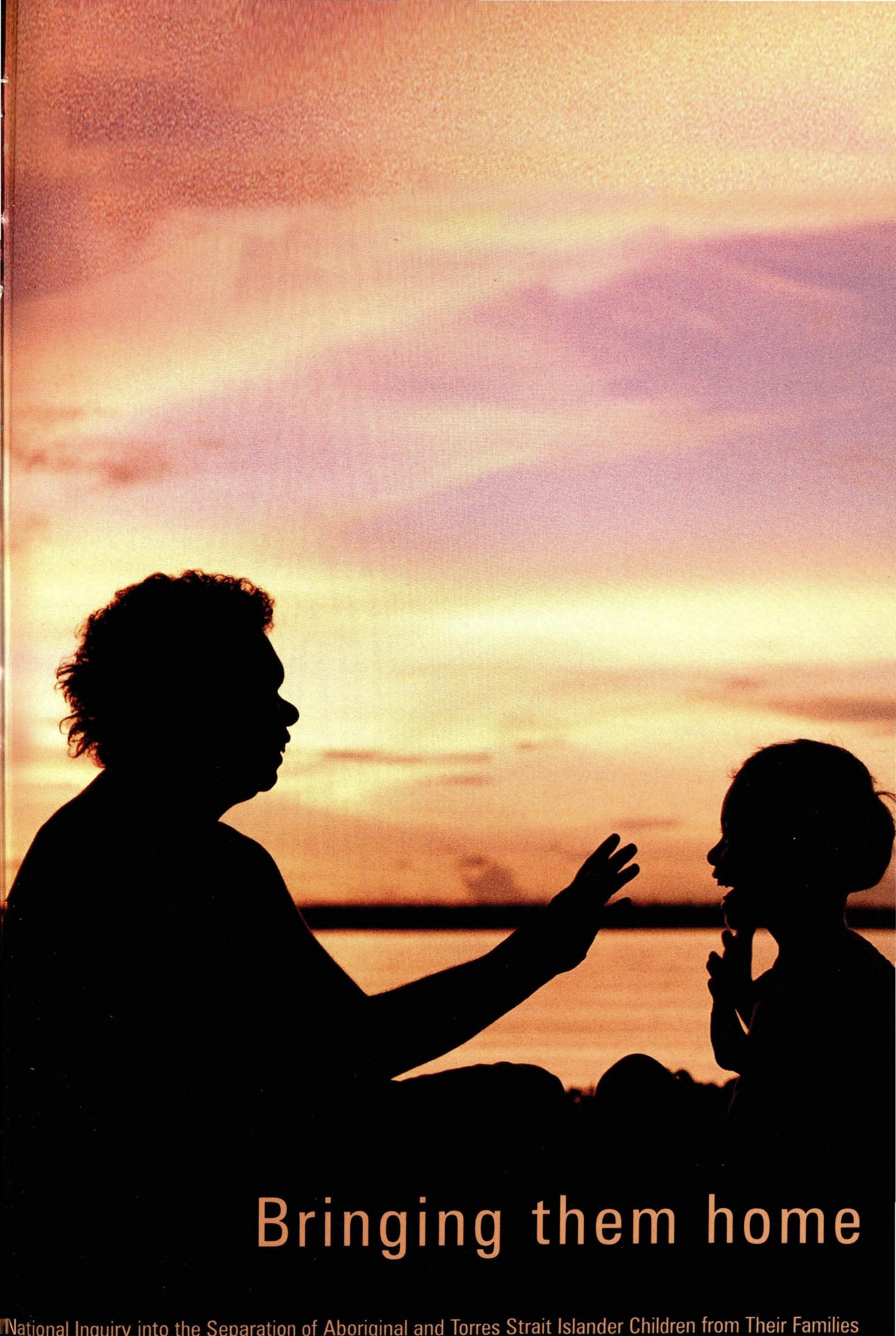

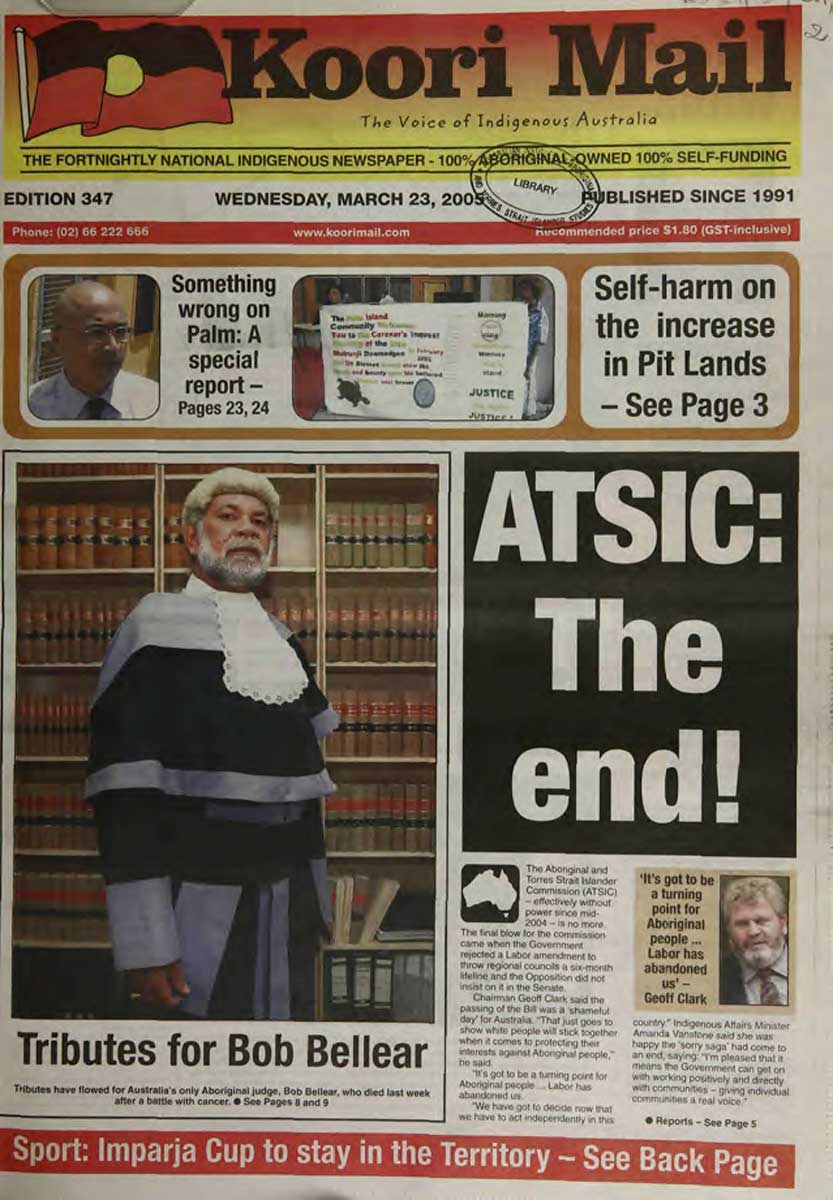

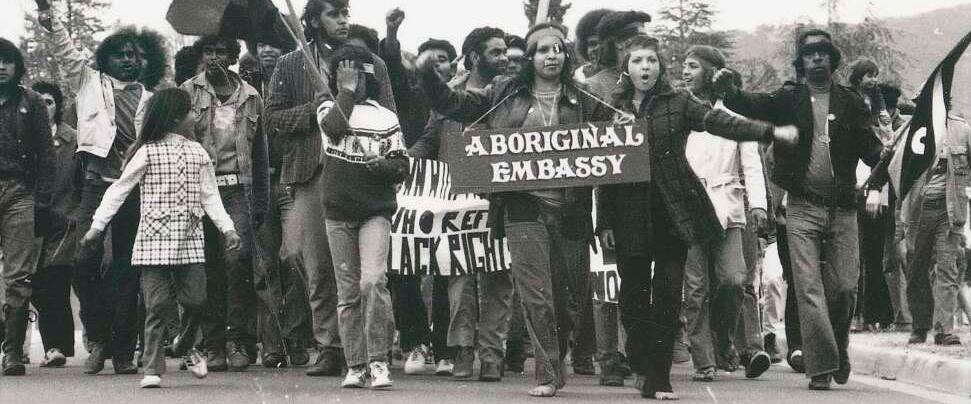

- Background to the struggle of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples for rights and freedoms before 1965, including the 1938 Day of Mourning and the Stolen Generations (ACDSEH104)

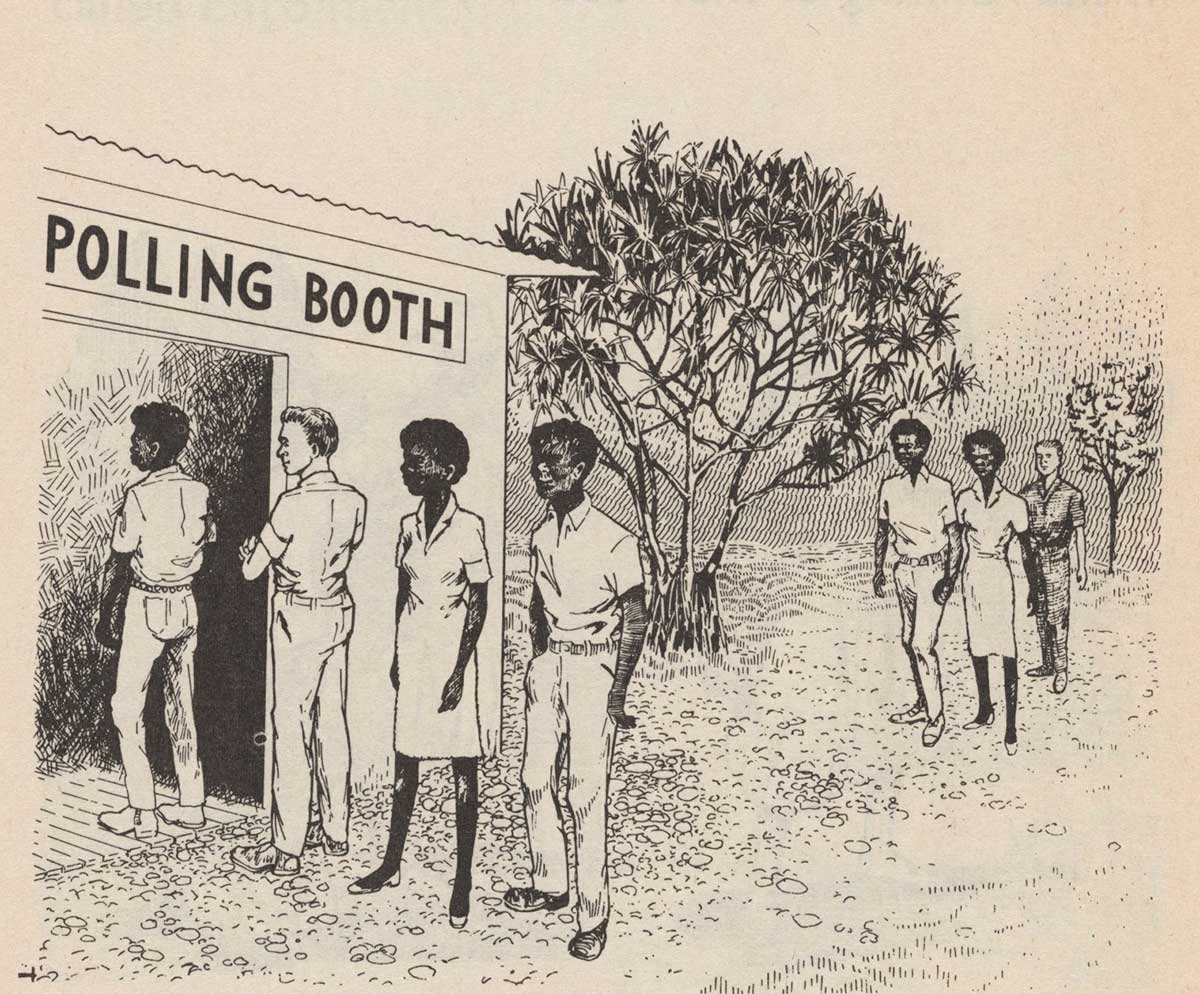

- The significance of the following for the civil rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: 1962 right to vote federally; 1967 Referendum; Reconciliation; Mabo decision; Bringing Them Home Report (the Stolen Generations), the Apology (ACDSEH104)

- Methods used by civil rights activists to achieve change for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, and the role of ONE individual or group in the struggle (ACDSEH134)

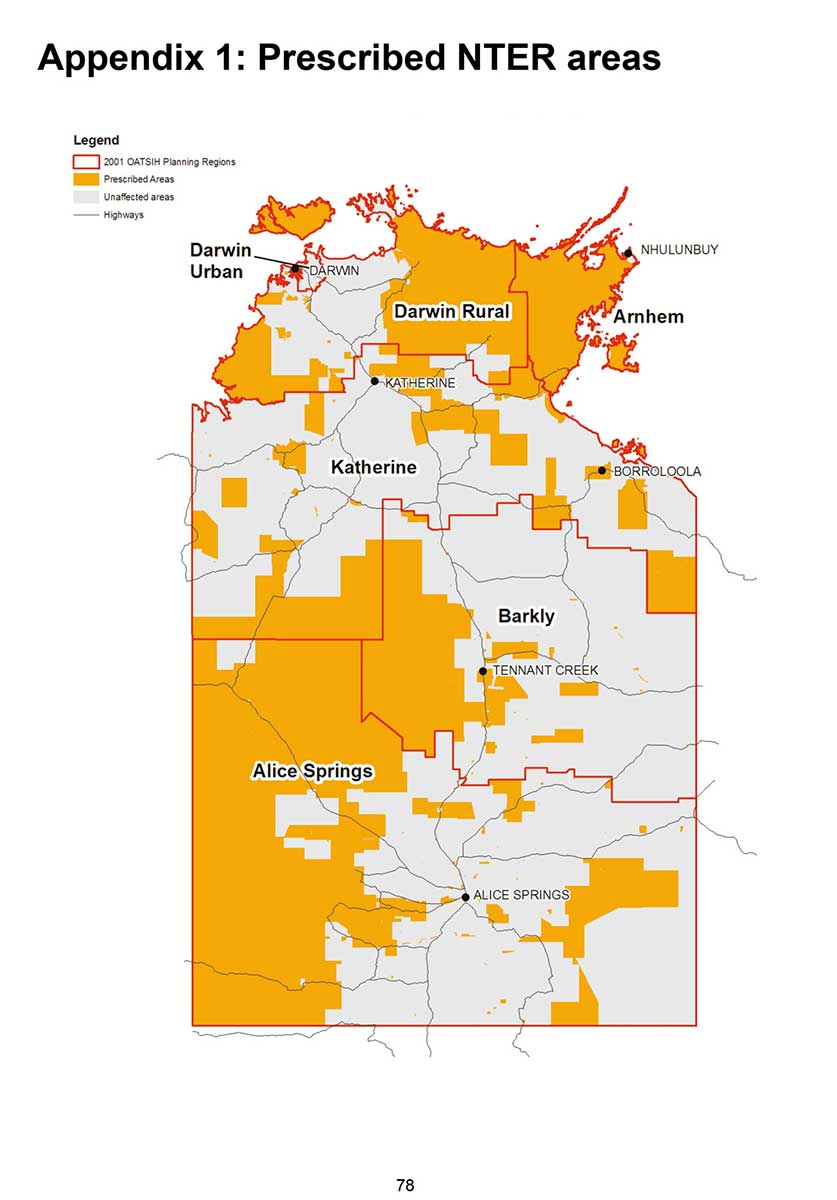

- The continuing nature of efforts to secure civil rights and freedoms in Australia and throughout the world, such as the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) (ACDSEH143)

Historical skills

Students will exercise the following historical skills:Chronology, terms and concepts

- Use chronological sequencing to demonstrate the relationship between events and developments in different periods and places (ACHHS182)

- Use historical terms and concepts (ACHHS183)

Historical questions and research

- Identify and select different kinds of questions about the past to inform historical inquiry (ACHHS184)

- Evaluate and enhance these questions (ACHHS185)

- Identify and locate relevant sources, using ICT and other methods (ACHHS186)

Analysis and use of sources

- Identify the origin, purpose and context of primary and secondary sources (ACHHS187)

- Process and synthesise information from a range of sources for use as evidence in an historical argument (ACHHS188)

- Evaluate the reliability and usefulness of primary and secondary sources (ACHHS189)

Perspectives and interpretations

- Identify and analyse the perspectives of people from the past (ACHHS190)

- Identify and analyse different historical interpretations (including their own) (ACHHS191)

Explanation and communication

- Develop texts, particularly descriptions and discussions that use evidence from a range of sources that are referenced (ACHHS192)

- Select and use a range of communication forms (oral, graphic, written) and digital technologies (ACHHS193)

Interdisciplinary thinking

Students will have engaged with the concepts of:

- significance

- continuity and change

- cause and effect

- place and space

- interconnections

- roles, rights and responsibilities

- perspectives and action.

Cross-curriculum priorities

Students will have been involved in additional learning about aspects of:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies

- Asia and the Pacific

- sustainability

Source: The Australian Curriculum Humanities and Social Sciences, v8.3, December 2016, accessed 1 November 2018

5. History outcomes matrix

All case studies in the learning module have been designed to help students develop the knowledge and skills outcomes specified in the Australian Curriculum — History. At the end of each case study teachers could use this matrix to help guide student discussion about what they have achieved from the case study. The matrix is suitable to be used from Years 5–10, but with teachers guiding the discussion as appropriate to the particular class. It could also be used for assessment purposes.

|

Outcome |

Elaboration or explanation |

Applying this to each case study |

|---|---|---|

|

KNOWLEDGE |

Comprehending what happened factually. |

What happened? |

|

UNDERSTANDING |

Being able to explain what happened and why. |

Explain why it happened. |

|

CHRONOLOGY |

Knowing how events occurred in time and place. |

Explain how events unfolded. |

|

CAUSE AND EFFECT |

Understanding why events occurred as they did and the impacts or effects they had. |

Explain the causes of the event and its impacts. |

|

EMPATHY |

Looking at events from the different perspective of participants. |

Why do you think people at the time might have behaved in this way? |

|

CHANGE AND CONTINUITY |

What changed and what remained the same after the event. |

Explain how the event changed some aspects, but not others. |

|

VOICE OR AGENCY |

Understanding whose voice or perspective is included and excluded in the record of the event. |

Which people or groups involved in, or affected by, the event have been represented? Which groups have not yet been represented? |

|

JUDGEMENT |

Deciding on the benefit or harm created by the event. |

Explain why you think the event was beneficial or harmful, or both. |

|

SIGNIFICANCE |

Explaining why it might be considered a ‘Defining Moment’ in Australian history. |

Do you think it was a significant and impactful event? Explain why you do or do not think this event is significant to Australian history. |

6. History source analysis guide

Some of the case studies involve students using historical skills to evaluate primary sources of evidence. This process involves identifying ‘bias’ but also many other features of the evidence. Students can use a source analysis guide to help them interrogate sources.

|

Aspects |

Elaborations |

Analysis

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Document |

Image |

Artefact |

||

|

DESCRIPTION |

How would you describe or classify it? What type of evidence is it? |

e.g. an official government report, a diary entry, transcript of an interview recorded 40 years after the event |

e.g. a photograph from the time, a propaganda poster, a satirical cartoon |

e.g. a made object |

|

ORIGIN |

Who created it? When? Where? |

e.g. an eyewitness account from a participant on one side, a family story handed down for generations, a newspaper report that quotes several participants |

e.g. an eyewitness, a government body, a newspaper cartoonist |

e.g. created at the time, used at the time, technique used, materials used, made by all or specialised skills |

|

CONTEXT |

What were the conditions at the time? How could they have influenced its creation? |

e.g. created during a period of crisis, created years later after the events had finished |

e.g. created during a period of crisis, created years later after the events had finished |

e.g. typical of the time or an innovation, specialised or mass production |

|

AUDIENCE |

Who was it created for? How widespread would it have been? |

e.g. a political party, a mass protest, an official inquiry, a personal record |

e.g. a political party, a mass protest, an official inquiry, a personal record, a readership |

e.g. elite people or ordinary people |

|

PURPOSE |

Why was it created? What is its style or tone? |

e.g. as an official record, to influence people to join a political party, to criticise somebody |

e.g. to entertain, to persuade or influence, to criticise, to reveal information, to record facts |

e.g. everyday use or specialised use, domestic use or trade |

|

RELEVANCE |

What does it help you know and understand about what you are investigating? |

e.g. people involved, places, times, attitudes, values of the time, supporters and opponents |

e.g. people involved, places, times, attitudes, values of the time, supporters and opponents |

e.g. work, leisure, education, attitudes, values, everyday life, food |

|

RELIABILITY |

What is its authority, accuracy and believability? |

e.g. factual accuracy, person in a position to know, first-hand or second-hand |

e.g. factual accuracy, person in a position to know, first-hand or second-hand |

e.g. typical or unusual, how closely associated with the events |

7. Learning at the National Museum of Australia

Enjoying our online teaching resources? Why not check out what else we have to offer?

We run onsite school programs, digital excursions and teacher professional learning programs.

Discover more about defining moments in Australian history through these curriculum-linked learning activities.